Bibliography

Agøy, Berit Hager, ‘The Freedom Struggle in South Africa’, in Norway and National Liberation in Southern Africa, ed. by Tore Linné Eriksen (Uppsala: Nordic Institute of African Studies, 2000), pp. 271-331

Alphen, Ernst van, Productive Archiving: Artistic Strategies, Future Memories, and Fluid Identities (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2023)

Andresen, Trond, and Steinar Sætervadet, Fra dugnad til bistand: Namibiaforeningen gjennom 20 år (Elverum: Namibiaforeningen, 2000)

Baer, Elizabeth Roberts, The Genocidal Gaze: From German Southwest Africa to the Third Reich (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2017)

Baird, Robert P., and Noel Ignatiev, ‘The Invention of Whiteness: The Long History of a Dangerous Idea’, The Guardian, 20 April 2021 <https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/apr/20/the-invention-of-whiteness-long-history-dangerous-idea> [Accessed 27 September 2024]

Bakkevig, Trond, The Church of Norway and the Struggle against Apartheid (Oslo: Church of Norway Council on Ecumenical and International Relations, 1996)

Beukes, Hans, Long Road to Liberation: An Exiled Namibian Activist’s Perspective (Pinegowrie: Porcupine Press, 2014)

Birkeli, Emil, En ørkenvandrer: Norges første Afrikamissionær, H. C. Knudsen (Oslo: Lutherstiftelsen, 1925)

Biwa, Memory, ‘Weaving the Past with Threads of Memory: Narratives and Commemorations of the Colonial War in Southern Namibia’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of the Western Cape, 2012)

Bridle, James, The New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future (London: Verso, 2018)

Césaire, Aimé, Discourse on Colonialism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000)

Dreissler, Heinrich, Die Rheinische Mission in Südwestafrika, Vol. 2 (Bertelsmann, 1932)

Drolsum, Nina, ‘The Norwegian Council for Southern Africa’, in Norway and National Liberation in Southern Africa, ed. by Tore Linné Eriksen (Uppsala: Nordic Institute of African Studies, 2000), pp. 216-70

Eriksen, Tore Linné, ed., Norway and National Liberation in Southern Africa (Uppsala: Nordic Institute of African Studies, 2000)

Garten, Janet, ‘Introduction’, in Peer Gynt & Brand (London: Penguin, 2016)

Gensichen, Hans Werner, ‘Fabri, Friedrich’, in Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions (New York: Macmillan Reference, 1998)

Hartman, Saidiya, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2021)

Hartman, Saidiya, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997)

Horelli, Laura, and Heidi Brunnschweiler, eds., Changes in Direction – A Journal (Berlin: Archive Books, 2021)

Hunt-Hendrix, Leah, and Astra Taylor, Solidarity: The Past, Present, and Future of a World-Changing Idea (London: Verso Books, 2023)

Jen, Gish, Tiger Writing: Art, Culture, and the Interdependent Self (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2013)

Jørgensen, Torstein, Contact and Conflict: Norwegian Missionaries, the Zulu Kingdom, and the Gospel, 1850-1873 (Oslo: Solum Forlag, 1990)

Katjavivi, Peter H., A History of Resistance in Namibia (Woodbridge: James Currey, 1988)

Katjivena, Uazuvara Ewald Kapombo, Mama Penee: Transcending the Genocide (Windhoek: UNAM Press, University of Namibia, 2020)

Khalili, Bouchra, The Tempest Society, ed. by Gavin Everall (London: Book Works, 2018)

Kincaid, Jamaica, ‘In History’, Callaloo, vol. 20, 1 (1997), 1-7

King, Thomas, The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative (Ontario: House of Anansi Press, 2003)

Lau, Brigitte, Namibia in Jonker Afrikaner’s Time, 2 ed. (Windhoek: National Archives of Namibia, 1987)

Leys, Colin, and Susan Brown, Histories of Namibia: Living Through the Liberation Struggle. Life Histories Told to Colin Leys and Susan Brown (London: Merlin Press, 2005)

Lindqvist, Sven, Exterminate All the Brutes, trans. by Joan Tate (New York: New Press, 1996)

Madley, Benjamin, ‘From Africa to Auschwitz: How German South West Africa Incubated Ideas and Methods Adopted and Developed by the Nazis in Eastern Europe’, European History Quarterly vol. 35 (2005), 429-64

Melber, Henning, Understanding Namibia: The Trials of Independence (London: Hurst, 2014)

Miescher, Giorgio, et al., eds., Posters in Action: Visuality in the Making of an African Nation (Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien, 2009)

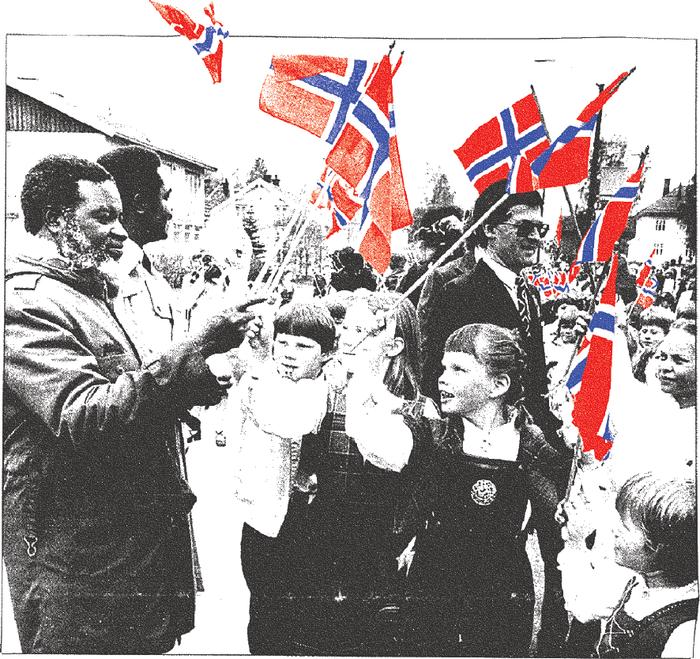

Nilsen, Kristen Nilsen, ‘Namibias statsoverhode var “boy” hos Marit Johannessen for 54 år siden’, Aftenposten, 3 November 1993, p. 1

Nujoma, Sam, Where Others Wavered: The Autobiography of Sam Nujoma (Bedford: Panaf Books, 2001)

Øieren, Oddvar, Svart på hvit: et spill om Namibias historie (Elverum: Namibiaforeningen, 1982)

Okri, Ben, Biko and the Tough Alchemy of Africa, 13th Steve Biko Memorial Lecture (Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2012) <https://www.news.uct.ac.za/images/archive/releases/2012/Ben_Okri_transcript.pdf> [Accessed 1 October 2024]

Olusoga, David, and Casper W. Erichsen, The Kaiser’s Holocaust: Germany’s Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism (London: Faber & Faber, 2011)

Østbye, Eva Helene, ‘The Namibian Liberation Struggle: Direct Norwegian Support to SWAPO’, in Norway and National Liberation in Southern Africa, ed. by Tore Linné Eriksen (Uppsala: Nordic Institute of African Studies, 2000), pp. 88-130

Østbye, Eva Helene, ‘Pioneering Local Activism: The Namibia Association of Norway’, in Norway and National Liberation in Southern Africa, ed. by Tore Linné Eriksen (Uppsala: Nordic Institute of African Studies, 2000), pp. 353-72

Price, Richard, The Convict and the Colonel: A Story of Colonialism and Resistance in the Caribbean (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006)

Salesses, Matthew, Craft in the Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing and Workshopping (Berkeley: Catapult, 2021)

Sandvik, Pål Thonstad, and Espen Storli, Controlling Unilever: Whale Oil, Margarine and Norwegian Economic Nationalism, 1930-31, conference paper, 2010

Thompson, Odvar, ‘Friheten Hovedsaken’, Østlendingen, 18 May 1983, p. 1

Tjomsland, Audun, Anders Jahre: hans liv og virksomhet (Sandefjord: Tjomsland Media, 2013)

Tønnessen, Johan Nicolay, and Arne Odd Johnsen, The History of Modern Whaling, trans. by R. I. Christophersen (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982)

Trewhela, Paul, Inside Quatro: Uncovering the Exile History of the ANC and SWAPO (Johannesburg: Jacana Media, 2009)

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 2015)

United Nations Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent, End of Mission and Statement by the United Nations Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent Following its Country Visit to Norway (11-20 December 2023), Containing Its Preliminary Findings and Recommendations (United Nations Regional Information Centre for Western Europe, 2023) <https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/issues/racism/wgeapd/statements/20240312-eom-stm-wgepad.pdf> [Accessed 27 September 2024]

van der Hoog, Tycho, ‘A New Chapter in Namibian History: Reflections on Archival Research’, History in Africa (2022), 1-26 <https://www.ascleiden.nl/news/new-chapter-namibian-history-reflections-archival-research> [Accessed 1 October 2024]

van der Hoog, Tycho, and Bernard C. Moore, ‘Paper, Pixels, or Plane Tickets? Multi-archival Perspectives on the Decolonisation of Namibia’, Journal of Namibian Studies, 32 (2022), 77-106 <https://namibian-studies.com/index.php/JNS/article/view/252/252> [Accessed 1 October 2024]

Wilson, Shawn, Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods (Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 2008)