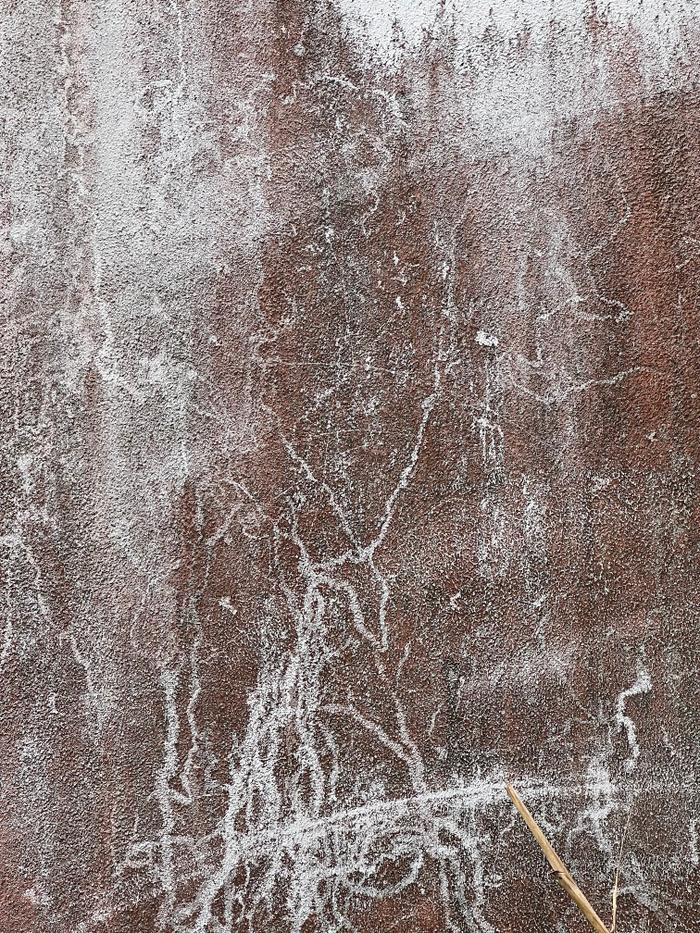

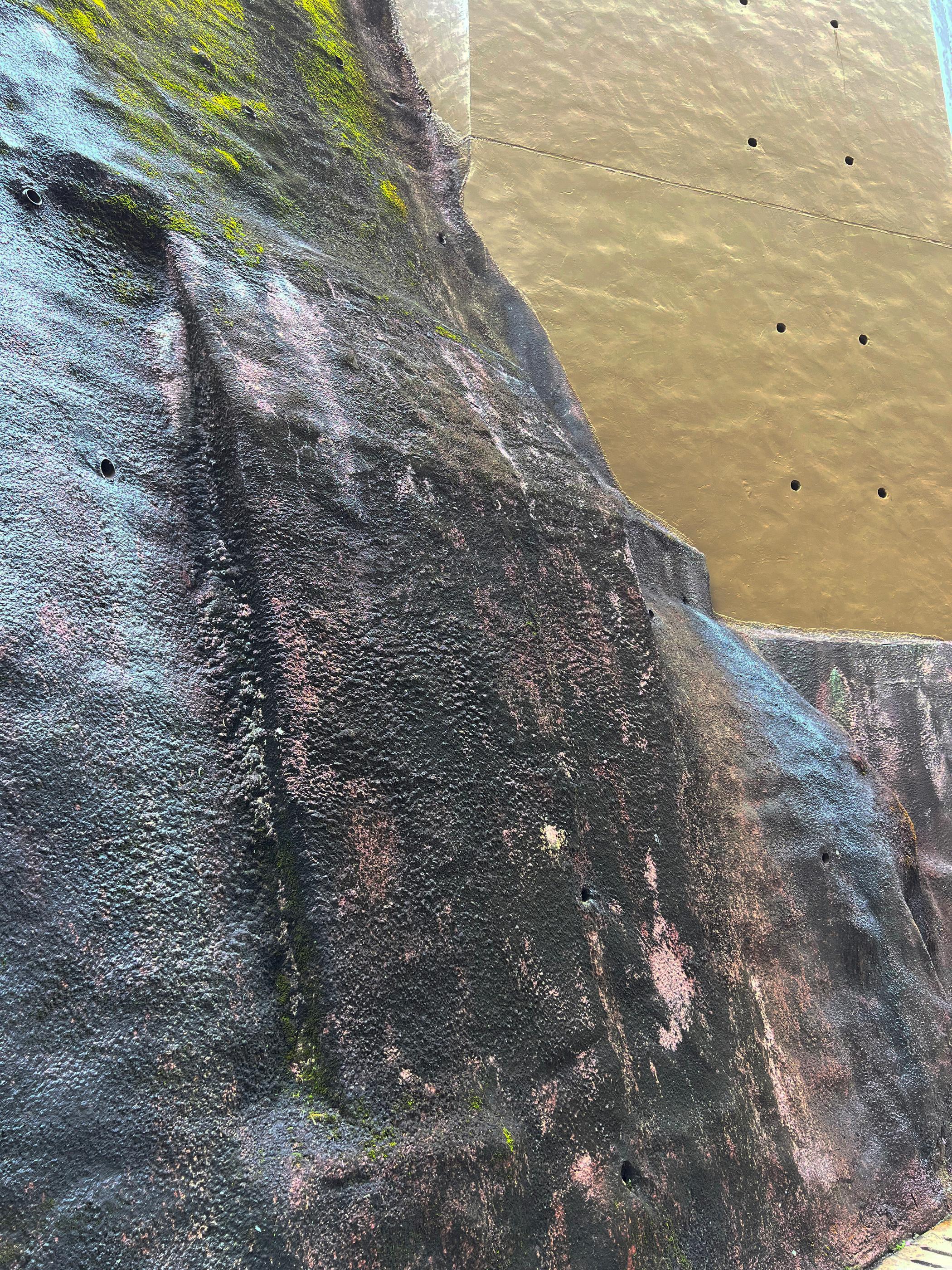

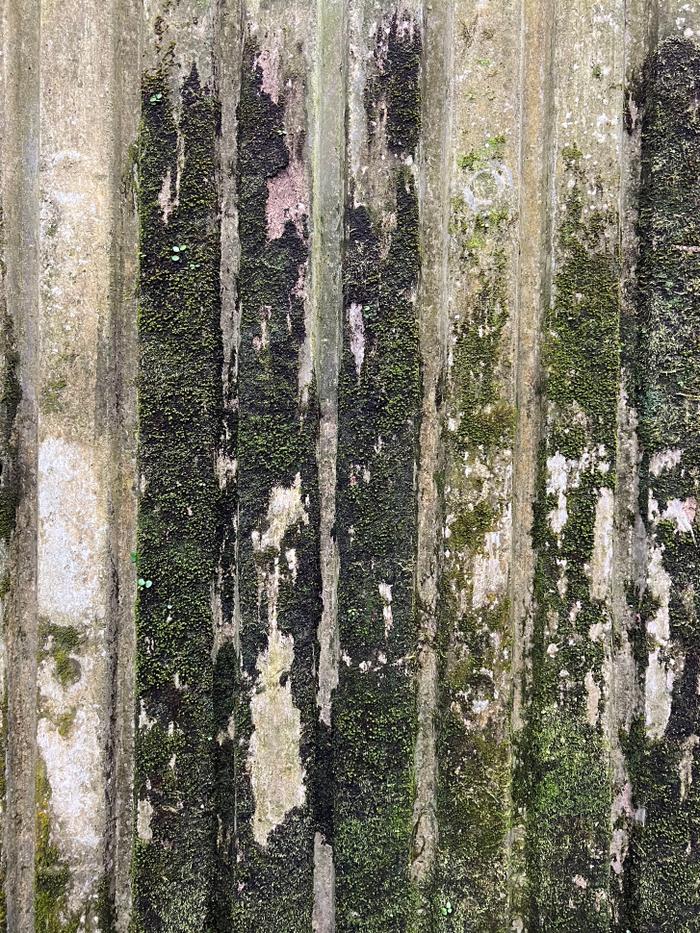

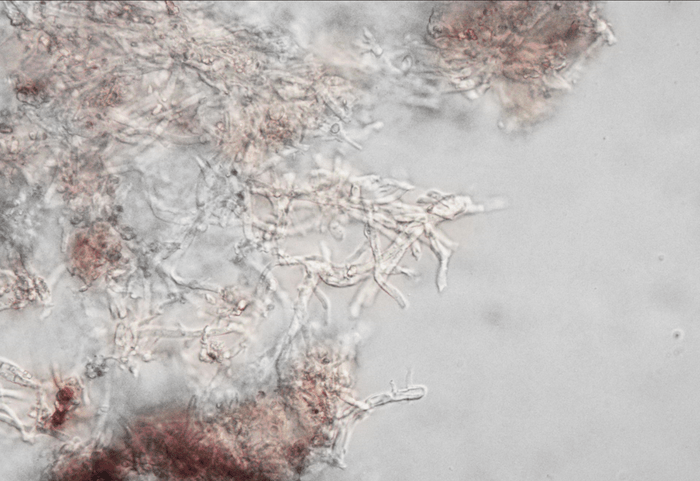

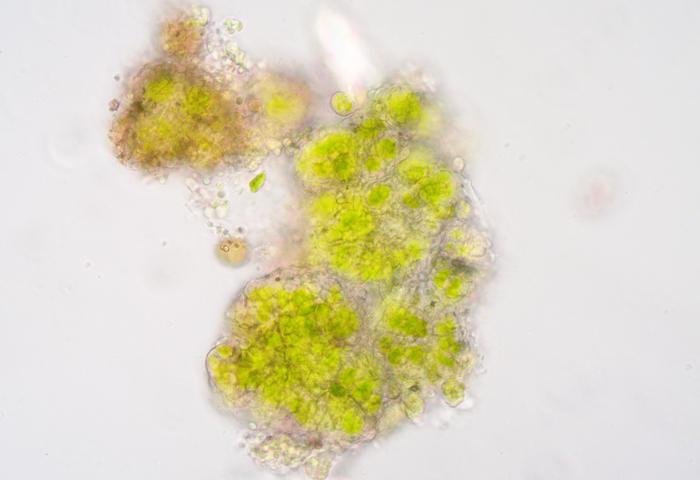

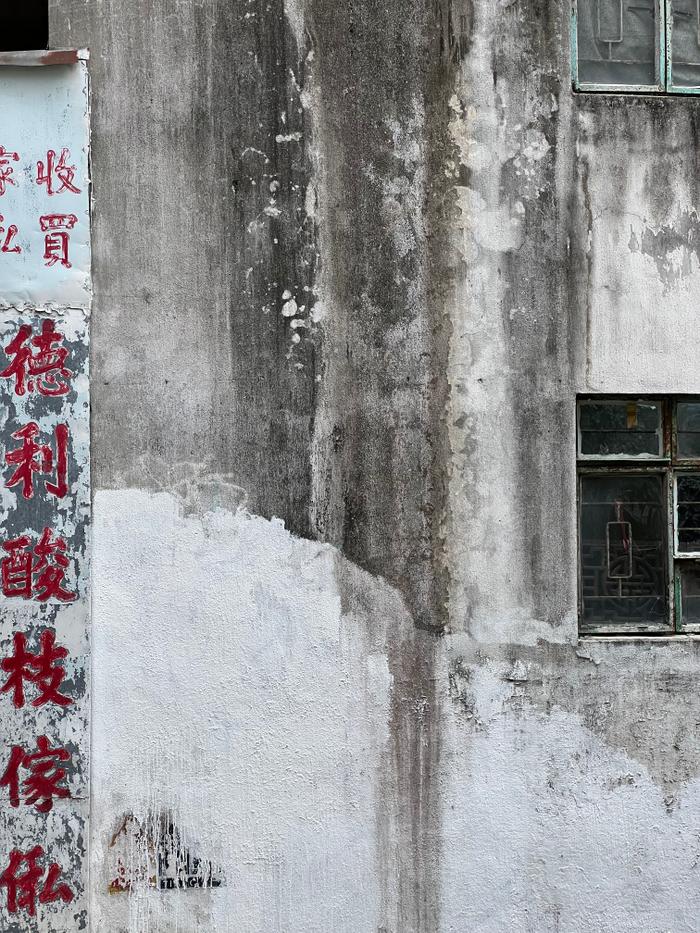

During your next walk in your neighbourhood, along the streets and familiar paths, take a closer look at the surfaces of the buildings you encounter. If you look really close, you’ll start noticing—maybe for the first time—the stains on coated concrete, the spots on painted walls, on shiny glass facades, on glazed bricks, smudges on lacquered wood, on stainless steel elements, and on plastic details. Where do such stains come from? Are they of human or nonhuman origin? What shape are these stains? How would you describe them? What is their colour? Where are they located? Come closer to the architectural skin and try to touch and smell it: What do they smell like? Are they soft or rather hard to touch?

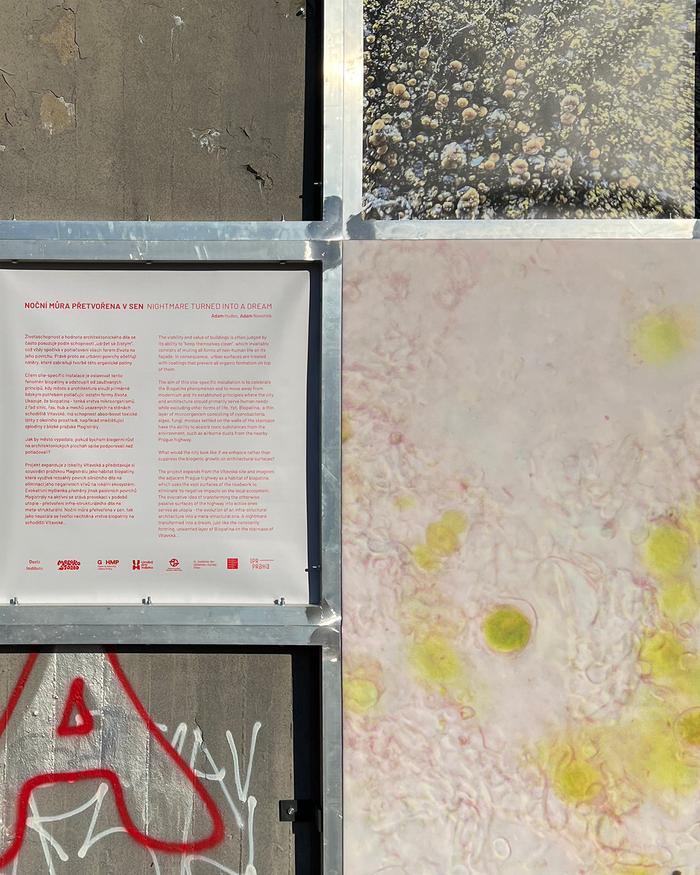

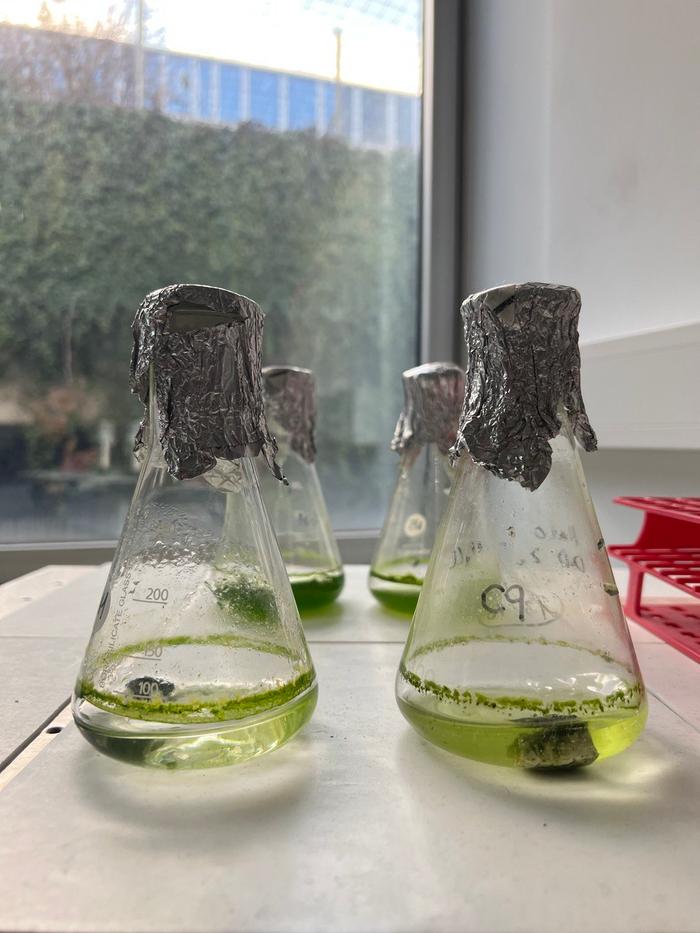

We rarely perceive stains or spots formed on uniform surfaces or notice any discoloration of static facades. If we look ‘deep’ enough, however, we will discover that stains are in fact a thin organic layer, called biopatina, naturally forming on all surfaces as the direct result of the interaction of the surface’s material with the environment. The interspecies cooperation of microorganisms forming biopatina does not require special treatment, artificial watering, fertiliser, or even our attention. This essay explores the layer of microorganisms on architectural organic skin—a phenomenon we call epidermitecture1 —with the aim of addressing ecological challenges that are the components of a single crisis, which is largely a crisis of perception.2