I

The global sales figures for noise-cancelling headphones amounted to at least $5 billion in 2022 and are estimated to double within a decade. “Silence is now big business,” it has been written in response.1 But the point of such devices is of course not simply to mute auditory distractions and curate meditative islands of quietude. The desire for noise control, instead, indexes much larger constellations: a critical urge to manage and fully design our auditory environments, extract listeners from a world of unwanted sounds, and recast that world on our own terms as a more hospitable world. Surely, available products rarely succeed in shutting out extraneous disturbances and discomforts altogether. What they bring to the fore, however, is a profound need for reliable infrastructures that secure conditions for the possibility of immersive experience, for protective enclosures that tone down unwanted interferences and allow us to yield to what resonates with our wants and wishes. As a technology that neutralizes incoming sound waves with counter-phase waves, noise-cancellation devices at heart promise us to leave a world we fear, resent, or find overwhelming, and exchange it for another world that’s more accepting and accommodating—a world of song and voice in whose echoes and reverberations we can safely bathe.

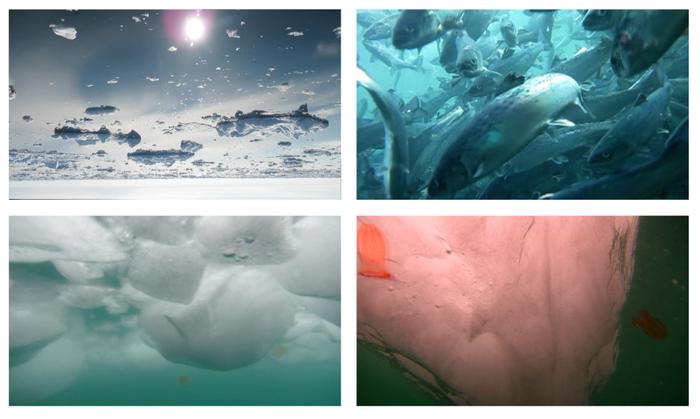

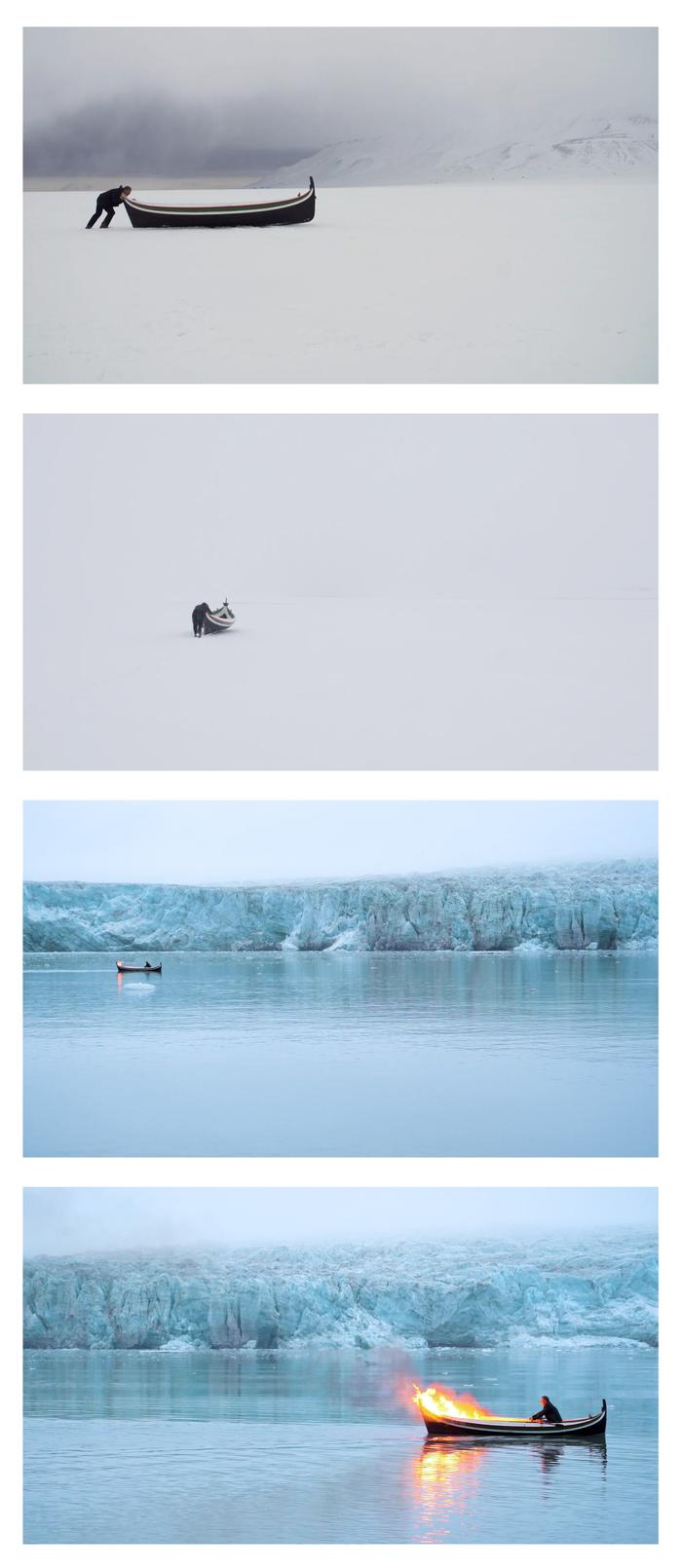

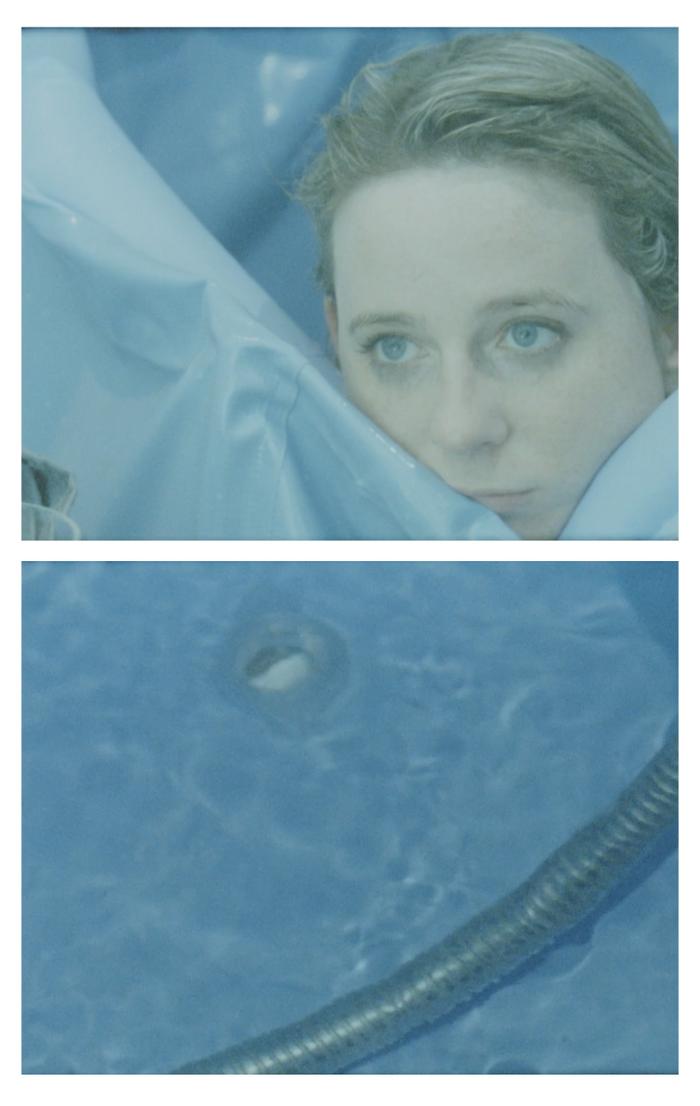

The Latin “immerger” entered English in the 17th century, a verb meant to describe acts of dipping one thing into another, of plunging what’s solid into something liquid. Priests immersed the young in rivers and ponds to launch their lives as true believers; they delivered bodies from themselves to name them anew and prepare them for higher callings. The modern usage of the verb “immerse” retains the old reference to transformative encounters with fluid substances: immersive images wash over our senses and transport us to imaginary elsewheres, immersive surround sounds in state-of-the art cinemas flood our audition and make a film’s projection appear more real than reality. To be immersed into something is to experience a certain dissolution of the body’s or mind’s limits, a process of entanglement between us and what is not us that suspends existing demands for autonomy, agency, and self-determination. Immersion halts the workings of ceaseless willfulness and self-consciousness; it invites us to go with the flow, to get carried away, because it defers the gravity and the constrains of the everyday, the need to mark borders and claim identities, the mandate to be someone and inhabit definite positions. Immersion transforms precisely because it relaxes the burdens of being, be they physical or psychology, and—temporarily—features becoming as the primary engine of what it means to be alive. In states of immersion, whether we bathe in oceans of images or waves of sound, everything assumes the status of a verb, becomes fluid, assumes the elemental qualities of water.

Over the last years, a steady current of academic writing has embraced water’s immersive qualities—a reorientation toward the oceanic—as laboratories to recalibrate dominant notions of ontology, epistemology, ethics, and aesthetics. In these accounts, water carries untapped potentials to decenter stubbornly anthropogenic views of the world and prepare humans for more symbiotic encounters with the non-human or the more-than-human world. In Wild Blue Media, Melody Jue reenvisions our position on planet Earth from the perspective of a scuba diver: of bodies floating under the ocean’s surface, emancipated from both the pressures of gravity and the rigidities of bi-pedal verticalism.2 Oceanic immersion, Jue proposes, teaches the art and ethics of buoyancy. It simultaneously reveals and challenges the terrestrial and gravitational biases that undergird most of the West’s ideas of progress and modernity as much as the repertoires of instinctive positions, embodied habits, and figures of thought. As both a material and an imaginative space of submersion, the ocean affords human subjects to interface with their environments less with their ears and eyes, and more with their lungs and the apparatuses that enable breathing in liquid surroundings. And in this, the experience of scuba diving has the capacity not only to expand what we take for granted about media, networks, and storage devices, but to estrange readers and writers from the terrestrial strictures of desks, libraries, and lecture halls. Oceanic immersion opens our minds to entirely new—but perhaps also very old—forms of knowing and engaging with the world.

In Waves of Knowing: A Seascape Epistemology, Hawai’ian scholar Karin Amimoto Ingersoll remains mostly above the ocean’s water as she explores indigenous ideas and practices of surfing, and yet she advocates a reorientation that—like Jue’s—no longer privileges land over water, the vertical over the horizontal, but instead understands ocean, wind, and human navigation as interconnected systems, as a meshwork of passageways that enfolds one element into the other.3 Surfing, for the Kānaka Maoli, is a way of being and staying with the ocean, and Ingersoll is adamant about claiming and reclaiming surfing as a local practice, a way of knowing the sea that has resisted two centuries of colonialism, militarism, and tourism. She has little patience with the relentless circuits of international surfing competitions and the privileged breathlessly chasing the thrill of big waves, even if they present their efforts as being in sync with the forces of nature. For her, surfing is as much a spiritual as a physical practice, an art of knowing the world that deeply resonates with native cosmologies. The ocean’s waters at once center and decenter. Oceanic people know how to attune their bodies to constant movement and fluctuation. Their world isn’t one of boundaries, walls, and properties, but of relationality, symbiosis, co-making, transspecies communication, and immersive co-dependency. As water’s movement and life transcends the binarisms between linear and circular time, culture and nature, it makes us think of human bodies and minds as no more and no less than mere crossroads within much larger dynamics.

Seascape thinking, as it dips into the absorptive energy of liquids, deheroizes notions of human agency and unbridled self-determination whose unchecked use have largely fueled extractivist approaches to the non-human and elemental world, past and present. In its praise of the anti-gravitational power of immersive experiences, it at once echoes and transcends what modern headphone subjects pursues inside their bubble of sweeping, largely undisturbed soundscapes. Noise cancellation promises oceanic sensations of sound within tightly sealed technological enclosures. It spares individuals painful exposures to the disturbing soundscapes of the present world by offering them different interactions within the safe, mediated, and more hospitable environment of their auditory devices. It cuts out noisy interferences in favor of a world in which we can welcome interference—the seemingly boundless dissolution of structuring borders between inside and outside, between the material and the immaterial, between mind and matter—as a way of staying with the world without suffering its intolerable burdens, of bathing in protected waters. While seascape epistemologists may entertain similar ideas about the need to dissolve the hardened boundaries of modern subjectivity and tap into transformative power of resonant experience, they certainly beg to differ from headphone ontologists when it comes to questions of enclosures, media, and mediation. The ocean, for Jue or Ingersoll, figures as a medium in its own right, an elemental medium; it neither needs mediated representation nor technological enclosure to afford its immersive powers; it in fact questions the very hierarchical logic of containment—between nature and culture, land and water, body and technology—that energizes noise cancellation’s own version of immersion. The ocean’s water is a verb, not because we want it to be so and engineer it as such, but because it precedes and transcends the power of wanting, of willfulness, of human intervention. In the world of Jue’s scuba diver and Ingersoll’s indigenous surfer, headphone divers are little more than another variant of extractivism—of what xwélmexw (Stó:lō/Skwah) scholar Dylan Robinson critiques as “hungry listening.” 4