Still from On being and Bathing (16mm film, 09.26, 2021) Anna Ulrikke Andersen and Abi Palmer

Still from On being and Bathing (16mm film, 09.26, 2021) Anna Ulrikke Andersen and Abi Palmer

Still from On being and Bathing (16mm film, 09.26, 2021) Anna Ulrikke Andersen and Abi Palmer

The bathroom was kept closed for 50 years. In 2004, Museum Frida Kahlo finally opened her bathroom. When she died in 1954, Diego Rivera, her husband, locked the room and ordered it to remain closed until at least 15 years after his death. The reasons for his wish are unknown; it is also unknown why Museo Frida Kahlo, situated at her house Casa Azul since 1954, took so long to free the bathroom and the objects inside it—Diego Rivera died in 1956, following his wishes the bathroom should have opened in 1971.

Fifty years have passed since Frida Kahlo’s death, and many stories have been told about her. A disabled Latin American woman who looms large as one of the most recognized artists of the 20th century, a pop icon reproduced to exhaustion in all kinds of products worldwide. When her bathroom was finally opened, it revealed an archive of personal objects: hundreds of clothes, fashion accessories, corsets, crutches, posters from Lenin and Stalin, medications, enamel recipients for enema, and previously unknown artworks, such as the 1934 drawing Las apariencias engañan (Appearances Can Be Deceiving).

One of the first people who had access to the room was the Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide, whom Museo Frida Kahlo invited to create a photo essay. In a video produced by the museum, Iturbide gives testimony about her experience entering the bathroom:

When I photographed, it was unconscious, but later I realized that they were objects of suffering: the Demerol, her crutches, and the political part that was kept there too [...] The object that impressed me the most was one of the corsets; it was very delicate and minimalist. Her corsets caught my attention because they are very aesthetic; even though they have to do with pain, they are not like those leather ones to be fastened. [...] I ended up admiring her a lot in the sense of how it was possible that with all those corsets, she could paint in her bed with the mirror on top or how she wore her hospital robe that says ABC to paint. It doesn’t matter if I love some paintings and others are not well finished because of her illness; how wonderful she could continue painting and not despair, or maybe she despaired, but her therapy was painting.1

There is an atmosphere of loneliness in Iturbide’s photographs, possibly informed by the discomfort and fear she experienced when facing Kahlo’s orthopedic objects. Her imagination conjures feelings of suffering, survival, and inspiration from a tragic existence trying to be healed through art. There is no room to imagine Kahlo wearing a hospital uniform and painting in a joyful or even ordinary way. It is uncanny to see an aesthetic and minimalist corset and the many prostheses she painted for herself. In 1925, Kahlo suffered an accident and had to stay in bed for almost three years to recover. She gave up studying medicine and started to paint more, producing several self-portraits while looking up at the mirror installed by her parents in the ceiling. As we can see in many photos, she also painted plaster corsets—now kept by Museo Frida Kahlo as part of the collection. In one photo from 1951 Kahlo is sitting in a chair with her top pulled up, showing the corset she painted with the communist symbol. She is looking at the camera and smiling.

Throughout her life, Kahlo certainly faced pain and exhaustion due to 39 surgeries, Poliomyelitis, the accident, abortions, and an amputation. But this doesn’t mean that her life should be reduced to tragedy and that her work should be read as art therapy, a common misconception about disabled and sick artists, whose work is rarely granted the status of simply being art. The bathroom was kept closed for 50 years. When it was finally opened, ableist ideas around Kahlo’s biography were repeated and reinforced, and not only in Iturbide’s testimony.

Looking at the photos from Kahlo’s archive, I would like to bring attention to one in particular [1], where we see part of the collection of corsets and crutches and a giant poster of Joseph Stalin raising his arm. They are all inside the bathtub. These orthopedic objects are like a small multitude around Stalin; the crutches almost stand up with him. It is not a usual reunion in a bathtub. I think about how the crutches, the corsets, and that political figure were the different bases of support that Frida Kahlo had. This weird, curious assembly can lead us to imagine acts of care as political and politics as a space of intimacy. We can be troubled by this strange assembly, not because of the orthopedic objects but by Kahlo’s admiration and support of a dictator.2 This bathtub could be a place to imagine a utopia where crutches, corsets, clothes, an admired idol, Demeron, and art pieces meet like a chosen family.

[1] Untitled, from the series El baño de Frida Kahlo (Frida Kahlo’s Bathroom), 2006. Courtesy of Graciela Iturbide.

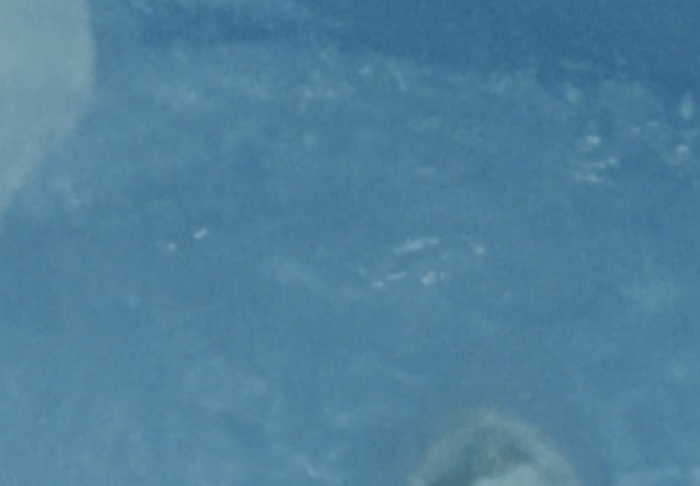

Maybe that same bathtub was the scenario of the self-portrait Lo que el agua me dio (What the Water Gave Me) [2] from 1939. She is lying in the water, and the spectator is positioned in the same perspective as her torso, looking at her feet, which appear outside the water, leaning at the end of the bathtub. With red painted toenails, her right toe (which is usually considered “deformed” due to Poliomyelitis) bleeds, and a drop runs towards a bird lying on the top of a tree. In the water, there are several figures, objects, and structures floating: a wilted flower with dried vines; a Tehuana dress with a yellow skirt and red bodice; two nude female figures on what appears to be a sponge; a heterosexual couple dressed traditionally; an island that has an erupting volcano out of which a tall building emerges. There are numerous elements, but here, I would like to point out the dualisms in the composition: tradition and modernity, Mexican and European, lesbian and heterosexual, what is in evidence, and the hidden parts under the water. Dualism could be easily understood as polarization or the impossibility of coexistence. But in this self-portrait, we can feel the opposite: a fertile system of living together, all the possibilities and negotiations of being multiple. Maybe it is not by chance that she thanks the water: it’s where things get mixed, the weight of gravity is lost, the muscles relax, and one can feel cured, even if it only lasts as long as bath time. Kahlo said: “Each (tick-tock) is a second of life that passes, flees, and does not repeat itself. And there is so much intensity in it, so much interest, that the problem is only knowing how to live it. Each one has to solve it as they can”.3

[2] Frida Kahlo, Lo que el agua me dio (What the Water Gave Me), 1938

She was the center of her art, always investigating the multiple possibilities of her body and constructing it at the margins of binarism. We can meet many Kahlos by the way she used to dress: in full costume, androgynous, in a skirt, European, Mexican, with a painted corset, with a prosthesis in the form of a red boot adorned with Chinese embroidery and a bell, wearing masks. A small self-portrait never seen before [3] was also found in that same bathroom, where she drew herself as she was and much more. We can see her hair and earrings, her corset, her leg afflicted by polio, and her genitalia almost in the center. But there is also what we do not see, which she knows very well: the spine as a Greek column, the left leg stamped with blue butterflies, and a transparent dress covering her whole body. There does not seem to be loneliness, but technology. There appears to be not helplessness but a complete knowledge of herself and the world. There is choice, control, freedom, and harmony. A dress that covers and reveals her. The viewer can look inside, and she looks back at the world. The title says: Las apariencias engañan.4

Researching this piece, I found an exhibition from 2012 with the same name: Las apariencias engañan: los vestidos de Frida Kahlo (Appearances Can Be Deceiving: Frida Kahlo’s Dresses). Organized by Frida Kahlo Museum and Vogue Mexico in association with BMW, the exhibition showed several of the 300 dresses found in the bathroom. Surprisingly, in an interview the curator Circe Henestrosa argues that Kahlo chose to wear traditional Tehuano clothing because she wanted to hide her disability and prosthetic leg.5

[3] Frida Kahlo, Las apariencias engañan (Apperances can be Deceiving), 1934

In the Winter and Spring of 2021 in Chicago, Marley Molkentin and Kennedy Healy decided to shoot a photo essay to make in-home care public. It was published with a conversation recorded in January 2022 on Disability Visibility’s website.6

My name is Kennedy. I’m a 27-year-old Fat, Queer, Crip. I receive state-funded home-care services that allow me to utilize Personal Assistants, or PAs, who help me with bathing, dressing, hygiene, household chores, and more. Though my life is structured around care, it is a reality that is invisible to many people around me.

I’m Marley, I’m 23, and I graduated college with a photojournalism degree and no job in the middle of the pandemic. I found Kennedy’s PA job posting in a queer Facebook group. I was the first PA she hired under Covid, essentially trusting me with her life due to her high-risk status. Though I knew nothing about care work, I spent the next year working for her, learning from her, and ultimately creating with her.

“Other hands, my decisions” is one of the mottos of the Independent Living Movement that has been fighting for decades for disabled people’s right to have Personal Assistants (PA) to support7 their needs instead of having to live in assisted living without the ability to make choices about everyday routines and activities. “Choice, control, freedom, equality” are the fundamental concepts of that movement. “I remember discussing Personal Assistance, and Sole said: ‘It is like, if you want to have two or three showers a day, you can,’” is the testimony activist and writer Elena Prous8 gave in the homage to Soledad Arnau9, one of the pioneers of Independent Living Movement in Spain, who passed in the middle of 2021.10

Marley and Kennedy decided to make visible the relationship between a PA and a body considered dependent by taking pictures of their rituals of care. Bodies like Kennedy’s are usually visually underrepresented or shown as tragic lives that aren’t worth living. Care during Covid: Photo Essay on Interdependence focuses on the importance of talking in the first person about vulnerability without perpetuating the thesis of personal tragedy.

Half of the pictures were taken in Kennedy’s bathroom—how could the bathroom not be there? The room is pink [4], like a box; there are no barriers, and looking at it, I have the sensation of almost being there, near Marley and Kennedy. It is dry and wet simultaneously; there are no stairs or bathtubs, only a chair. Kennedy is naked and seated; Marley is washing her and dressed. Kennedy looks at the camera. She was not kept in by the frame by chance; this is a posed portrait. There is no shame, no pity, there is choice, control, freedom.

In another picture [5], all we can see is Kennedy’s naked, wet back supported by the metal chair. Marley’s hand runs a small piece of violet soap on her. It is about structure: the spine Kahlo represented so many times in her self-portraits as the Greek column is not in the center of the image here, but pending to the right. The line begins between her butt muscles, the only part that is precisely in the middle of the picture; following this line up to the scar near her neck is not a straight journey. The bones are curved, and the fat rolls of her back are like waves; the only straight structure is the back of the chair. There is no Vitruvian ambition.

The standard Western bathroom is strict about body movements: lie in the bathtub, stand by the sink and in the shower, sit on the toilet or bidé. All the furniture is rigid and fixed on the floor. One of the most important guides of Western construction is Architects’ Data by the German architect Ernst Neufert. There, all the spaces are translated into measures following some principles, like “Man as measure and purpose,” “The universal standard,” “Body measurements and space requirements,” and “Geometrical relationships.”11

Thiago Hersan, for Queer Graphic Laboratory, 2017

“In 1932, British artist Paul Nash designed a bathroom for the Austrian dancer and film star Tilly Losch. The bathroom was commissioned by poet and surrealist art collector Edward James for his London home at 35 Wimpole Street, where he lived with feted Losch during their short and tempestuous marriage”. This is how the curator Catherine Ince starts the article “A Bathroom for a Dancer,” about this iconic glass bathroom. It is about luxury, being unique, pieces made specially for Tilly Losch.12 The article’s name made me think about a bathroom for a dancer, a wheel dancer who moves around the room and does everything seated—the luxury of having a bathroom that considers your unique, extraordinary body and its choreography.13

The World Health Organization estimates that there are 1.6 billion disabled people worldwide —1 in 6 people—.14 However, the standard bathroom does not include these bodies. Adaptation and imagination are the dance this community will do to survive in ordinary facilities, as we can see in a Whatsapp group created by and for people affected by Muscular Spinal Atrophy (SMA):

A: Does anyone have folding shower chairs for traveling, and what brand is it?

B: I use a reclining beach chair.

C: Ours is not folding, but it is removable. There are folding ones, but we prefer the other one.

D: The folding ones we saw did not have folding arms, which, in our case, is essential. I’m not saying there are none because we didn’t insist too much. I am talking about a shower chair and WC with wheels.

A: as long as it fits in the suitcase.... thanks

Different links and photos for shower chairs appear, with comments about how to use them. The chairs have the typical color and design of medical objects. You cannot find them in Ikea, Leroy Merlin, or other furniture shop; they are available at orthopedic stores, Amazon, and Lidl. You cannot find them in the books published by Taschen about iconic chairs. There isn’t a famous name for a bathroom chair or a wheelchair like Barcelona, Eero Saarinen, Eames, etc.

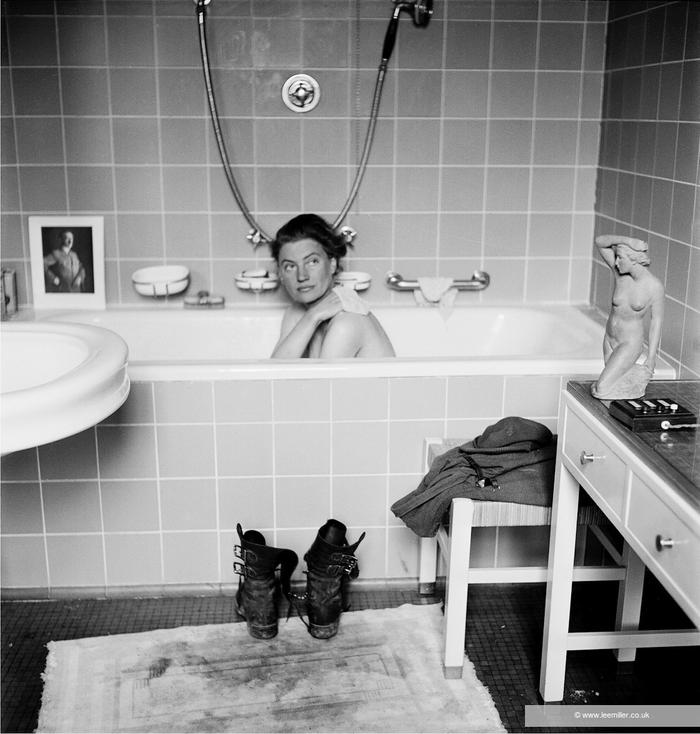

[6] Lee Miller in Hitler’s bathtub, Hitler’s apartment Munich Germany, 1945. ©LeeMillerArchives

On April 30, 1945, the photographer Lee Miller (1907-1977) [6] posed naked in Hitler’s bathtub, the same day he and Eva Braun committed suicide. A surrealist artist, photographer, journalist, and model, Lee Miller’s legacy used to be reduced as Man Ray’s eye muse in the art piece Object of Destruction. During World War II, she was an accredited war correspondent attached to US Army. In the Vogue edition of June 1945, a magazine Miller had previously collaborated with as a model and fashion photographer, she published images of the war, including a shot of a pile of skeletal bodies. “Believe It” was the headline chosen for the article. She was among the first people to enter the Buchenwald concentration camp after liberation.15

Coming back from the concentration camp of Dachau, Miller and the photographer David E. Scherman from Life Magazine traveled to Munich. They entered into Adolf Hitler’s apartment since the place had been requisitioned by the US Army and used as a billet. Without knowing that the residents would commit suicide a few hours later, she removed her boots and clothes, covered with mud from the concentration camp, and soaked naked in the tub. She placed a portrait of Adolf Hitler behind her, set up the camera, and asked Scherman to “press the botton”.

The photograph became famous and was reproduced in many articles throughout the following decades. My attention usually goes first to the small sculpture on the right. It is a woman naked on her knees with the right arm raised above her hair. Die Ausschauende (The One Who Looks Out), from the artist is Rudolf Kaesbach. Lee Miller looks at us, and the statue looks at her. It is a piece inspired by Venus de Milo, the muse without arms, the classical ideal of beauty, and a disabled icon. Hitler loved classical art and would have murdered Venus de Milo through the euthanasia Nazi program that killed two hundred thousand disabled people during the war.

Miller also raised her arm, holding a washcloth, cleaning herself, or performing a bath. For the first time in months, she was the photo’s subject. Miller undressed the uniform and the camera, the protections she had to face the unimaginable registered in images. She covered Hitler’s clean bathroom with the mud from the concentration camp. Maybe a little token of revenge.

They spent the night in the apartment. When they left, Miller took a towel embroidered with the initials AH, a perfume bottle, the framed photograph of Hitler. It must have taken courage to sit naked inside the most intimate place of your enemy, steal his objects, and make them yours. She kept the objects. In 2012, they were displayed in Kassel at the Fridericianum for the 13th edition of Documenta. The bathroom photograph and Man Ray’s Object of Destruction were also there. They became fascist historic witness objects. Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the exhibition curator, says: “On a symbolic and also on a bodily level, Miller takes his place [Hitler], creates a substitution; in part she becomes the victimizer, washing herself of his crimes. It is a ‘mythic’ photograph—as if she were attempting to cleanse humanity of its sins.”16

After the war, Miller moved to London and, in 1949, to East Sussex at Farley Farm. She got married, and had a son. She had what we today recognize as post-traumatic stress disorder, and like many war veterans who lacked professional psychological rehabilitation, she self-medicated and struggled with depression and alcoholism. The war left a mass of mentally and physically disabled people. Lee Miller died at the age of 70, and after her death, Antony Penrose, her son, discovered photographs, negatives, and Vogue issues in the attic. In an interview for The Guardian in 2016, Penrose says that he had no idea about his mother’s accomplishments until he discovered the archive in the attic.

When she was alive, Miller successfully convinced everyone that she hadn’t done anything worth talking about. Tony says that when anyone asked her about her time as a war correspondent for Vogue magazine, she would say: “Oh, I didn’t do much, it wasn’t of any importance, and it’s all been destroyed since.”17

The Cuban philosopher José Esteban Muñoz says, “The here and now is a prison house. We must strive, in the face of the here and now’s totalizing rendering of reality, to think and feel a then and there. Some will say that all we have are the pleasures of this moment, but we must never settle for that minimal transport; we must dream and enact new and better pleasures, other ways of being in the world, and ultimately new worlds. (…) Both the ornamental and the quotidian can contain a map of the utopia that is queerness”.18

The bathroom can be a map of utopia. But not like Stalin, in Kahlo’s bathroom, or Hitler, in Lee Miller’s picture, desired. Through these three stories, we access archives enclosed and produced in bathrooms. How do we access these archives? How to look at them? They point out stories of failure: the ableist way Kahlo’s body and its performances are still read; the way spaces are constructed considering an idealized body, neglecting rituals of care through ordinary architecture; the impossibility of many to recover from the experience of fascism. These stories are about the body and its limitations, embodying the impossibility of the present and, through minimal actions, imagining a future. Entering the space, taking off the weight of gravity, relaxing the muscles, and feeling cured, even if it only lasts as long as bath time.

Endnotes

1 Museo Frida Kahlo. “El baño de Frida Kahlo”: Entrevista con la fotógrafa Graciela Iturbide. Author translation. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cyeo7yGFUNo&ab_channel=FridaKahlo

2 In the mid-1930s, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera considered themselves Trotskyists, and Rivera was the person who convinced Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas to offer Trotsky and his wife Sedove political asylum in Mexico. In 1937, they moved to Casa Azul. Kahlo and Trotsky became lovers, and she painted the self-portrait Autorretrato dedicado a León Trotsky in 1937. In 1939, Kahlo and Rivera became Stalinists, and Kahlo and Trotsky began to drift apart regarding political ideas. In 1940, an undercover agent working for Stalin killed Trotsky with an ice pick. From “Trotsky, el breve amor de Frida Kahlo por el que acabó en la cárcel”. El Independiente, 23/08/2019, available at https://www.elindependiente.com/tendencias/2019/08/23/frida-leon-desconocido-affair/.

3 Graciela Iturbide. El baño de Frida Kahlo. DF: Galería López Quiroga, 2008. Available at https://issuu.com/17edu/docs/el_ban_o_de_frida.

4 The thoughts about the piece Las apariencias engañan were developed in contribution with Dr. Yuji Kawasima for the lecture “Entre el 1 y el 3: citas entre el VIH y la diversidad funcional en el arte contemporáneo” held at Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía at December 2, 2022.

5 Available at https://artsandculture.google.com/story/rAUBPDLcNAzkJA?hl=es.

6 Available at https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/2022/02/08/care-during-covid-photo-essay-on-interdependence/

7 “‘Personal assistance’ then means that we compensate our disabilities by delegating tasks to other persons. These tasks involve activities which we cannot carry out ourselves or which we are not good at. We delegate in order to have the time and energy to specialize in those activities which we can perform well. ‘Personal’ connotes that the assistance has to be customized to my individual needs. ‘Personal’ also means that the user decides what activities are to be delegated, to whom and when and how the tasks are to be carried out.” In https://www.independentliving.org/docs2/enilpakeytoil.html.

8 More information about Elena Prous at https://laincontenida.wordpress.com/.

9 Soledad Arnau Ripollés (Nules, Castellón; April 2, 1971 - October 28, 2021) was a feminist activist, philosopher and sexologist. She founded the Foro de Vida Independiente, Divertad, and Diversex, a space to defend the sexual rights of disabled people—more info about her at https://soledadarnau.com/soledad-arnau/.

10 The Spanish activist Antonio Centeno writes about the illusion of independence and the concept of interdependency: “I have an official certificate stating that I am ‘grade III dependent.’ To reach that conclusion, a multidisciplinary team asked me, ‘ can you drink water on your own?’. I answered no, because to drink my Personal Assistant places the glass to my lips and tilts it. But, strictly speaking, can anyone answer affirmatively? Behind that glass of water, there are thousands of people holding it; whether you drink with your own hands or with those of your Personal Assistant, the difference between 10,000 hands and 10,001 should not be significant [...]. We all depend on each other, contribute to each other, no one lives ‘by herself,’ interdependence is the only real thing, it is impossible to be without the others.” My translation. In Antonio Centeno, “La asistencia sexual, recuperar nuestros cuerpos para recuperar nuestras vidas.” elDiario.es, Madrid, 17/2/2020. Author translation.

11 Ernst and Paul Neufert. Architects’ Data. Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

12 Catherine Ince, “A Bathroom for a dancer.” In Javier Fernández Contreras, Roberto Zancan (ed.), Intimacy Exposed: Toilet, Bathroom, Restroom. Leipzig, Spector Books, p. 22.

13 Quoting Rosemary Garland Thomson in Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. Columbia University Press, 1997.

14 More info at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health#:~:text=Key%20facts,1%20in%206%20of%20us

15 Vincent Aletti (org). Issues: A History of Photography in Fashion Magazines. Phaidon Press, 2019, p. 6, 7.

16 Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. On the Destruction of Art—or Conflict and Art, or Trauma and the Art of Healing, Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2012, p. 20.

17 Available at https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/mar/19/lee-miller-the-mother-i-never-knew.

18 José Esteban Muñoz. Cruising Utopia. New York University Press, 2009, p. 24.

“Bathrooms can be more than of (im)pure function. As spaces of particular embodiment, they hold potentialities for utopian scenarios or remain repositories of their previously imagined versions. Júlia’s essay imagines acts of care as political, and politics as a space of intimacy. Here, caring is seen as making an effort, acting on, staying-with and therefore becoming a tool of empowerment of the self and others. Is there potential for actively reimagining bathrooms as utopian sanctuaries, offering care and a refuge for everyone, irrespective of their outward performance, to wash away the burdens of the productive world?”

- Jakub Węgrzynowicz

“Julia’s work raises for me a shared interest in the partial archive, the lost archive, and alternative forms of thinking with an archive that allows one to work around what is otherwise unknowable and incomprehensible. There seems to be two different kinds of utopias at play that I am not entirely sure how they are reconciled. On a separate note: I am still puzzled by the discrepancy between the two fascisms that are introduced in the writing (under Stalin and under Hitler) and the two different attitudes from Kahlo and Miller regarding these histories. How does the author reckon with this discrepancy?”

- Pauline Shongov

Júlia Ayerbe, “The bathroom may be a space for utopia,” Metode (2024), vol. 2 ‘Being, Bathing and Beyond’