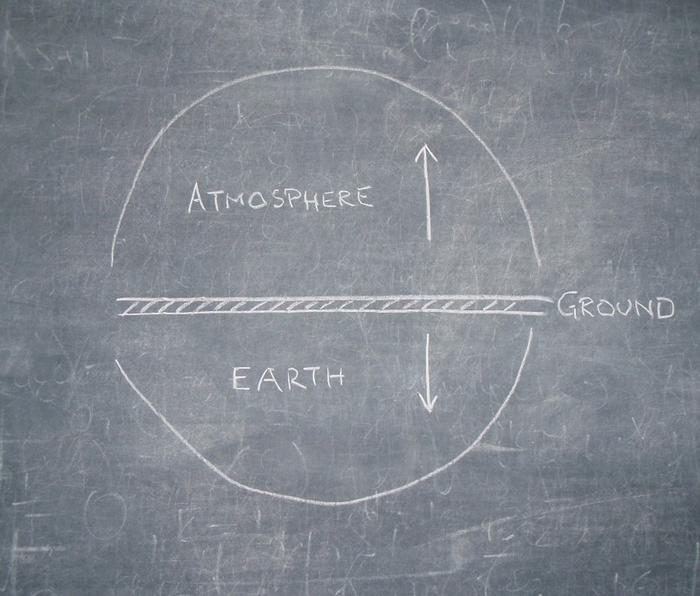

Let’s compare these passages. For both Shepherd and Gibson, atmospheric air is up above, and the earth is deep down below. But what lies between sky and earth? For Gibson, it is the ground, conceived as a solid platform of support that separates the air above from the earth below. But for Shepherd, what lies between is – well – everything, the ‘total mountain’. What’s going on here? How can there be such different views? And which is right?

In Gibson’s characterisation, as we’ve seen, the ground is an ‘earth-air interface’. Now by definition, an interface has two sides: whether a top side and an underside, or an outside and an inside. While the interface serves to keep the two sides separate, confined to their respective domains, it is also perforated by holes or keys that allow information, and sometimes materials, to pass from one side to the other. A metalled road or pavement, for example, may be perforated by drains that allow rainwater through to underground channels, or manholes that allow human access to subsurface infrastructure. The paved surfaces of the city, of course, also provide support for its inhabitants. Indeed, the campaign to pave the urban environment, in the modern era, was driven above all by its twin functions of support and separation. On the one hand, the paved surface provided a secure foundation for fast and efficient transport, above all by means of wheeled vehicles, which might otherwise become stuck in mud, or be overturned by surface irregularities. On the other hand, paving was considered of benefit to public health, since it sealed the ground, preventing the stench of the earth from rising into the air, where it was believed to cause illness among those who breathed it.

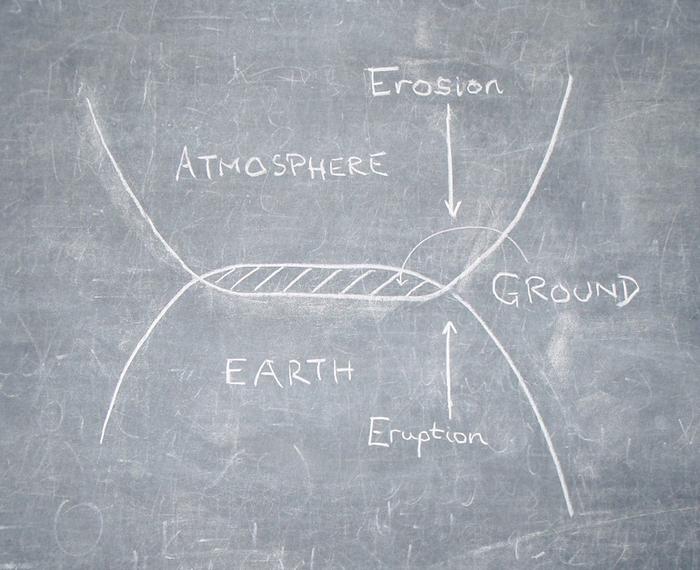

Yet on a paved surface, nothing can grow. For growth to occur, it is necessary for carbon dioxide in the air to bind with rainfall already absorbed into the soil and taken up by the roots, in the presence of sunlight. This is photosynthesis, and all life depends on it. Thus, in the growth of living things, earth and air meet and mingle. Where the ground has been paved, growth is only possible through cracks in the pavement – that is, until the surface itself, overwhelmed by the elemental forces of earth and air, eventually crumbles.

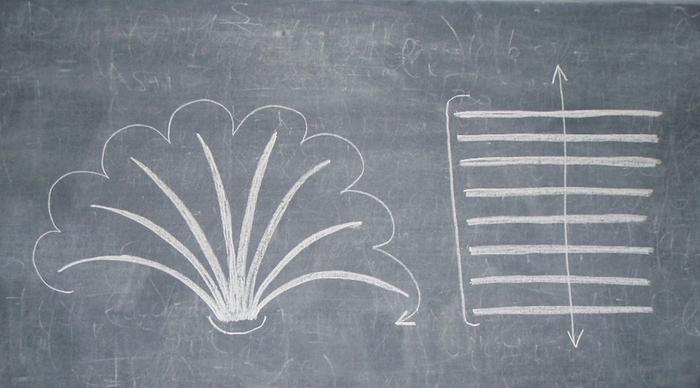

Let’s now leave the city for the countryside, or join with Shepherd in the mountains. Here, the ground is not paved. And its surface has only one side, not two. It is not an interface, it is not hard, and for plants at least, it is not a surface of support but a medium. Plants grow in the ground; they don’t rest upon it. What matters to the plant is the depth to which light can penetrate. From the plant’s point of view, indeed, the ground is not really a coherent foundation at all, but an indistinct and permeable limit of illumination, above which it shoots out green leaves, but below which it adopts the different habit of root growth. How can we describe this kind of surface?

To answer this question, I would like to draw an analogy between the ground of habitation and the page of writing. It is an ancient analogy, that can even be traced etymologically to the origin of the English word ‘page’, which comes from the Latin word pagus, meaning an area of inhabited countryside with its farms and fields (from which are also derived English word ‘peasant’, for the farmer, and the French word ‘paysage’ for the landscape he tends). The act of writing, with pen on parchment, would then be likened to that of tilling the fields with the plough. In the days when almost everyone knew how to handle a plough but few could write, it was a natural comparison to make. Now, of course, the situation is reversed. Almost everyone can write, but how many still know how to handle a plough?

Now the parchment that medieval scribes used for their principal writing material was highly absorbent. It was also very expensive. For that reason, it was common for the same material to be used over and over again. To reuse a parchment that has already been written upon, you have first to scrape the surface with a knife, so as to remove as much of the original traces as possible. You can then write again. In principle, you can repeat this operation until eventually, the parchment is scraped so thin that it is no longer usable. However, since the material is so absorbent, the traces of previous writing can never be completely removed. Thus, on a parchment that has been used several times, recent inscriptions appear to cut through the ever-fainter traces of earlier ones, giving rise to what students of writing call a palimpsest.

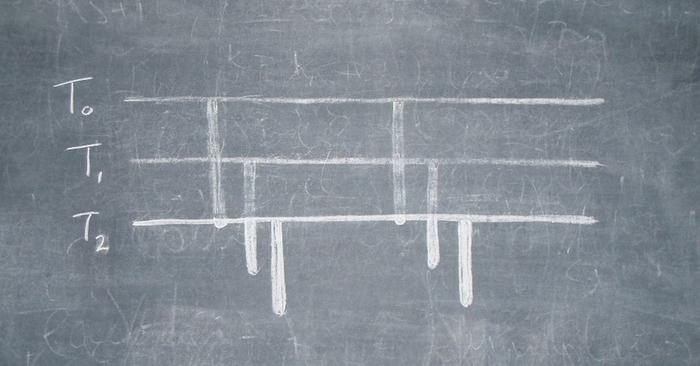

Modern readers, conditioned by their familiarity with the printed word, can all too easily jump to the conclusion that the formation of the palimpsest is equivalent to overprinting, in which one layer of inscription is simply added over another. But a closer look at how the palimpsest is formed reveals it to be precisely the opposite. Let me explain by means of a diagram (Image 2). This shows a parchment in exaggerated cross section, such that a line of ink appears as a vertical mark, as wide as the line is thick and as deep as the ink sinks into the fabric of the parchment. In the diagram I have indicated two lines inscribed at time T0. Later, at time T1, the surface is scraped, and two new lines are inscribed close to the old ones. The same is done again at time T2. Now, looking at the surface at T2, observe what has happened to the traces. The original traces from T0 are only just visible right at the surface, and will surely disappear if the parchment is used again. The traces from T1 are shallower than they were, but still clear. Deepest of all are the most recent traces, from T2. Thus, far from past inscriptions sinking ever further down as new ones are added on top, quite the reverse occurs: it is the past that rises, even as it is undercut by the present.