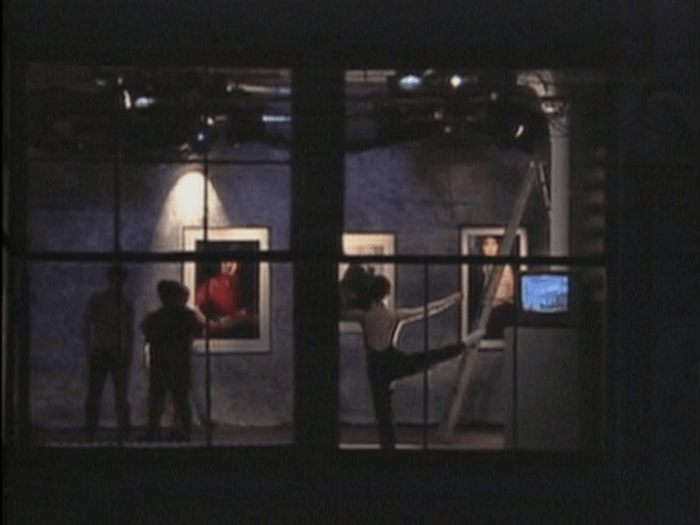

Still from Two Moon July, directed by Tom Bowes, 1986. Produced for The Kitchen by Carlota Schoolman. Courtesy of The Kitchen.

Still from Two Moon July, directed by Tom Bowes, 1986. Produced for The Kitchen by Carlota Schoolman. Courtesy of The Kitchen.

Still from Two Moon July, directed by Tom Bowes, 1986. Produced for The Kitchen by Carlota Schoolman. Courtesy of The Kitchen.

Still from Two Moon July, directed by Tom Bowes, 1986. Produced for The Kitchen by Carlota Schoolman. Courtesy of The Kitchen.

The year is 1987. You turn on the television and flip through a few channels before landing on that of the U.S. public broadcaster PBS, where the opening scene of a program catches your eye: a close-up shot of several building tops adorned with water towers, silhouetted against a hazy sky at twilight. A nearly full moon sits in the frame’s upper right quadrant. Its double—a second, smaller orb—hangs in the sky below and to the left of it. The title appears over the opening shot: Two Moon July. The staggered, diagonal positioning of the words places “moon” just below the smaller orb, with the pair of “o’s” cradling its image. The soundtrack enhances the scene’s sense of mystery via ambient synthesizer notes that layer together to create dissonance.1

The title disappears, and the cityscape remains briefly before fading to black. With the music continuing, another image of the city at twilight emerges on the screen’s right half, this time depicting a denser section of high rises and skyscrapers under a cloudy sky. The opening credits begin to roll on the left side, listing different artistic disciplines—performance, visual art, video, and film—and a corresponding set of artists’ names under each header. With the anticipation of these initial moments mounting, one might start to wonder: What realm is this television program conjuring? What is art’s role within it?

Following the introduction, a tightly framed shot heightens these questions: a television screen resting vertically on its side on top of a pedestal shows the same cityscape that has just been seen alongside the credits. Another act of doubling, the scene nests the depicted screen within the screen on which viewers watch the program. However, the environment surrounding the screens reveals differences. Whereas the television transmitting the program broadcast would most likely be situated in a domestic setting, the monitor captured in the footage appears in a space characterized by dramatic lighting and a series of four large-scale, black-and-white prints of human figures hanging on the wall behind—features commonly associated with an art gallery. The camera zooms out to reveal the television as part of an installation, with two additional matching screens on pedestals of different heights set at intervals in the space. As the lens continues to pan, three framed photographs of a female subject come into view on the wall to the right of the prints. Pulling back further still, the camera moves from within the space to an exterior vantage, framing through a row of windows the image of the artworks installed within a large loft. By this point, just over two minutes into the program, the relationship between the display of objects and the ways the camera captures the installation begins to hint at a fluid exchange between the presentation of art on television and the framing of television as art.

The establishing shot looking into the loft from the outside dissolves and reemerges to show the space from the same angle, this time animated with people: a dancer stretching, a technician repositioning a ladder. Cutting to a different section of the interior, the camera finds a group of musicians and another dancer engaged in similar kinds of warm ups. A caption appears on the screen’s lower left side, locating what has become an increasingly live scene in real time and space: “The Kitchen, N.Y.C., July 1985.” From there, the preparatory exercises and conversations among artists and crew culminate when a technician behind a soundboard speaks into a microphone, instructing the room: “Okay, get settled in. Clear the space for the performance tonight. Performers only, please...”2

Still from Two Moon July, directed by Tom Bowes, 1986. Produced for The Kitchen by Carlota Schoolman. Courtesy of The Kitchen. Shown here: Evan Lurie, John Lurie, Toni Noguiera, and Bill T. Jones.

Two Moon July (1986) is an hour-long “arts and entertainment special” directed by Tom Bowes and produced by Carlota Schoolman that premiered on PBS on Friday, September 11, 1987, with initial circulation across roughly 28 local affiliate channels.3 The institution responsible for producing the work is the same as the one hosting the performance in the program: The Kitchen. Founded in 1971 and initially operated as an artist collective by video artists Steina and Woody Vasulka, Shridhar Bapat, Dimitri Devyatkin, and musician Rhys Chatham, The Kitchen began with the aim of supporting the production and presentation of nascent forms of video art that had yet to be embraced by traditional institutions such as museums and galleries. Initially based in the former kitchen of the Mercer Art Center—a complex of theaters in downtown New York—The Kitchen functioned as an “electronic media theater.”4 In the institution’s early years, the collective oversaw a robust series of live events that quickly expanded beyond video to include programming in experimental music, performance, and dance. As The Kitchen’s scope of activities evolved, its institutional structure shifted: in 1973, the institution incorporated as a non-profit under the leadership of its first Executive Director, Robert Stearns, and moved into a loft space on the corner of Broome and Wooster Streets in Soho. While programming in its second home, which it occupied from 1973 to 1985, the institution began to present visual art, literature, performance, and film as a complement to the aforementioned disciplines.5 During this time, The Kitchen solidified its reputation and its institutional stature, becoming known as a “bastion of the avant-garde establishment, offering what is purported to be the latest and most daring artistic experiences.”6

Two Moon July portrays The Kitchen’s signature range of interdisciplinary, avant-garde activities in its Soho loft through a style that merges aspects of a variety show and a documentary.7 Following the opening sequence, the art installation featuring works by Jonathan Borofsky, Brian Eno, Robert Longo, and Cindy Sherman becomes the scenic backdrop for what the press release calls a “technical rehearsal,” during which ten artists—Laurie Anderson; David Byrne; Molissa Fenley, performing to music by Anthony Davis; Philip Glass; Bill T. Jones; Arto Lindsay and Toni Noguiera; and Evan Lurie and John Lurie—appear in different areas of the space to perform short, three- to four-minute segments of music, performance, and dance. 8 Notably, the camera serves as the only audience member, capturing the performances from varied angles and often placing the live art in relation to the visual artworks on display. In between the recorded action of the segments, the program cuts to excerpts of extant film and video works by Vito Acconci, Laurie Anderson, Michel Auder, Dara Birnbaum, Bruce Conner, Kit Fitzgerald and John Sanborn, George Lewis and Gregory Miller, Robert Longo, Eric Mitchell, and Bill Viola.9 Throughout, a series of short, narrative interludes—like the one in which the technician announces the start of the show—break up the performance and moving image pieces and provide a “frame” for the overall program. 10 These sections feature brief snippets of dialogue among the curators and technicians who are managing the production, revealing the behind-the-scenes labor of staging such a performance—from calling cues and running light and sound to wrangling talent. 11 In documenting a dramatized day-in-the-life of The Kitchen, Two Moon July not only invites the at-home television viewer to take a front row seat for an evening of varied performances, but also offers them a window into the mechanics of a live art space.

The special’s renderings of both the artistic and the behind-the-scenes activities are rooted in the realities of The Kitchen’s programming and operations. Just as each of the artists showcased throughout the program had previously exhibited or performed at The Kitchen, the individuals playing the role of curators and technicians had all worked for the institution in a staff capacity.12 Moreover, the director himself had deep ties to The Kitchen: Bowes was an employee of the institution for approximately five years, from 1978 to 1983, progressing through the roles of Technical Assistant, Media Technical Associate, TV Programming, and Video Curator before departing to focus on his own independent projects.13 Across these positions, his responsibilities included acting as in-house videographer for performances, curating video screenings to be shown in the institution’s onsite Video Viewing Room, and contributing to television productions.14

By taking on the format of a television special, Two Moon July introduces niche cultural content—the artistic happenings associated with a New York art center—into the context of a mass media platform. In bringing avant-garde practices outside art institutions and into the living rooms of new audiences, the program raises a set of questions about art’s accessibility and legibility: not only would the artworks and performances showcased stand in stark contrast to much of the era’s standard network television fare, but the central site of The Kitchen likely would have been unfamiliar to a large swath of the viewers tuning in across the country with varying levels of knowledge about or associations with the landscape of art institutions.15 Marketing and publicity materials indicate that the institution underscored this very novelty as a selling point. For instance, one promotional video calls the program “a stimulating adventure into the world of avant-garde performing arts.”16 To entice audiences to engage with the unknown, that same advertisement relies upon the wide acclaim of the featured artists and the institution as an entry point, opening with the invitation: “Welcome to The Kitchen, internationally recognized for its contributions to music, dance, and video. Spend an evening in New York City with some of the world’s greatest artists and performers….”17 The video goes on to illustrate its point by spotlighting selections from the special’s performances by artists who had presented seminal early works at The Kitchen before going on to develop a strong reputation within both art and pop culture, including Anderson, Byrne, and Glass. In its messaging and form, the advertisement foregrounds an impression of Two Moon July as a variety show that presents an exciting range of interdisciplinary art on television.

Marketing efforts like this one suggest that The Kitchen’s investment in broadcast was motivated in part by an interest in drawing new audiences into contact with The Kitchen’s favored forms of artistic practice. However, such promotions offer just one perspective on Two Moon July and the institution’s motivations in producing it—one that I suggest downplays how the work’s overarching framework experiments with the potential of television as a form of art.18 To shed light on this other aspect, the present article situates Two Moon July within a thread of The Kitchen’s programming that engaged with television as medium and mode of distribution in the years between the institution’s founding and the making of the special in the summer of 1985. I propose that, when interpreted in relation to this strand of institutional history, Bowes’s use of a televisual format to convey a portrait of The Kitchen’s activities and inner workings can be understood as an artistic choice to align the work’s form and subject, thereby infusing Two Moon July with self-reflexive commentary on how the institution strategically engaged with television programming as an evolving means of advancing aims that were central to its institutional ethos.

Still from Two Moon July, directed by Tom Bowes, 1986. Produced for The Kitchen by Carlota Schoolman. Courtesy of The Kitchen. Shown here: Michael Zwack, Anne DeMarinis, and Bob Wisdom; Cindy Sherman, Untitled.

Throughout Two Moon July, the dialogic interludes among the show’s technicians give presence to the kinds of responsibilities that director Tom Bowes undertook alongside his colleagues during his tenure on staff at The Kitchen. Drawing from his embedded role within the institution, Bowes transformed the work of performance and video curation, production, and documentation into material in the making of an original artistic product. With this study of Two Moon July, I begin from a similarly intertwined relationship with my subject, given my role as a curator at the same institution. Like Bowes, I also have found inspiration in institutional practices and activities as material for new production. Since joining The Kitchen in 2019, one of my areas of curatorial focus has been conceiving programming that engages with the institution’s history as a springboard to prompt reimagined methods for supporting and presenting experimental artistic practices today.

Over the past years, I became interested in an under-researched subset of The Kitchen’s activities that points toward rich lines of inquiry about how artworks travel across different networks and the role that institutions play in setting them into motion—questions that are of increasing relevance in today’s globalized and digitized world. The Kitchen developed and realized this tailored suite of program frameworks primarily between the 1970s and 1990s in order to extend its efforts beyond its New York space by distributing and circulating art throughout the United States and abroad.19 These initiatives included television productions such as Two Moon July, along with a video distribution program, national and international touring programs, and artist-designed posters and publications. To trace the trajectories of these various programmatic endeavors, I turned to The Kitchen Archives in New York—a set of materials to which my position on staff affords me full access, even though the collection is not yet fully processed.20 Referring to materials that represent a range of voices and perspectives—including video works and recordings of original performances, promotional materials, press clippings, institutional correspondence and grant applications, and oral histories of artists and staff members—I have sought to form a fuller picture of The Kitchen’s intentions for creating program models that facilitated the dissemination of artworks and to reflect on the impacts such programs had in bringing the institution and its favored avant-garde practices into contact with wider audiences across varying contexts.

While I was in the process of researching this subject, a fortuitous meeting and unfolding series of conversations with Kjersti Solbakken, Curator of Lofoten International Art Festival – LIAF 2024, revealed affinities between this aspect of The Kitchen’s history and LIAF 2024’s curatorial framework, which takes the Lofoten Line—a regional, wireless telecommunications system initiated in 1861—as inspiration to initiate a present-day, international network through which artists and institutions can transmit signals.21 Together, we began to conceptualize ways to explore crossovers between both institution’s models for distributing art and ideas, with the aim of simultaneously reanimating The Kitchen’s historical traditions of distribution and activating a new connecting point along the contemporary Lofoten Line. The ensuing cross-institutional dialogue among The Kitchen, LIAF 2024, and LIAF’s organizer the North Norwegian Art Centre has resulted in a range of outputs that will take shape between fall 2024 and winter 2025. As one facet of this multi-part exchange, the present article puts forth a focused study of Two Moon July as an artwork that not only is emblematic of The Kitchen’s traditions of distribution and circulation, but also self-reflexively examines many of the central questions related to the potential—and the stakes—of such dissemination processes.22

Still from Two Moon July, directed by Tom Bowes, 1986. Produced for The Kitchen by Carlota Schoolman. Courtesy of The Kitchen. Shown here: Brian Eno, Mistaken Memories of Mediaeval Manhattan; Robert Longo, Men in the Cities; Cindy Sherman, Untitled.

As a made-for-television special that renders The Kitchen’s activities on the small screen, Two Moon July extends from a lineage of the institution’s engagement with television that began at the time of its founding. In fact, the seeds of The Kitchen’s inception can be traced to television by way of the exhibition TV as a Creative Medium at the Howard Wise Gallery in New York City (May 17–June 14, 1969). The first exhibition in the United States to focus on the emergent practices of video art, TV as a Creative Medium identified the foundational ties between the new form of artmaking and the technology of television, featuring the two routes for usage that artists pursued at the time: to “use the television as art object, or to use the medium itself as art.”23The Kitchen’s co-founders Steina and Woody Vasulka cite their visit to the gallery as a defining moment in their personal practices and as a galvanizing inspiration to further their work in dialogue with other artists who they recognized as exploring similar interests as them.24 This awareness of a community with shared investment in the medium of video motivated the Vasulkas to envision and create The Kitchen as a space that could foster collective experimentation. In the years after The Kitchen opened, the interrelations between video art and television informed its range of programming, which included examples of both of the aforementioned uses. For instance, while installations such as one featuring Charlotte Moorman “lying on her back on a bed of television screens” deployed the object itself as an element of the work, performances of image-processed video manipulated television signals as the medium for making.25

With a sustained affiliation to television embedded in its DNA, The Kitchen was a natural candidate to extend its institutional support beyond presenting the aforementioned kinds of artworks and to begin experimenting with the transmission of art through television. The institution moved into this realm by becoming the installation site for the first cable line in the Soho neighborhood in February 1976 and initiating programming via public access cable—a system through which the public could register for free airtime on a first-come, first-served basis.26 The catalyst for The Kitchen to take this step came via the technological demands of a proposed project by artist Douglas Davis.27 In 1975, the artist conceived of a new performance that would involve live action as well as the broadcast of pre-recorded video in order to set up what he called an “active, two-way contact and interaction with the viewer on the other side of the set.”28 Davis initiated conversations with Manhattan Cable Television (MCTV) about introducing a cable line in Soho and with The Kitchen about acting as the location for the technology and the performance. The following year, MCTV installed one-way video and audio connections at The Kitchen, making it possible for the institution “to facilitate the simultaneous cablecasting of videotape and sound which are integral parts of [Davis’s] presentation.”29 As the first performance to use these connections, Davis’s piece Three Silent and Secret Acts took place on February 22, 1976, at The Kitchen and simultaneously was cablecast on one of MCTV’s public access channels. The pioneering event—“the first cablecast with a ‘live’ site in Soho”—was notable not only in modeling a new form of performance transmission at The Kitchen, but also in sparking interest among a group of film and art organizations to explore the possibilities of cable.30

Following Three Silent and Secret Acts, The Kitchen joined with over two dozen other Soho-based film and art organizations to form Cable Soho—a conglomerate that collaborated with MCTV in the further development of technologies and that began to program broadcasts of works of video art and cablecasts of live performances to a viewership of “over 80,000 Manhattan Cable Television subscribers.”31 However, differences in opinion among the members of Cable Soho quickly brought to light fundamental questions about the motivations of and priorities for transmitting art over television. According to artist Jaime Davidovich, one of the members of Cable Soho’s original board of directors, the internal debate centered on whether their programming should focus on live cablecasts of member organizations’ planned activities, or whether it could include new programs made for television—a variation of the question of whether to present art on television or to encourage the creation of television as art.32 Such disagreements caused the original organizational structure to dissolve after less than a year, at which point Davidovich renamed the initiative Artists’ Television Network (ATN) and took over as its President. While The Kitchen did not remain formally involved after this shift, the institution’s initial participation in the collective endeavor of Cable Soho laid the groundwork for the next phases of its experimentation with television programming.33

By 1978, The Kitchen redoubled its efforts with television along the lines of Cable Soho’s second route by beginning to introduce program frameworks that facilitated the production of new art for television. Coinciding with its decision to focus on commissioning work, the institution expanded its horizons outside public access cable and into the realm of public broadcast—a form of transmission that public broadcasters such as PBS operate through curated and administered program structures.34 Initiated through the joint efforts of The Kitchen’s Executive Director at the time, Mary Griffin (then Mary MacArthur), and its Associate Director for Television Programming, Carlota Schoolman, this new area of production support intended to fill what they perceived as a dearth in institutional support for artists creating work for broadcast in non-documentary forms.35 The movement into broadcast additionally reflected what the institution described as a converging set of conditions that made it appealing to both artists and audiences to test the possibilities of art on television within a wider sphere: “As television audiences have become more aware of artists such as [Philip] Glass, [Laurie] Anderson, and video pioneer Nam June Paik, artists have conversely become more interested in the broadcast medium.”36 With its commissioning endeavors, The Kitchen evolved from its role as presenter and programmer into that of television producer—a position that involved not only facilitating the creation of new works, but also liaising with public broadcasters to arrange distribution of the finished pieces. The first two artists MacArthur and Schoolman commissioned were Robert Ashley, whose seven-part opera for television, Perfect Lives (1978–1983) had its broadcast premiere in 1984 via Great Britain’s public broadcaster Channel Four, and Joan Logue, whose profiles of artists such as John Cage and Meredith Monk in the series 30 Second Spots: Television Commercials for Artists (1982) aired in varying public broadcast contexts, including as part of an episode of the inaugural season of the Walker Art Center-produced show Alive from Off Center on PBS in 1985.

Following its first two broadcast productions, The Kitchen received a $100,000 grant in 1984 from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting to support the creation of an hour‑long television special called The Kitchen Presents, to be produced by Schoolman.37After inviting Bowes to be the director and working with him on the program, Schoolman recognized an opportunity to extend The Kitchen’s efforts, as she articulated in a letter to a colleague at PBS in January 1985: “The more we work on it, the more it seems to become a pilot—there are so many threads to develop into future shows. With this in mind, we have asked NEA [the National Endowment for the Arts] to help us produce a series...”38 Formalizing the vision for The Kitchen Presents as an ongoing broadcast initiative in the referenced funding application, the institution described the series as a “cultural variety show” that aimed to “inspire regular viewing while bringing to television a whole field of contemporary art which is often overlooked by the broadcast medium.” Each episode of the series would “integrate video, music, dance, performance, and object work into a one hour format of seamless vignettes,” woven together through a rotating director’s use of “different conceptual devices to unite the presentation of disparate material.”39

The institution’s motivations for the progression from producing individual artists’ works for television toward establishing an overarching framework can be understood as practical in part, as this shift created opportunities for sustainability, such as the option to fundraise for multiple episodes at once.40 In another sense, The Kitchen’s interest in a serialized variety show can be seen as a response to the evolving media landscape in the early 1980s, when new types of shows and networks were emerging that relied on compilation frameworks to bring varied forms of culture onto television, from music videos to film and performance to comedy. Such programs included several created by artists and art institutions for both public access and public broadcast channels that customized the variety show style to their own avant-garde purposes, such as the aforementioned Alive from Off Center (1985–1996), which aired nationally on PBS, and the earlier precedents of Davidovich’s The Live! Show (1979–1984) for ATN and Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party (1978–1982), which aired on public access in Manhattan.41 Additionally, a number of commercial endeavors mirrored the same multi-act, multi-genre approach, as The Kitchen alluded in its NEA application: “It is imperative that we seize the opportunity laid by the ground-work of such programs as Saturday Night Live, M-Tv [sic] and Night Flight. These shows have prepared the audience for innovative format, and this same audience is now demanding challenging content. This is the type of material and format The Kitchen is in a position to offer.”42 Statements such as this suggest that The Kitchen’s understanding of broadcast’s potential had progressed away from its early-1980s description of television as a “new theatre for [artist’s] work”: rather, by the middle of the decade, the institution came to value the possibilities for made-for-television artworks to reprogram mainstream media references and formats to avant-garde ends.43

Still from Two Moon July, directed by Tom Bowes, 1986. Produced for The Kitchen by Carlota Schoolman. Courtesy of The Kitchen. Shown here: Molissa Fenley; Brian Eno, Mistaken Memories of Mediaeval Manhattan; Cindy Sherman, Untitled.

In the preceding section, I charted The Kitchen’s sustained involvement with television over its first decade and a half of operations, beginning with its founding impetus to support the creation and presentation of nascent forms of video art, including those that used television as object or medium, through to its experiments with programming for public access cable, and into its efforts as a television producer to commission new artists’ works for broadcast. What emerges through this trajectory is a sense of how the institution’s shifting program formats progressed in their focus: from art about television, to art on television, to work that takes up television as a form of art.44 Situated within this institutional history, Two Moon July marks an inflection point in what I suggest is the third phase of The Kitchen’s efforts with television, when its development inspired the institution to formalize The Kitchen Presents as a sustainable broadcast program series whose very framework—the established televisual format of a cultural variety show—would create space for directors and artists to reflect on and experiment with the potential for television to operate as art in the mid-1980s, during a period defined by an increasing array of crossovers between the art world and media.45 With Two Moon July, director Tom Bowes models one approach to examining television’s relationship with art that takes The Kitchen’s own programmatic activities as a starting point, turning the camera on the institution in order to consider its history of engagements with the small screen. Through this lens, the special presents to at-home audiences a dramatized portrayal of the making of an event that at once renders an image of the institution’s efforts realizing live performances in its Soho loft and offers a glimpse of the institution stepping into its reimagined role as a television producer and utilizing its programming space as a sound stage. Stemming from Bowes’s uniquely embedded position as a former staff member, the work illuminates the nature of The Kitchen’s longstanding television programming traditions by underscoring how the institution’s evolving efforts in this terrain allowed it to express and advance a number of the core principles that inspired its formation as a physical space. Two Moon July goes on to bring this survey of the institution’s past into the contemporary moment of its making, offering self-reflexive commentary on the extent to which the institution’s pursuits of such guiding interests carried added stakes within a shifted cultural landscape.

Returning to the initial moments of Two Moon July, the opening sequences reveal an extended meditation on the positionality of and relationships between several of the special’s references. In its progression from the mysterious image of the skyline at dusk to the descriptive views of The Kitchen’s interior and the layered image of the video installations’ television screens on the broadcasting screen, the work introduces the specific site of The Kitchen’s loft through a dynamic interplay between the interior space, the city outside, and recorded images of both. With this triangulation, the work evokes one of the institution’s foundational practices: positioning itself in relation and response to other contexts and aspects of culture. At the time of its founding, The Kitchen was one of a growing body of spaces, largely based in downtown New York, that set out to address perceived gaps in the programming and policies of traditional institutions. These emergent endeavors, which came to be known as alternative spaces, took on varying forms in the interest of creating conducive conditions under which artists could produce and present forms of art that existing museums and galleries had not yet welcomed into their programming, such as work in nascent mediums.46 In forming The Kitchen, the founding collective both addressed the reality that video artists did not have outlets to show their work within the established sphere of art institutions and developed a series of physical and programmatic structures that enabled the institution to meet these artists’ specific needs, including by outfitting the space with necessary equipment like cameras and screens and establishing weekly program series such as Open Screenings during which artists could share new works with their peers.47 Additionally, the collective was committed to generating a context that allowed for a kind of live video presentation that entailed an encounter between artists and audiences, which they accomplished by adopting the model of a theater with “the concept of the audience coming in, and a presentation beginning and ending,” as co-founder Steina Vasulka described it.48 Though many of its structures necessarily evolved throughout its first years to accommodate institutional shifts in areas including disciplinary scope, funding, and artist and audience demand, The Kitchen maintained a central commitment to serving as an institutional context that was, in the words of subsequent Executive Director Robert Stearns, “uniquely suited to handle the special and changing requirements” of “the contemporary art idiom.”49

Complementing The Kitchen’s founding interest in generating a customized setting in which specific forms of contemporary art could flourish was its desire to foster relationships between avant-garde practices and other aspects of culture. Through their decision to situate The Kitchen initially within Mercer Art Center, the collective expressed this guiding aim by placing the nascent space in proximity to a varied set of theaters that presented everything “from political cabaret to traditional theater to experimental work in any new artistic form.”50 This aspect of the complex held particular appeal for Woody and Steina Vasulka, who described it as “culturally and artistically a polluted place. It could do high art and it could produce average trash.”51 By virtue of its heterodox positioning, The Kitchen established itself as an institutional home for what Woody Vasulka called “an undefined creative milieu” that drew from a range of cultural associations, from high to low and mass to marginalia.52

The Kitchen’s move in the mid-1970s into the realm of transmitting art through television represented an opportunity for the institution to extend its investment in establishing alternative settings for art outside existing institutional structures. As a mode of distribution that circulates content directly into the homes of audiences, television offered a new realm for encounters with artworks—a realm that notably fell outside the parameters of both traditional institutions and alternative spaces. In engaging with the platform of television, the institution additionally gained access to wider groups of viewers, allowing it to further its investments in bringing artists and audiences into contact. The institution’s programmatic shift from cablecasting to broadcasting enabled it to connect with progressively larger audiences across broader geographies, moving from public access cable’s transmission within the local region of Manhattan into broadcast’s reach across a national and/or international radius (dependent on distribution arrangements). As such, The Kitchen’s decision to broadcast Two Moon July—a program that unfolds within its Soho loft space—as the pilot episode of The Kitchen Presents emphasizes the institution’s intention to create opportunities for audiences from a wider area well outside the city to experience its New York-based activities.

For viewers watching Two Moon July on a television screen, the moment at which the camera zooms out to reveal the setting of The Kitchen’s loft is a turning point in illuminating the work’s commentary on the interrelations of different contexts. Presenting the institution’s physical space as a televisual image, the scene brings together the institutional setting that The Kitchen created to present art outside of museums and galleries and the platform of television that it explored as an extension of this alternative. The act of visualizing the screen as an alternative space for art calls attention to the ethos that unites the two distinct contexts.53 At the same time, the merged institutional/televisual frame underscores differences in the kinds of art making, presentation, and reception each individual context supports. For instance, in the case of Two Moon July, the made-for-television rendering of an event happening in real time and space makes explicit the ways televisual modes allow directors and artists to control a viewers’ experience of a performance more precisely than they would within a physical institution—as Bowes does in moments like when he frames the expressive reach of Bill T. Jones’s arms during a dance sequence in parallel with the positions of the individuals frozen mid-gesture in Robert Longo’s lithographs, which are displayed on the wall behind.54

By situating the visual art objects, performances, and video excerpts that it showcases within the defined site of The Kitchen, Two Moon July offers a counterproposal to the ways art had begun to circulate in the media throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s. A confluence of factors, including artists working with greater fluidity between art and pop culture contexts and media outlets increasingly turning their attention toward artists as creators, led to the proliferation on television of work by many creative practitioners who had developed their careers in avant-garde spaces. Music videos for songs by performer/musicians like Laurie Anderson and David Byrne, others directed by video artists such as John Sanborn and Kit Fitzgerald, and MTV Art Breaks by artists such as Dara Birnbaum were just a few such forms made by artists who also appeared in The Kitchen’s television special.55 While the inclusion of such artists in mainstream media contexts made them more visible, it introduced viewers to their work according to the defining terms of television transmission: in the words of artist Judith Barry, “television reduces all individual programming to the medium that it is; in its endless flow, context is everything.”56 As a result, many at-home audiences solely encountered these artists’ activities in association with the examples of pop culture that their work appeared alongside on broadcast networks, without the opportunity to regard their efforts in relation to the avant-garde practices with which they remained in dialogue.57 In an act of reassigning context, Two Moon July intervenes in the televisual flow to reattach artists’ works to the setting of the alternative art space. In so doing, the work gestures at the dual significance institutions like The Kitchen held in creating conditions to foster artistic experimentation and in pioneering strategies to animate television’s capacities as a context for art.

When considered in relation to The Kitchen’s programmatic investments, Two Moon July’s act of centering its institutional site comes into focus not as a means of negating the realm of television’s potential, but rather as a reference to the ways the platform provided the institution a vehicle to further its originating aim of positioning itself in relation to a “polluted” spectrum of activities. Just as Mercer Art Center had been, the context of television was inherently contaminated by its affiliations—in this case, not only popular culture, but also commerce.58 Building on how The Kitchen’s previous experiments with cablecasting and broadcasting inserted artists’ contributions into the flow of diverse televisual content, Two Moon July ingrains within its very format as a multi-act special the institution’s commitments to placing wide-ranging forms of art in dialogue with one another and with popular culture. Bowes’s choice to take up the variety show framework additionally solidified a structural means of magnifying television’s characteristic flow within the program: the show acts as a container to unite a diversity of types of content under one banner, while simultaneously creating a microcosm of the channel-surfing experience, whereby a viewer jumps quickly between programs and commercials of widely varying type and tone.59 The Kitchen’s support of Two Moon July and its ensuing decision to adopt the variety show as the standardized model for the proposed continuation of The Kitchen Presents series reflects strategic interests, including the institution’s desire to make its programs legible in relation to mainstream ventures like MTV, Saturday Night Live, and Night Flight that utilized this same kind of multi-act sequence, as the institution itself referenced in the grant application mentioned in the previous section. On another level, the institution and the director’s embrace of a populist format suggests an effort to produce programming that would draw in would-be viewers by capturing their attention and holding their interest: the longstanding and recognizable televisual form is characterized by a “‘something-for-everyone’ olio format” that “broadly [appeals] to the diverse tastes of television’s national public.”60In this respect, the familiarity of the overarching form represented an accessible entry point for television audiences to connect with the segments’ avant-garde content—a pairing that aligns with both what the director termed as his personal interest in making “the piece somewhat edible and somewhat inedible” and with the promise of The Kitchen Presents being categorized as an “arts and entertainment” program.61

As Two Moon July progresses from its opening scenes into a sequence of artistic vignettes, the special begins to inhabit the style of a variety show, signaling this shift through the voice of the technician whose call to “get settled in” marks the first of a series of moments in which The Kitchen’s staff take up the position of the program’s de facto hosts. In tandem with the work’s strategy of centering The Kitchen as host site in order to convey commentary on television’s potential as a context for art, the piece introduces an additional layer of self-reflexive questioning by using the behind-the-scenes interludes to frame the institution’s internal, running production dialogue as a structuring principle that can redirect the standard aims of the televisual format. Establishing the ways in which the staff’s exchanges speak on multiple levels, the opening call evinces a dual nature as both an instruction to performers to take their places for the evening’s event and an invitation to viewers to take up their position as the at-home audience. Bowes’s choice of the program’s first act further specifies the message delivered to those tuning in. Moving forward from a final shot of the set-up activities within the loft, the image wipes to reveal Anderson at a microphone in the performance-ready space, intoning through a vocally processed persona she calls the “Voice of Authority”: “Good evening. Welcome to Difficult Listening Hour. The spot on your dial for that relentless and impenetrable sound of difficult music. So sit bolt upright in that straight-backed chair, button that top button, and get set for some difficult music.”62 Through the pairing of the institution-as-host and the artist’s opening directives, Two Moon July primes viewers for the nature of artworks that follow: with the knowing raise of an eyebrow, Anderson and The Kitchen posit that so-called difficult work can in fact be the substance of entertainment, offering a satirical rejoinder to what has been referred to as “the First Commandment of Broadcasting”—“‘appeal to the lowest common denominator.’”63

Giving expression to Anderson’s introductory premise, the unfolding sequence of excerpted works runs the gamut in style and form, from Molissa Fenley’s high-energy movement sequence Hemispheres to Philip Glass’s meditative performance of Mad Rush on piano to Vito Acconci’s brooding, black-and-white video The Red Tapes. While teasing the question of where on the spectrum between art and entertainment each work lands, Two Moon July holds true to The Kitchen’s defining range of interdisciplinary activities, described in one promotional text as a “collage of cultural multi-media crosstalk.”64 In tandem with the special’s siting within the institution’s loft and the staff’s part in narrating the evening, the programmatic range layers an additional aspect of institutional specificity into the customized variety show form. Through these acts of infusing one of the most popular televisual formats with directed references to The Kitchen’s institutional functions and avant-garde activities, the special calls attention to the extent to which the avant-garde has served for generations as what art historian Thomas Crow has called “a kind of research and development arm of the culture industry.”65 In this manner, Two Moon July adopts a metacritical relationship to television—both strategically operating within it and pointing outward toward the ways that the platform feeds off or connects to other areas of culture, asking: what would television culture of the mid-1980s have looked like if spaces like The Kitchen hadn’t helped to foster the kinds of artistic forms and genres that went on to circulate so widely over the airwaves?66

Still from Two Moon July, directed by Tom Bowes, 1986. Produced for The Kitchen by Carlota Schoolman. Courtesy of The Kitchen.

Still from Two Moon July, directed by Tom Bowes, 1986. Produced for The Kitchen by Carlota Schoolman. Courtesy of The Kitchen.

Echoing its opening scenes, Two Moon July ends with one final backstage glimpse of the crew talking, laughing, and lingering after the production has concluded. The screen fades to black, and the image of the cityscape at twilight reappears, with its enigmatic two moons reasserting their place in the sky. Returning to where it began, the special zooms out from The Kitchen’s interior world to the city outside—a shift in vantage that hints at the path the work itself follows as it transmits throughout New York and beyond over the broadcast airwaves. For at-home audiences, this moment of pause at the outset of the end credits places them in a position to reflect on the nature of this transmission. From this vantage, the viewer is poised to see the pair of moons in relation to the program they’ve just experienced as a visualization of the ways Two Moon July itself embodies an act of doubling: portraying The Kitchen’s onsite activities through a televisual mode, the special sends out an image of the institution that—like the second, smaller orb—not only bears traces of translation in its form, but also carries with it an aura of mystery as it hovers in a state between reality and fiction.67

When considering the viewers’ perspectives on the work, it is important to recall that many individuals would not have encountered The Kitchen before watching Two Moon July on television or via any of the other platforms through which it circulated, including as a featured work in a number of national and international film festivals and as a title available through independent distributor Pacific Arts Video. This detail still holds bearing as the work has continued to circulate through both art and non-art circuits into the present day.68 As such, the work entails heightened stakes of introducing audiences to the institution in the form of a doubled image delivered via a videotape-based mode that possesses the capacity to transmit across space and time. Extending the reading of Two Moon July as a metacritique of the televisual landscape that I put forth in the previous section, I propose that the work’s ability to function as a made-for-television cultural variety show, even as it reflects on that very form’s potential, imbues it with a “both/and” reasoning that inherently calls for a multiplicity of interpretations. When seen as a realization of this logic, the two different understandings of Two Moon July that I have cited in this article do not contradict one another, but rather engage with distinct aspects of the work: it can be understood both on the terms of the promotional video, which frames the special as a showcase of art on television, and according to my own evaluation of it as a self-reflexive survey of The Kitchen’s programmatic history and aims that Bowes conveys by using television as a form art. By the same token, I suggest that in conveying what programmatic materials referred to as an “impressionistic portrait” of The Kitchen, the special leaves room for viewers to form a varied range of conceptions about the institution at its center—a strategy that evokes the multiple different roles the space served as a site of programming, a hub for artistic community, an institutional player within the national and international arts landscape, and more.69 By inviting audience responses that pick up on any of these aspects, Two Moon July encourages a proliferation of unique understandings, thus underlining the extent to which the institution, like the artworks it has supported since its inception, evades straightforward categorization or description.

Two Moon July’s optimistic embrace of television as a platform that can foster such varied viewer engagements reflects the specter of possibility that hovered on the horizon at the time of its making in the mid-1980s, when The Kitchen advanced its experimentation with television programming. As evinced in the institution’s internal documents from this period, manifold motivations buoyed the special’s creation and inspired the articulation of The Kitchen Presents as a series: a recognition of television as a productive platform to expand audiences and institutional visibility, an investment in entering into dialogue with the era’s television programming, a belief that artworks could engage with television without diluting their artistic integrity, and a conviction that a series framework could create sustainability for these efforts.70 In subsequent years, however, the promise of television as a fertile, long-term programmatic context did not come to fruition: for varied practical and organizational reasons, the institution went on to create only one more episode in The Kitchen Presents series before diminishing its formalized investments in broadcast as an arm of its programming.71 When viewed in relation to this historical trajectory, Two Moon July transmits into the present as a time capsule preserving a utopian approach to utilizing television as a form of art at a unique moment in cultural history. Yet from an alternative perspective, as an artwork that is continually revitalized by its contemporary reception, the special carries an open-ended provocation to interrogate the relationships between artistic practice, institutional support, and mass media platforms—an invitation whose import only continues to gain relevance today.72

Click here to view Two Moon July. The work will be available for online viewing throughout the duration of LIAF 2024 (September 20–October 20, 2024).

The author would like to extend her appreciation to the Metode editorial board—particularly Ingrid Halland, Kjersti Solbakken, and Victoria Bugge Øye—and to Ian Wallace and Fia Backström for invaluable feedback on drafts of this article.

In Memoriam: This article is dedicated to Tom Bowes.

1 The soundtrack is an excerpt from Brian Eno, “Mistaken Memories of Mediaeval Manhattan” (1980). In Eno’s words, the album from which this song comes is characterized by “quite a disturbed landscape: some of the undertones deliberately threaten the overtones, so you get the pastoral prettiness on top, but underneath there’s a dissonance that’s like an impending earthquake." Don Watson, “Man Out Of Time,” Spin, May 1989, http://music.hyperreal.org/artists/brian_eno/interviews/spin89a.html.

2 Quotation from Two Moon July, directed by Tom Bowes (produced by Carlota Schoolman for The Kitchen, 1986), 4:38.

3 The Kitchen, press release for premiere of Two Moon July on PBS on September 11, 1987, The Kitchen Archives, TKC20; “The Kitchen Presents: Two Moon July, Promotional Campaign,” final narrative report, enclosure in Barbara Tsumagari, letter to Anna Satariano, Corporation for Public Broadcasting, August 27, 1987, The Kitchen Archives, TKC20. The Kitchen was responsible for securing air time on PBS’s affiliate networks: “The Public Broadcasting System (PBS) has accepted Two Moon July for national broadcast in the upcoming season … PBS provides programming for a network of 317 independent affiliates serving each state as well as every major metropolitan area. Because each affiliate makes independent programming decisions, The Kitchen and PBS staff will coordinate a marketing campaign designed to encourage a significant number of affiliates to pick up the program at the time of its national airing.” The Kitchen Center for Video, Music, Dance, Performance and Film, proposal for “The Kitchen Presents—Two Moon July,” submitted to JVC Company of America, September 30, 1986, enclosure in Susan A. Fait, letter to Caren Tauber, Shaw and Todd, Inc., September 30, 1986, The Kitchen Archives, TKC20.

4 “Woody Vasulka Timeline,” Vasulka Archive, https://www.vasulka.org/archive/Publications/FormattedPublications/BUFLWV.pdf. The carpenter Andres Mannik located the space in the Mercer Art Center and helped the Vasulkas to build out the space. See Woody and Steina Vasulka, Don Foresta, and Christiane Carlut, “A Conversation, Paris, Saturday 5, December 1992,” Vasulka Archive, https://www.vasulka.org/Kitchen/essays_carlut/K_CarlutConversation.html.

5 By 1985, the institution had outgrown the capacities of its Soho loft space, prompting it to relocate in 1986 to a three-story building in Chelsea outfitted with two separate theater/presentation spaces, a dedicated video viewing room, and administrative offices. Two Moon July is the last artistic event staged in the loft at 484 Broome Street before the move, making it a significant record of The Kitchen’s programming within the space that housed the institution during its seminal early years.

6 Maria A. Lisella and Jon Ciner, “No Kitsch in the Kitchen,” The Villager, June 15, 1978, The Kitchen Archives, TKC20.

7 The use of the variety show format to introduce avant-garde art to television audiences finds precedent in variety shows from the 1940s and 1950s that engaged the subject of modern art. See Lynn Spigel, TV by Design: Modern Art and the Rise of Network Television (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 19–20 and 44–47.

8 Press release for premiere of Two Moon July on PBS on September 11, 1987.

9 Two Moon July additionally includes music excerpts by Brian Eno, Philip Glass, and Arto Lindsay and the Ambitious Lovers.

10 Press release for premiere of Two Moon July on PBS on September 11, 1987.

11 The cast includes Tim Carr, Anne DeMarinis, Howard Halle, Bob Wisdom, and Michael Zwack.

12 The cast’s actual roles on staff included: Howard Halle, Gallery and Performance Curator; Tim Carr, Special Projects; Anne DeMarinis, Production and Music Curator; Bob Wisdom, Music Curator; and Michael Zwack, Production Management. Note that many staff members moved through different roles over time; this list is non-exhaustive of the roles each individual held.

13 Even after stepping down from his staff role, Bowes remained affiliated with The Kitchen by joining the Board of Directors in 1984 and serving in that capacity for over ten years.

14 Notable programs Bowes organized while working at The Kitchen include video screenings such Return/Jump: A Video Retrospective, 1979–1982, October 10–17, 1982; video programs for distribution including Video/Music 1 and 2, 1982; and organizing the video program for Aluminum Nights: The Kitchen’s Birthday Party and Benefit, June 14–15, 1981.

15 “While television is often seen as the postmodern medium par excellence, after the mid-1970s, high and low—at least on broadcast television—became increasingly bifurcated so that networks narrowed their business goals, leaving arts programming largely to cable, museum, videos, PBS and other ‘narrowcast’ venues.” Spigel, TV by Design, 18.

16 The Kitchen, Two Moon July 1986 promo trailer, 1986, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-yWYNmy2xNg, 00:59.

17 Ibid., 00:01.

18 For instance, one internal document alludes to the work’s engagement with television as a form of art by describing it as an “hour long program which explores the dynamics between television and live contemporary performance.” Proposal for “The Kitchen Presents—Two Moon July,” submitted to JVC Company of America, September 20, 1986.

19 Past initiatives at The Kitchen have looked at isolated instances of program examples from some of these program areas, but none have treated this suite of programs synthetically. For examples of programs that have addressed The Kitchen’s television productions, see “Carlota Schoolman and Stephen Vitiello In Conversation,” March 11, 2021, online at onscreen.thekitchen.org; and “Interviews with the Cast and Crew from Robert Ashley’s Perfect Lives,” Montez Press Radio, June 8, 2023. For an example of a program that addressed The Kitchen Touring, see the multipart program Julius Eastman: That Which is Fundamental, curated by Tiona Nekkia McClodden with Katy Dammers and Matthew Lyons, January 19–February 10, 2018 at The Kitchen. This project included reference to The Kitchen Touring in the exhibition portion “A Recollection.”

20 The Kitchen Archives in New York include ephemera and audio/visual documentation from 1971 to the current day; The Kitchen’s Video Collection (videos that the institution offered for exhibition and broadcast through its international video distribution program); and institutional papers such as grant applications, correspondence between staff and external parties, curatorial files, and education and outreach files. As of fall 2024, The Kitchen is in the midst of a large-scale project to catalog and preserve the contents of these collections, spearheaded by The Kitchen’s Archivist, Alex Waterman. Members of the public can make appointments to view the physical contents of the Archives in New York while this is underway, but currently there is no comprehensive digital database to allow individuals to search the collection (selected materials are available on the institution’s websites thekitchen.org/on-file/ and https://archive.thekitchen.org/). In addition to The Kitchen Archives in New York, the Getty Research Institute (Los Angeles, CA) holds a collection of the institution’s videos and records from 1971 to 1991: for more on this collection, see https://www.getty.edu/research/special_collections/notable/the_kitchen.html.

21 Thank you to Ariana Tiziani, Art and Culture Advisor, Royal Norwegian Consulate General in New York, for facilitating the introduction to Kjersti Solbakken.

22 The cross-institutional exchange has resulted in additional outputs, including the co-commissioning by The Kitchen and LIAF 2024 of a new work by artist Wong Kit Yi. The artist’s work will premiere at LIAF 2024 in Lofoten, Norway (September 20–October 20, 2024), and then be featured in the exhibition Lines of Distribution at The Kitchen’s temporary location in Manhattan, known as The Kitchen at Westbeth (November 21, 2024–January 18, 2025). Lines of Distribution also will feature contributions from three other artists featured in LIAF 2024—Viktor Bomstad, Elise Macmillan, and Kameelah Janan Rasheed—creating occasion for them to extend their work at The Kitchen while reflecting on the extent to which the meaning and associations of their projects evolve as they circulate through different institutional and cultural contexts. Two Moon July has been a central reference and source of inspiration throughout the dialogues among our institutions. Bowes’s work will be featured in both LIAF 2024, where it will be screened as part of a program with KINOBOX, and Lines of Distribution, which will include archival materials related to the special.

23 Richard Skidmore, “TV as Art,” https://www.eai.org/user_files/supporting_documents/TVasArt.pdf. For more on TV as Creative Medium, see Howard Wise Gallery, exhibition brochure for TV as Creative Medium, May 17–June 14, 1969, https://www.eai.org/user_files/supporting_documents/tvasacreativemedium_exhibitionbrochure.pdf. For more on the relationship between television and video, see David Antin, “Video: The Distinctive Features of the Medium,” in Video Art: A History, ed. Barbara London (New York: Electronic Arts Intermix, 1976). For a comprehensive discussion on video art, see Ina Blom, The Autobiography of Video: The Life and Times of a Memory Technology (New York: Sternberg Press, 2016).

24 Lenka Dolonova, A Dialogue with the Demons of the Tools: Steina and Woody Vasulka (Brno: Vašulka Kitchen Brno: Center for New Media, 2021), 57.

25 Tom Johnson, Village Voice, July 6, 1972, The Kitchen Archives, TKC20.

26Public access originated in Manhattan in 1970, when the borough “became the first major metropolitan area to sign a franchise agreement with a cable company. The purpose of wiring the city was to improve color reception of the network stations—not to offer original programming. But activists like George Stoney, Theodora Sklover, and others saw a new potential in the technology. With added channels on the dial, New York could diversify programming and open up the field of television production to the general public. Their successful campaign led to the Public Access Cable television mandate in the 1970s franchise: two channels would offer free, (nearly) uncensored airtime, first-come, first-served.” Leah Churner, “Un-TV: Public Access Cable Television in Manhattan—an Oral History,” February 10, 2011, Museum of the Moving Image: Moving Image Source, https://movingimagesource.us/articles/un-tv-20110210.

27 Douglas Davis is an artist whose previous work with video focused in large part on questions of the “anonymity and passivity of television production and reception.” For more on Davis, see Electronic Arts Intermix, “Douglas Davis: Biography,” https://www.eai.org/artists/douglas-davis/biography.

28 Jody McMahon, “The Coming of Cable Soho,” Videography, June 1977, The Kitchen Archives, TKC20.

29 Robert Stearns quoted in McMahon, “The Coming of Cable Soho.”

30 Three Silent and Secret Acts “was a multiple-audience, multiple-time (live and cable television) performance” that involved the interplay between a video tape capturing “an initial realization of the performance” the night before, a live performance at The Kitchen, and a simultaneous performance by two performers at the MCTV studio elsewhere in Manhattan. See Douglas Davis in The Kitchen Yearbook: 1975–1976 (New York: The Kitchen, 1977), 20.

31 Robert Stearns, “Preface,” in The Kitchen Yearbook: 1975–1976. Other organizations participating in Cable Soho included Anthology Film Archives, Artists Space, the Association of Independent Video and Film Makers, Cable Arts, Electronic Arts Intermix, Franklin Furnace, Global Village, Institute for Art and Urban Resources, Manhattan Cable Television, the Soho Artists Association, the Soho Performing Artists Association, and Young Filmmakers-MERC. McMahon, “The Coming of Cable Soho.”

32 Churner, “Un-TV.”

33Artists’ Television Network (ATN) focused on programming that featured presentations of works that were “conceived as television rather than as document of an activity or event.” JoAnn Hanley, “Introduction,” in the exhibition catalogue for Jaime Davidovich: The Live! Show, American Museum of the Moving Image, 1989, http://movingimagesource.us/files/the_live_show.pdf. For more on ATN, see the Artists’ Television Network Collection, Iowa University Libraries, https://www.lib.uiowa.edu/sc/ltfs/atn/. The Kitchen featured ATN in its programming in a variety of ways throughout the networks’ existence, including hosting a program of daily screenings on the occasion of the first anniversary of Soho Television (one of ATN’s initiatives) from December 14 to 23, 1978, and featuring ATN programming in Video Viewing Room programs, including as part of “Cable Review Lounge” on February 21, 1984.

34 This article focuses primarily on The Kitchen’s cablecasting and broadcasting initiatives between 1971 and 1985. Other programs that engaged with television in this era that are not discussed here include screenings of works of guerrilla television; a range of video programs that juxtaposed video art with commercial television; curated, thematic programs of video art tailored for distribution on cable; and discursive programs addressing issues related to television’s role in society and artmaking, including the symposium Television/Society/Art, October 24–26, 1980.

35 Mary Griffin, “Interviews with the Cast and Crew from Robert Ashley’s Perfect Lives,” Montez Press Radio, June 8, 2023. Schoolman’s own background with television likely had a part in making the institution’s move into the terrain possible: she had previously served as The Kitchen’s Video Director from 1974–1977, and prior to that, worked with the Sloan Commission on Cable Communications from 1970–1971 and with Experiments in Art and Technology in 1971 on programs broadcasting artists’ works on public television prior (Carlota Schoolman Oral History, The Kitchen Archives). For more on the support of documentary practices, see Robin White, "Great Expectations: Artists’ TV Guide," Artforum 20, no. 10 (Summer 1982): “Despite the thrill of reaching such a large audience, artists’ enthusiasm for public television has waned because the Corporation for Public Broadcasting has given much more support to independent documentary producers than to artists.” For more on program support for artists’ residencies in public television throughout the US, see Kathy Rae Huffman, “Video Art: What’s TV Got to Do With It?,” in Illuminating Video: An Essential Guide to Video Art, ed. Doug Hall and Sally Jo Fifer (New York: Aperture, 1990), 81–90, esp. 86.

36 The Kitchen, National Endowment for the Arts Proposal to Programming in the Arts: To produce four half-hour programs in the television series The Kitchen Presents, January 1985, The Kitchen Archives, TKC20.

37 Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) Program Fund News, Vol. 4/No. 2, May 1984, The Kitchen Archives, TKC20. CPB is a private, nonprofit corporation created by the U.S. Congress in 1967 to steward the federal government’s investment in public broadcasting. For more on CPB, see https://www.cpb.org/.

38 Carlota Schoolman, letter to Cathy Wyler, PBS, January 16, 1985, The Kitchen Archives, TKC20. Note that at the time of this article’s publication, it is unknown whether Schoolman invited Bowes to participate in The Kitchen Presents with an open-ended invitation to develop the program, or with a directed ask to work in a specific form.

39 The Kitchen, National Endowment for the Arts Proposal, 1985. Note that at the time of this article’s publication, it is unknown if application was awarded.

40 For instance, The Kitchen’s application to the NEA requested funding for four episodes of the series. Ibid.

41 This is a non-exhaustive list of artist-produced programming for public broadcast. The Kitchen regarded Alive from Off Center as a peer program and was attuned to its producers’ activities. As previously noted, Joan Logue’s 30 Second Spots, produced by The Kitchen, aired in Alive’s first season. Additionally, The Kitchen was in dialogue with the Alive producers about featuring Two Moon July in an episode of the series. Melinda Ward, Executive Producer of Alive from Off Center, letter to Carlota Schoolman, 22 November, 1985, The Kitchen Archives, TKC20. In a funding proposal to JVC, The Kitchen names Alive from Off Center as a point of comparison for Two Moon July’s projected reach: Alive garnered 1.4 million audience in its first season. Proposal for “The Kitchen Presents—Two Moon July,” submitted to JVC Company of America, September 20, 1986. For more on Davidovich’s The Live! Show, see Ian Wallace, “TV TV,” in Jaime Davidovich: Museum of Television Culture (New York: Churner and Churner, 2013). For more on Alive from Off Center, see Lauren Mackler, “Alive from Off Center,” Walker Reader, August 31, 2022, https://walkerart.org/magazine/lauren-mackler-alive-from-off-center. For more on O’Brien’s TV Party, see Gavin Butt, “Welcome to the TV Party,” in Take It or Leave It: Institution, Image, Ideology, ed. Johanna Burton and Anne Ellegood (Los Angeles: Hammer Museum, 2014), 216–221.

42 The Kitchen, National Endowment for the Arts Proposal, 1985. The launch dates for these references are as follows: Saturday Night Live, 1975; MTV, 1981; Night Flight, 1981.

43 The Kitchen, “Briefly, The Kitchen’s History,” internal document Spring 1981, The Kitchen Archives, TKC20. The Kitchen’s progression toward an interest in repurposing mainstream references can be understood in relation to strategies of appropriation that were prominent in the contemporary art practice in the 1980s. For more on this era, see Burton and Ellegood, Take It or Leave It and Gianni Jetzer, ed., Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s (Washington, D.C: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden/ Rizzoli Electa, 2018).

44 Note that this progression within The Kitchen’s programming was not linear: examples of other forms also appeared in earlier phases or persisted even as focus shifted.

45 For more on the art and pop culture crossover, see Butt, “Welcome to the TV Party,” 219; Jetzer, Brand New; Roselee Goldberg, High & Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture: Six Evenings of Performance (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1990). For more on art and television, see Linda Furlong, “Getting High Tech: The ‘New’ Television,” The Independent, Vol. 8, March 1985; Judith Barry, “This Is Not A Paradox,” in Illuminating Video: An Essential Guide to Video Art, ed. Doug Hall and Sally Jo Fifer (New York: Aperture, 1990), 249–257.

46 Other alternative spaces were formed with different aims, such as the goal of confronting issues of representation by creating space for artists who experienced exclusionary racism and sexism. Examples of such institutions include A.I.R. Gallery, a co-op gallery formed in 1972 to support female artists, and Just Above Midtown (JAM), a commercial gallery founded by curator Linda Goode Bryant in 1974 to provide exhibition opportunities for Black artists. For more on alternative spaces, see Julie Ault, Alternative Art New York: 1965–1985 (New York: Drawing Center; Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002). For more on the institutional practices of alternative spaces in relation to the strategies of Institutional Critique, see Alison Burstein, “Institutional Critique, Alternative Spaces, and New Institutions: A Genealogy,” 2018, Columbia University master’s thesis.

47 For more on the Open Screenings series, see Millennium Film Workshop: Open Screenings, June 30, 2023, https://thekitchen.org/on-screen/open-screenings/.

48 Jud Yalkut, “The Kitchen: An Image and Sound Laboratory: A Rap with Woody and Steina Vasulka, Shridhar Bapat and Dimitri Devyatkin,” Part Three of Open Circuits: The New Video Abstractionists, April 1, 1973, Vasulka Archive, https://www.vasulka.org/Kitchen/K_Audio1.html. The centrality of the audience to the Vasulkas’ vision is underscored in the name they originally appended to The Kitchen: LATL (Live Audience Test Laboratory) (ibid.)

49 Stearns, “Preface,” in The Kitchen Yearbook: 1975–1976.

50 The Mercer Arts Center Brochure, c. 1971, Vasulka Archive, https://www.vasulka.org/archive/Kitchen/KBR/KBR1.pdf.

51Steina and Woody Vasulka, “Origins of The Kitchen,” 1977, Vasulka Archive, https://www.vasulka.org/Kitchen/KRT.html. For example, in an oft-cited example, the glam rock band the Magic Tramps performed at Mercer Art Center. The Kitchen’s founding interest in artistic “pollution” is also reflective of the range of influences that the Vasulkas embraced in their own practices: “We were interested in certain decadent aspects of America, the phenomena of the time: underground rock and roll, gay theater and the rest of that ‘illegitimate’ culture. In the same way we were curious about more puritanical concepts of art inspired by McLuhan and Buckminster Fuller.” Vasulkas, “Origins of The Kitchen.”

52 “Woody Vasulka Timeline.” The institution further ingrained its commitments to creating dialogue among these varied forms through its programmatic choices. The institution’s music program evinced prominent examples in its early years, such as a 1975 performance by the Modern Lovers billed as “A Rock and Roll Show” that represented one of musician and then-Music Director Arthur Rossell’s seminal acts of introducing popular music alongside the institution’s more common lineup of new music artists. For more, see Sarah Cooper, Expanding Experimentalism: Art and Popular Music at the Kitchen in New York City, 1971–1985, CUNY Hunter College master’s thesis, 80. Thank you to Victoria Bugge Øye for noting the relevance of mass/marginalia.

53 In calling television an alternative space, I draw from Gwen Allen’s analysis that in the 1960s and 1970s, artists’ magazines “became an important new site of artistic practice, functioning as an alternative exhibition space for the dematerialized practices of conceptual art.” I suggest that television can be regarded in the same way as an alternative space for video art in the 1970s and 1980s. Gwen Allen, Artists’ Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 1.

54Bill T. Jones in Two Moon July, directed by Tom Bowes (produced by Carlota Schoolman for The Kitchen, 1986), 22:09–22:12. The lithographs on view are from the series Robert Longo, “Men in the Cities,” 1979–1983.

55Art Breaks was a series on MTV in 1985 in which “artists presented their artistic brands in short clips.” Jetzer, Brand New, 75.

56 Barry, “This Is Not a Paradox,” 257.

57 “In a market where money buys effects and the technology allows for few shortcuts, the ‘art’ on MTV is virtually indistinguishable from other programming produced by artists.” Barry, “This Is Not a Paradox,” 251. “While sometimes thought as having disrupted the mainstream with images of the avant-garde, the original Art Breaks are another testament to the open channels between art and the world of commerce.” Jetzer, Brand New, 75.

58 For more on the relationship between television, commodity, and network, see David Joselit, Feedback: Television Against Democracy (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), esp. 15–26.

59 Through this lens, the video art interludes in Two Moon July can be seen as stand-ins for commercials, interspersed between the segments of the live recordings. This gesture nods to the ways that some video artists had begun to create advertisements at the time, inverting the practice to reinsert video art in its original form.

60 Spigel, TV By Design, 44. The Kitchen voiced this logic in the January 1985 NEA application, stating “Those viewers not familiar with the avant-garde will be surprised by its liveliness, range, and vision; those already acquainted will welcome the opportunity to see this work in their own homes.” The Kitchen, National Endowment for the Arts Proposal, 1985.

61Tom Bowes, interview with the author, June 5, 2023. As mentioned in the previous section, Jaime Davidovich’s The Live! Show should be seen as a key predecessor to Two Moon July. In the winter of 1979–80, Davidovich produced an interactive program to survey viewers on their preferences: “His research confirmed his ideas that a variety-show format was most likely to keep people tuned in.” White, “Great Expectations.”

62Laurie Anderson in Two Moon July, directed by Tom Bowes (produced by Carlota Schoolman for The Kitchen, 1986), 4:54. Anderson uses “Voice of Authority” “to make fun of old blowhards, misled leaders, captains, presidents, and experts.” For more, see Lily Scherlis, “I Am Talking to the Part of You that Does Not Speak,” November 8, 2021, https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2021/11/laurie-anderson-delivers-2021-norton-lectures.

63White, "Great Expectations.”

64The Kitchen, invitation card for Benefit in Celebration of the Premiere Screening of Two Moon July, July 10, 1986, The Kitchen Archives, TKC20. Bowes stated that this range of interdisciplinarity was the inspiration for the work’s title: he thought of the reference to “two moons” as an appropriate evocation of what he called the “multiplicity” that defined The Kitchen as a place where a range of disciplines and practices existed alongside one another. The title also refers to the rare occurrence when there are two full moons in one month, which occurred in the month in which the crew shot Two Moon July, in July 1985. Bowes, interview.

65 Thomas Crow, quoted in “The Look of the Medium,” Revolution of the Eye: Modern Art and the Birth of American Television – Online Exhibition, organized by the Center for Art, Design, and Visual Culture, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and curated and designed by Dr. Maurice Berger, https://revolutionoftheeye.umbc.edu/introduction-the-look-of-the-medium/. For more on how exchanges between art and popular culture shaped television primarily between the 1950s and 1960s, see Spigel, TV by Design.

66 My use of the term “metacritique” draws from Judith Barry’s argument: “In the absence of a clearly defined oppositional sphere, attempts to focus on the artwork’s ability to question, to contest, or to denaturalize the very terms in which it is produced, received, and circulated must be located in the work’s ability to contain within its boundaries the possibility of its own metacritique.” Barry, “This Is Not A Paradox,” 251. The Kitchen references its role in laying the groundwork for television culture in a letter: “By juxtaposing live performance with innovative video works, TMJ captures the special energy that characterizes The Kitchen as a forerunner of contemporary culture.” The Kitchen Center for Video, Music, Dance, Performance and Film, proposal for “The Kitchen Presents—Two Moon July,” submitted to JVC Company of America, September 30, 1986.

67 Another articulation of the double nature of Two Moon July appears in then-Executive Director Barbara Tsumagari’s program note for the benefit screening: “Director Tom Bowes has gathered a collection of works by over twenty artists in an impressionistic portrait of the ‘idea’ of The Kitchen.” Barbara Tsumagari, program note in program for Premiere Benefit Screening of Two Moon July at The Kitchen, July 10, 1986, The Kitchen Archives, TKC20. By referring to the work as a “portrait of an ‘idea’ of The Kitchen,” Tsumagari alludes to the idea as a double in the same way I describe the broadcasted image as one.