Photo: Nick Walkley

Photo: Nick Walkley

Photo: Nick Walkley

“Is this the original??!”... I ask in amazement, before answering my own question: “No... of course not.”

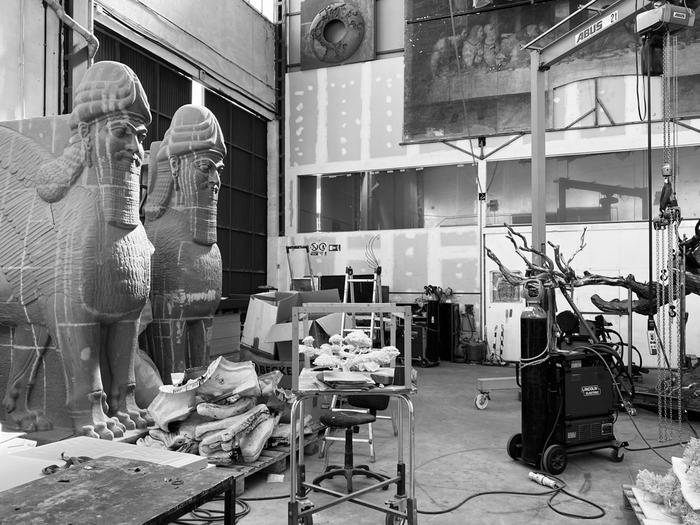

I know it, but I am suspended momentarily in a state of false belief. The original Raphael Cartoon The Sacrifice at Lystra is in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. I am in Madrid, receiving a guided tour around the studios of Factum Foundation, an organisation renowned for their production of facsimiles – copies or reproductions of cultural heritage objects. I am surprised by my own reaction, utterly convinced by the Raphael facsimile’s surface detail, its worn appearance, enough to momentarily think that this was an original. The way the canvas is stretched around the frame looks authentic, as does the surface and texture of the painting. Yet here it hangs, not in a pristine climate-controlled gallery environment, but a workshop, half draped in plastic whilst the midday heat blazes down outside in the industrial district east of the city. Sunlight beams through the skylights of the old factory roof, illuminating the dusty concrete floor. The grinding sounds of power tools echo from an adjacent studio, where a pair of Assyrian lamassu guard the entrance to the workshop. Surrounding me, standing against the walls, are panels from the tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Seti I. His sarcophagus lies centrally on a wooden pallet, complete with its inscriptions and worn stone edges. Behind it, the Sepulchre of Cardenal Tavera is stacked upon the Sarcophagus of Tutankhamun, across from the watchful eye of a Bakor monolith.1 Elsewhere, a backdrop provided by Rembrandt reflects in a huge silver plate engraved with the map by 12th-century Islamic cartographer al-Idrisi.2 I am bewildered as my tour guide moves effortlessly between explanations of African rock art and the Italian Renaissance, from stories of Egyptian pharaohs to the Xingu people of Brazil. I remind myself that not one bit of what we are looking at is ‘real’, ‘original’, or ‘authentic’. Yet, the stories these objects are able to tell are absolutely real.

This essay takes the form of a short story, recalling the author’s explorative encounters during a two-month research residency at Factum Foundation taking place in the spring of 2022. Through its three-part structure, this auto-ethnographical account reflects on the author’s experience of seeing deeper into the surface of the facsimiles, deeper into their complex layering and the multi-sensorial perception of the matter they are composed of, and into the synergy between hand craft and machine power which plays out in their production.

1 I later learn that these shells are artefacts of production, the positives from which moulds were taken to produce the sarcophagi facsimiles. But in this initial superficial encounter, they are merely images representing the original objects.

2 For a full oversight of Factum Foundation projects, see https://www.factumfoundation.org/allprojects.

Factum’s expanding assemblage of reproduced objects - Photo: Nick Walkley

My guide escorts me away from the random assemblage of Bakor monoliths and sarcophagi, past the central stair and through a door into the printing room. Here I see an enormous flatbed inkjet printer, which is rapidly reproducing a relatively small image of The Extraction of the Stone of Madness by Hieronymus Bosch. Seeing it here under production, there is no doubt in my mind this time that it is not a 15th-century painting. Besides, by chance I had seen the original only a few days earlier on display at the Museo del Prado, one of my first stops on arriving in Madrid. The printed Bosch is the correct proportion and colour, but it has a curious flatness despite the texture of the white surface it is being printed upon. Whilst the colours appear from the print head gliding back and forth, my guide explains the process of recording these paintings. She describes how the colour is captured using composite photography, where a single high-resolution image is produced from many individual photographs. She tells me how the surface texture is also recorded using Factum’s very own invention, the Lucida 3D Scanner, which maps the surface with an accuracy of up to 100μm through recording the distortions in a beam of laser light as it moves across the object.3 To rematerialise the painting, first the surface texture is reproduced through the process of Elevated Printing, an enormous flatbed printer which cures layers of ink by UV light as it prints, each between 8 and 10μm, stacking them on top of one another.4 It produces a hard, rigid surface, which is then used to create a silicon mould as a reusable and easily removable negative image. The final surface is then cast from this in white gesso. It bears the impression of the canvas void of colour, revealing only its surface texture. My guide shows me another one heading into the printer, and as we attempt to guess the artist it is almost a disappointment to later have their identity revealed, whilst we had been appreciating the beauty of the texture alone.

Factum’s definition of a facsimile is one that produces objects of visual parity, my guide goes on to explain: “Here we create copies so accurate that the naked eye cannot tell them apart from the original.”5 This comment causes me to stop and think and to enquire more. Is this really where Factum draws the line, at creating a visual copy only, ignoring all other sensorial experiences?

3 The Lucida 3D scanner was conceived and developed by artist and engineer Manuel Franquelo together with a team of artists, conservators, and engineers at Factum Arte. For full descriptions of the recording technologies used by Factum, see https://www.factumfoundation.org/ind_fa/36/recording (accessed 28 Nov 2022).

4 The Elevated Printing process has been developed and enhanced in collaboration with Canon Production Printing. For further detail, see https://www.factumfoundation.org/pag_fa/1728/elevated-printing (accessed 12 Dec 2022).

5 The guide in this story is based on a series of initial introductory tours and incorporates additional sources from other ‘guiding’ conversations and documents, in this example quoted from Factum Foundation, ‘Factum Foundation Volume III 2016 - 2019’, 2022. 11.

A flatbed inkjet printer begins to apply colour to a gesso texture - Photo: Nick Walkley

Meanwhile, a busy-looking employee rushes in to collect the freshly printed Bosch image. In the other hand she carries a mixing bowl, and her dark grey overalls are dashed with white daubs. “This is Silvia,” my guide says. “She is extremely busy today. Her job is the final stage in this process – she adds the finishing touch to the surfaces of nearly all of Factum Foundation’s projects by hand. She has a lot to do, so we won’t bother her for now.” Silvia remains focused on her task as she passes us without a word. Immediately I am curious. I had understood that Factum were pioneers in digital reproduction methods. “Did I just hear you correctly?” I ask. “…that the facsimiles are finished by hand?” “Many of them, yes…” she replies matter-of-factly as she escorts me from the printing room, back into the main workshop, and up the short open riser steel staircase, the sound of our steps resonating through the old factory hall. We ascend through its half landing and 90-degree turn, reaching the top and pass Silvia again in her studio, surrounded by paintbrushes and endless pots and jars.

I am led to turn and climb another staircase where I am introduced to the digital artists, photographers, architects, engineers, and members of the communication team working across two stories of office spaces. On the computer screens, I see sculptures, architectural details, building interiors – sculptural objects which have been digitally recorded.6 The screens show surface meshes in virtual space. The camera goes no deeper and sees nothing more – behind these surfaces there is only a void. Whilst these models are somewhat superficial, they are not flat.7 The pixels display detailed textures, which once zoomed in become rolling landscapes. They show the surfaces’ form in incredible detail, but nothing beyond it. I am puzzled – surely the reproduction of such a surface requires knowledge of the forces and material which first shaped it?

As my tour concludes, I reflect back on it. I had read much about Factum prior to this introduction, so I am surprised at myself for even momentarily believing the Raphael to be authentic. I am astonished too by the individual expertise and its range across both digital and traditional media. I recall my guide highlighting Factum’s own particular definition of a facsimile as a visual copy, rather than an exact one.8 Can this be correct that it is only an object’s visual appearance forming its facsimile? Is the visual illusion of authenticity merely a superficial deception, or is there something more to be learned from looking more deeply at the complex composition of these reconstructed surfaces?

6 Factum’s recording techniques for sculptural objects and interiors include photogrammetry, structured light scanning, and LiDAR scanning. See https://www.factumfoundation.org/ind_fa/36/recording for technical descriptions (accessed 29 Nov 2022).

7 As Sybille Krämer observes in this volume of Metode, the idea of a 2D surface is an entirely human invention. Flatness is an artificial creation in a world of ‘illustrated and inscribed surfaces’, yet paradoxically, as she writes, “We are socialized in the tradition of well-known rhetoric: fertile thinking is oriented toward depth, and profoundness is desired, but superficiality is devalued; being directed to the surface is nearly taboo.” Conversely, reducing paintings to the reproduction of their 2D image seems to have become an accepted normality, a falsity that a close examination of their surfaces reveals instead as a rich topography.

8 From the definition of a facsimile as “an exact copy, especially of written or printed material” – Oxford Dictionaries, s.v. “facsimile (n.),” accessed 10 June 2022, https://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/facsimile.

It is a Saturday, around two weeks after my arrival. After a morning of sightseeing in Madrid, I find a vacant café table looking out across the Plaza Mayor and order a glass of Rioja. I take shelter under an umbrella from the intense afternoon sun where I am able to admire the frescoed ornamentation adorning the Casa de la Panadería. Pausing with this view across the square, my thoughts return to some of the theoretical study I undertook before arriving in Madrid.

I recall John Ruskin, and his writings on restoration – “What copying can there be of surfaces that have been worn half an inch down?” he once wrote. I wonder what he would make of the work that is being done at Factum. It is almost as if he had foreseen the copying of objects when he wrote, “The whole finish of the work was in the half inch that is gone; if you attempt to restore that finish, you do it conjecturally; if you copy what is left granting fidelity to be possible (and what care, or watchfulness, or cost can secure it), how is the new work better than the old?”9 It is a line from 1849 in which he seems to foresee Factum’s work. Here in Madrid, worn surfaces are being copied, quite convincingly. Fidelity, it seems, is possible – at least at a surface level.

Richard Sennett observes of Ruskin that “his prose at its best has an almost hypnotic tactile power, making the reader feel the damp moss on an old stone or see the dust in sunlit trees”.10 Ruskin was also a master of reproduction, though through a multi-sensorial description inside the reader’s imagination. We see, smell, hear, feel, and even taste the many objects he describes in his writings, through the power of his carefully crafted words and their hypnotisation of our imagination.11 Ruskin was consciously aware of the limits of the technology of graphic reproduction in his time, using these vivid descriptions in words as a means of negating for the loss within the ‘practical illustrations’ he was able to supply his readers. For The Seven Lamps of Architecture, Ruskin had produced the plates himself: “its etchings were not only, every line of them, by my own hand, but bitten also, (the last of them in my washhand basin at ‘La Cloche’ of Dijon,) by myself, with savage carelessness”.12 He is ‘scornful’ of the techniques needed to reproduce the images in mass quantities, or of anything not that of ‘steady hand and true line’, and trusted seemingly few engravers to reproduce the plates in the way he wished. As Suzanne Fagence Cooper has also observed, it was through observational drawing that Ruskin’s deep understanding was formed and that his continuing relevance today is in showing us how ‘to see clearly’.13 I sense a similar level of detailed observation at Factum, but how much of that are they truly able to reproduce? How much remains in our imagination? How much is lost?

I finish up my glass of wine and head north from Plaza Major. Traversing the city in the afternoon heat, I come across a 19th-century water tank. To my delight I discover it has been converted into a gallery, the Sala Canal de Isabel II, which is showing an exhibition called Matter by photographer Aleix Plademunt. A number of themes centring around materiality run through the Malrauxesque assemblage of black-and-white images displayed around the walls inside this cavernous, hollow brick structure. It starts with an enormous screen displaying interference from a cathode-ray tube television. I curiously consult the guidebook, which informs me that 1% of this is displaying cosmic background radiation from the Big Bang. The exhibition continues with images of objects, minerals, sculptures, the sun, buildings, trees, the sea, human placentas, landscapes, machines… the theme running through them being the ‘matter’ they are made of. The guidebook explains: “Derived from mater, the Latin word for mother, matter refers to the substance from which all things are made. In English, the word matter can also indicate importance or significance – something to be concerned about.”14 Through the short explanations of each image, we are engaged to think about the material of the objects, together with the issues surrounding the stuff from which they are made. Not least, to look closer and deeper at an object, through this assemblage of photographs of things, to see them for what they are made of.

9 John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, 2nd Brantwood Edition, 1892. 354. This passage comes from a discussion on restoration with which it is assumed here that reproduction is an overlapping field through use of the word copy.

10 Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008). 106-118.

11 Despite the vast devastation caused by two world wars in the area since it was written, this author has been able to trace Ruskin’s evocative description of approaching and entering Amiens Cathedral from the train station, complete with ham sandwich. The guide remains useful and insightful, and the experience of visiting the cathedral matched the expectation created by the text. For images of my visit with quotation, see https://www.instagram.com/stories/highlights/17989928689621739/, and John Ruskin, Our Fathers Have Told Us, vol. Part I. The Bible of Amiens, Chapters I. ‘By the rivers of waters’ and IV. Interpretations, 2008, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/24428.

12 From the ‘Preface to the edition of 1880’, John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture (New York: Dover Publications, 1989). v-vii.

13 Suzanne Fagence Cooper, To See Clearly. Why Ruskin Matters (London: Quercus, 2019).

14 My italics; Aleix Plademunt, ‘Matter’ (Exhibition Guide, Sala Canal de Isabel II, Madrid, 12 May to 24 July 2022).

Gate of All Nations, Persepolis, Iran, and a ‘replica’ of the Lamassu from the British Museum at Factum Foundation in 2017 - Photo: Aleix Plademunt

One of the themes or matters running through the exhibition is the displacement of cultural objects. Images of carved stones appear regularly: Egyptian obelisks, classical statues, and lamassu – Assyrian deities, part lion, part human, part bird, often in pairs. One is pictured at the Louvre; another shows a ruined pair in Iran. Another is standing in a factory, which I recognise instantly as Factum Foundation’s workshop. I know the steel stair, the same one I have been walking up and down daily. Plademunt had photographed a cast waiting for shipment to the Netherlands, describing it as a ‘reunified replica’.15 Another image shows the prototype positives milled in high density polyurethane used to create the moulds, which still welcome me every morning to the workshop. For the casual viewer, is it any matter whether they are cast, milled, or carved? They all take the form of lamassu, their surfaces communicating a symbolic message. Is it necessarily important which particle matter is combining to form them? Certainly, the carved stone connects it with the original time and place – the very particles carved by the first artist.16 But for the Assyrian artists, the stone provided merely the material matter of a substrate, giving form to their fantasy. Does it matter that something as un-Assyrian as high-density polyurethane foam might continue the trajectory of these objects in their original size and form? Which matter is the more important, the message or the material? Do they not all carry the same symbolic image of lamassu?17

15 The lamassu were rematerialised from the 2004 recording in 2014 and 2017. For a full project description, see https://www.factumfoundation.org/pag/1079/ (accessed 29 Nov 2022); a video of the donation of the lamassu to the University of Mosul can be viewed at https://vimeo.com/374813888 (accessed 12 December 2022).

16 The idea of ‘time and place’ is an indication of originality according to Walter Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility (Third Version)’, in Selected Writings Vol. 4: 1938-1940, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, 1st pbk. ed (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press, 2006), 251–83.

17 An idea explored in depth in this essay: Bruno Latour and Adam Lowe, ‘The Migration of the Aura, or How to Explore the Original through Its Facsimiles’, in Switching Codes: Thinking through Digital Technology in the Humanities and the Arts, ed. Thomas Bartscherer and Roderick Coover (Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 275–98.

The lamassu at Factum’s workshop entrance in 2022 - Photo: Nick Walkley

Silvia’s studio - Photo: Nick Walkley

I wait at the top of the steel stair outside Silvia’s studio. Outside, the same Bosch painting I had seen a week earlier is now presented at the entrance on a stand awaiting approval. I take the opportunity to admire it. Its varnished surface glistens in the natural light, and the yellowish text I had seen emerging from the printer is now gleaming with gold. Silvia makes her way up the stair from the studio floor, and we begin the meeting I had managed to squeeze into her busy schedule.

We begin by discussing the paintings. As I had observed – Factum’s facsimiles of paintings are especially convincing, and something transformative appears to happen to them before they leave this studio. Silvia shows me a test print of the Bosch painting, taken directly from the printer. She says:

Machines cannot recreate the whole aspect of the object because … working with the materials, working with the pigment, working with the varnish, how you apply the varnish – how you work with the materials, changes the object. I give another language, another layer of language.18

18 Interview with Silvia Álvarez, 22 June 2022, Madrid.

Silvia with the trial print of Bosch’s The Extraction of the Stone of Madness. Photo: Nick Walkley

Silvia’s intimate understanding of materials and their behaviours are channelled into this retouching process, one she has learned through her career as a conservator. The paintings displayed in galleries that she previously worked with have each gone through a series of formational and restorational processes contributing to their complex, layered surfaces, the composition of which Silvia has learned to read and interact with. In her role at Factum, Silvia is now applying that experience to recreate those surfaces with the inclusion of printed matter:

You can imitate the colour, you can create the colour of, for example, the red, but the pigment has something completely different from the red that the printer can produce. If you start to play with the materials, that helps you to increase that capacity that the printer has to create, then you get the same feeling. They all have different languages than the printer, but if you combine both, maybe you can have the language of an oil painting.19

Silvia understands deeply how layers of pigments and varnishes combine and how we perceive them. Whilst the scanning and printing processes are checked to ensure colour accuracy throughout, they do not capture or reproduce the object’s materiality – our experience of the material.20 There are also some materials, such as gold, that the machine cannot print. I watch later as Silvia works at close proximity with a painting, her nose almost touching the canvas as she closely eyes and adjusts every mark on the printed gesso.

It is not just Silvia’s touch that seems to make this final transformation, but a process of touching that verifies its completeness. “I am always touching things,” she tells me. “I spend the day touching things. Someone, a supplier, brings me materials, I start to touch them.” I watch as she touches the copies as she explains. I recall the Prado Museum attendant’s panic as they caught visitors violating their ‘no photography’ policy and wondered what their reaction would be if I started touching the paintings there. For Silvia, it is an important part of the process. At some point she has acquired the knowledge of how a centuries-old oil painting feels to the hand, a privilege most of us are not granted. “It’s more to get how it looks, how your eyes interpret the surface. For example, when I touch this painting right now, I think, no, it’s not the original, it’s a little bit dry. … But at the end, the important thing is [for it] to look like the original, to have the feeling.”21

19 Ibid.

20 Using a definition of ‘materiality’ understood simply as ‘the thinginess of things’, from Tim Ingold, ‘Materials against Materiality’, Archaeological Dialogues 14, no. 1 (June 2007): 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203807002127.

21 Ibid.

Silvia with the finished facsimile of Bosch’s The Extraction of the Stone of Madness. Photo: Nick Walkley

Some days later, I meet with Adam Lowe, the director and founder of Factum Foundation. I question him on my observations of Silvia’s transformative touch giving a kind of ‘vitality’ to the printed images. He answers defiantly.

Silvia’s job is only in the retouching, so she’s not painting the pictures. She’s only concealing artifacts of the process. […] Silvia’s not adding anything to the experience. It’s not an artisanal thing to say, ‘it’s her touch that makes you believe it’s not printed’. In an ideal facsimile, Silvia would never touch the surface at all – all she would be doing is fixing the surface onto a canvas and stretching that. So, it’s absolutely wrong to think that it’s human touch that is the thing that people are seeing.

Accepting that it wasn’t touch I had seen in the finished facsimiles, but that I was seeing much touching in the workshops around me, I protest with some conviction remaining in my observation of ‘handwork’ that there was also an aspect of artisanal craft within this mechanical reproduction process.22 “Yes,” I reply, “but I find it fascinating with this process, with the technology, that you still need a pair of hands in the end, to finish the facsimiles, to make them believable.”

“Well, there’s things technology does and things that hands do,” Adam concedes. “But I think that you are a bit transfixed on a romantic notion that I don’t think is correct. So, it’s not Silvia’s touch that makes Factum’s facsimiles real, okay? At all. That’s not correct.”23 I sense a slight irritation and move to another line of enquiry.

At the bottom of the stairs from Silvia’s studio lies the facsimile of Seti I’s sarcophagus. I stretch out my hand to feel the sarcophagus’ surface with my fingers. Despite the appearance of stone, there is not as great a difference in temperature as I would expect, and it is slightly waxy. I knock on it and listen. It echoes with a dull thock, and not a dink, as I imagine the alabaster of the original might have done. The sunlight beaming down from above reflects straight back from this opaque beige surface, unlike the alabaster samples opposite which have a slight ethereal hint of whiteish-yellowish translucency where the light permeates the surface. The alabaster appears to glow from within.24 In form and dimension the sarcophagus appears to be a faithful copy – it is a remarkable reproduction of a full-size three-dimensional object. But through the experience of its materiality, the illusion is revealed.

I questioned Adam on this, and he explained:

Our goal was to make a facsimile of the sarcophagus that’s in Sir John Soane’s Museum now. But if I had got a new block of alabaster, it would have totally different featuring and totally different veining, so it wouldn’t be a facsimile. It would be a reinterpretation of something.25

The sarcophagus provided a difficult dilemma. Here the uniqueness of that particular stone provides part of the object’s visual identity. A new block of stone would alter that visual state, though that was an option that was considered:

We did run a lot of tests early on in alabaster before I decided to do it with Océ [elevated printing], but the decision was that doing it in alabaster is a perversion.26

I come to understand that the original sarcophagus’ visual appearance was a unique construct of the object’s journey through time since it was created. Adam explained further: “It entered London as a white alabaster with blue infill. And now it’s a honey-coloured alabaster with white veins with no infill. And that’s something that happened as a result of cleaning, and over time. […] If I was going to want to make a recreation of the way the sarcophagus looked in 1821, when it arrived in London, that would be a different operation, and I might decide to make that in alabaster.”

I begin to understand the problem. Another block of alabaster would create an entirely different version of the object and would be a copy with an entirely different purpose than the one I see in front of me. Decisions and compromises had to be made within the limits of the technology and according to the purpose of this facsimile – to convey the object’s form and colour.

Looking from as close a close proximity as the naked eye would allow, I eventually see how the outer shell of the facsimile subtly reveals its construction. I detect the joints of the panels, which Silvia had once painstakingly concealed using an acrylic putty blended with watercolour. I begin to see that it is dots of ink, not stone particles, which make up the surface. Like viewing a Georges Seurat painting, taking two steps back from viewing the image at close range reveals once again the subject rather than the technique. Furthermore, to Silvia’s annoyance, the facsimile’s exposure to sunlight over time has exposed faint traces of brushstrokes with the different rates of deterioration for paint and print. Her discreet disguising by extending the veining of the ‘alabaster’ between the joints of the printed panels is now slightly more visible than it was. Just like the original, this version is also now changing with the light and has its own new trajectory.

22 Having approached this from a Norwegian perspective, where håndverk is the literal Norwegian translation of ‘craft’, similar to the German Handwerk.

23 Interview with Adam Lowe, 8 July 2022, Madrid.

24 Photographs from Factum’s own recording also show this quality in the original sarcophagus: https://www.factumfoundation.org/pag/1315/seti-s-sarcophagus-recording-and-facsimile (accessed 30 Nov 2022).

25 Interview with Adam Lowe, 8 July 2022, Madrid.

26 Ibid.

Detail of the Seti sarcophagus facsimile at close proximity.

Detail of the Seti sarcophagus facsimile at a normal viewing distance.

Silvia and her colleagues concealing the joins of the facsimile.

Adam told me how his work with Factum grew out of his interest in print making and digital printing, which has since progressed into the reproduction of three-dimensional surface. At this point, I began to see the objects around the workshop as images which have escaped from the pages of a book – prints rebelling against flatness, finally able to show their three-dimensional form. With it, my perception of the objects also changed. As with the printed images in a book, they exist to illustrate an object within a wider context. Within the history of printing, images have been reproduced with the technological means available, be it woodcut, copperplate etching, or chromolithography, each with a varying degree of loss of information or necessary subjective intervention as part of the process. The printing process at Factum then follows that pattern. The technological processes allow for accurate, detailed reproductions, which in three-dimensional form receive the label of ‘facsimile’. Adam explains:

The facsimile is trying to achieve an objective proximity to the object that it was derived from, so that the ability to identify and react to the other material evidence of the surface – whether that’s a colour mixed with a surface or whether that’s the surface of an alabaster or something else, gives you an ability to read that object.27

I learn that Silvia’s interventions are a necessary part of that process, in striving for accuracy. Total objectivity is an unachievable target, which Adam acknowledges:

Of course, there are subjective decisions, but they’re subtle. And the subjective decisions are not the subject: The subject is proximity. The subject is correspondence. The subject is making the facsimile have the qualities of the original, or appear to have the qualities of the original.28

Silvia too knows her role in the process should be a mechanistic one, but she is a little sceptical of Adam’s ideology of the perfect facsimile delivered entirely from the machine:

He calls me Cyborg sometimes, like a robot! Sometimes he likes the idea of a combination of handmade and machines, and at other times I think he loves to have the machines make everything, I don’t know. The technology can probably change everything, but the things that humans made I think a human has to make.29

Silvia evidently believes in the human experience of seeing, making, and creating. From a conservator’s perspective, her position differs from Adam’s, an artist who places his faith in the objectivity of machines for the accurate reproduction of art. Despite this slight tension, they agree on the purpose of the objects they are creating. Silvia had also told me:

It’s not just only to recreate the visual aspect, it’s to recreate the whole object and also to document the history of that object. Because the idea of Factum is not only to create a facsimile, it’s also to keep the information of that object. I make the possibility that people can consult that information.30

They are not intended as fakes, but facsimiles.31 What is the difference, if any? A fake might aim to deceive us into believing it is an original. But as I experienced, a facsimile can also do the same. Is then the only difference that we are told that a facsimile is a reproduction? In their manipulation of material matter, Adam, Silvia, and the rest of Factum’s production team create the illusion that we are looking at an original object. A master forger may be said to be doing the same. However, Factum’s objects are not made to deceive an observer but to convey information to them, and Factum’s struggle in doing so is in confronting the prejudices against non-authenticity. Their facsimiles are made through careful observation, reproducing its surface with the honest intention of telling us how an object is and to allow us to see it in a place it is not or cannot be.

Here I recognise Ruskin’s clear observation and his ability to describe and reproduce. “If Ruskin was around now, he’d be in Factum!” Adam declared confidently. “Ruskin’s obsession is things should be allowed to be what they are, and in them being what they are, you read not only them, but also their trajectory.”32 This could be said both of Ruskin’s etching of the weeds growing amongst the carved crockets of St. Lô, and of Factum’s Seti I sarcophagus facsimile, showing its discolouration and worn edges. As we talk, Adam recites further references from the pages of Modern Painters or The Stones of Venice. Ruskin is among many thinkers who he can draw upon from memory, traceable amongst the many influences forming his vision for Factum’s work.

One afternoon, a group of guests arrived for whom a tour of Factum’s premises had been arranged. The delegation of museum curators and art historians were as astonished as I was on first viewing the random collection of familiar objects assembled in this dusty factory. I was especially eager to see their reaction to the Raphael Cartoon facsimile. Adam stood before it and explained the process of its reproduction, as well as the new conclusions being reached through the study of the cartoon’s surfaces.33 The surface textures revealing the pouncing marks can be isolated from the colour in the online viewer, revealing the way in which the images were transferred to derivative cartoons before being transferred to tapestry. The original cartoons are then themselves a surviving artefact of a reproduction process. Whilst there was some initial suspicion amongst the group towards the idea of a copy, it was quickly appreciated that in this copy, there exists a close study of the surfaces and an intense interaction with them which had the potential to reveal something previously unseen. In that moment, in truly seeing the surfaces of facsimiles, scepticism had turned to unanimous approval.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Interview with Silvia Álvarez, 22 June 2022, Madrid.

30 Interview with Silvia Álvarez, 22 June 2022, Madrid.

31 ‘Fakes’ was a term used by Daniel Zalewski, ‘The Factory of Fakes’, The New Yorker, 28 November 2016.

32 Interview with Adam Lowe, 8 July 2022, Madrid.

33 See https://www.factumfoundation.org/pag/1560/the-high-resolution-recording-of-the-raphael-cartoons for the full project description (accessed 29 Nov 2022).

Adam Lowe presents his facsimile of Raphael’s The Sacrifice at Lystra – Photo: Nick Walkley

On reflection of my journey described in this essay, I have learned to look closer, to see beyond the illusion. As a sort of ethnographer, immersing myself in this community over a prolonged time, I have become the illusionist’s apprentice. Having learned the magic trick, I saw beyond the magic. Instead, I gained an appreciation for the craft, a balanced combination of high technology and human skill. Silvia’s finishing contribution is representative of many who work between this combination, work which plays out upon the surfaces, and deep within them. These surfaces have multi-layered depth, like a palimpsest, as Tim Ingold’s contribution to this ‘Metode’ volume explores, with the notion of surfaces having a permeability. But is our perception of that depth or permeability not dependant on the matter which makes up that surface, and also the scale at which it is experienced? Soil has a much different materiality (or ‘soiliness’) than alabaster, and different again for us than a tree or a micro-organism. As the example of the alabaster sarcophagus has shown, reproducing such permeable surfaces can prove to be a complex task, especially where a surface has had a unique story written into it by its spatial-temporal journey. As Sybille Krämer also writes in this volume, going beyond surface flatness and superficiality is necessary for a deeper understanding of what we are truly seeing. The illusion then, is perhaps that there even is an illusion. The subject is actually ‘matter’, and how looking more closely at that matter can lead to a clearer reading of what is seen on the surface.

“Investigating a surface through the lenses of facsimiles opens up a string of thought about practice that not only create perfected copies of culturally significant surfaces, but the exploration of surface’s depth is literally in the core of such a practice. In fact, creating facsimiles reveals the complexity of surface production - inscriptions of time and human/non-human actions on surfaces subjected to the study require not only cutting edge technology, but as Nick precisely describes - the depth of the surface can be copied only by human hand that makes is believable and unrecognizable to the original. The limits of technology in surface making is clearly set to the Interface between non-human (the machine) and the dexterity of hand (human) that is positioned not only as craft, but as an intrinsic part of the practice.”

“The essay’s unique perspective of critical writing builds up arguments through interviews and personal observation intertwined with theories and practice that all together provoke curiosity and in depth thinking about surfaces.”

“Nick’s essay is interesting from the point of view of the issue of the productivity and mode of production of surfaces: On the one hand, producing a specific texture of artefacts’ surfaces is what contributes to their feel of authenticity (not just the color applied to them and the accuracy of colors). On the other hand, there is a really interesting account of how professionals at Factum Foundation produce surfaces – mechanically and through human touch.”

“Is it at all possible to acquire total objectivity in a generative process? Does the removal of the human in favor of mechanical reproduction equate objectivity?”

“Reading it, it was like I was there, in Madrid, in the Factum Foundation. ”

“I like your article, I find your way of narrating your experience in Factum interesting, and you perfectly portray our points of view, mine and Adam's. Perhaps my opinion about the fact that the manual work of my colleagues and myself is so important is due to the fact that I consider it essential that Western societies preserve artisan traditions and coming from a country like Spain where artisan trades are not valued makes me be more veligerous towards the idea that a machine can do everything.”

“I consider that it has nothing to do with your article on Facsimile, but at the end of the reading I asked myself a few things. Is it more important to keep the object itself? Or, on the other hand, is preserving the knowledge of the techniques of how the objects were made and keeping artisans within society who know how to execute these objects the true achievement? Or a third option, is it to find a balance between both aspects so that knowledge really flows?.I think you know which one I prefer. What do you think?”

- Reflections from Silvia at Factum Foundation after reading the essay

Nick Walkley, “The Matter of Illusion,” Metode (2023), vol. 1 ‘Deep Surface’