Photo: Åsne K Mellem.

Photo: Åsne K Mellem.

Hei Solveig :)

Disse hovertekst-feltene kan vises ved å linke til #hovertekst-1 (for denne boksen) og #hovertekst-2 for neste boks osv. Du kan legge til flere ved å trykke på knappen som dukker opp når du hovrer over bunnen av denne boksen — “Legg til rad”

Her er det en boks til. Den vises når du lager en link i en av de andre blokkene som refererer til #hovertekst-2

I do not know why I needed to start to write in my mother tongue. I have not done it in a long time, other than when I communicate with my sister, parents, and friends in Finland. I mainly practice my thinking in English, but today I needed to translate Åsne’s text from Norwegian to Finnish. Something happened. I do not know much about the history of Kvens, which makes me feel ashamed. I can read Kven, and thus I understand it. Still, our connections are unclear to me, but not necessarily distant.

We educate the younger generation to launch a wooden boat into the ocean, make them feel how the waves rock the boat, how it feels to lead the oars through the water surface, and getting friendly with both the boat and the ocean, to move in certain directions. Through the feeling of hard wood rubbing your palms, the taste of salt on your lips, maybe facing the fear or excitement of being there alone on the ocean with each other and the landscape, and for the lucky ones, pulling a fish over the gunwale on the boat, being forced to hold on to the slippery skin with firm hands, removing the hook and daring to cut the throat, all done while the boat is in motion. This is where we argue that a space exists for possibilities to reconnect again, to the local, to Kven, to make acquaintance, and become-with the landscape, and become aware of others that belong to it. Maybe this also contributes to developing a care for the place and its stories?

Wool! Fiber!

Maybe we need to examine the fish?

A material you can relate to, regardless of whether you’re invested in käsityö [handicrafts] or not. You always go back to it, even if plastic is taking over. We even have an intimate relationship with it, with wool underwear being the closest layer, right against your skin.

The fish and the sheep have a lot to do with each other, even if the wool in yarn production was gradually phased out by hemp over time. Nevertheless, wool and sheep were crucial for the Lofoten fishery.

The boat rugs are fascinating. This connection between warm and caring handicrafts and the fisherman, where individual rugs were produced for use at sea. The sheep fleece was not as easy to scrub and wash free of fish residue, so the woven and knotted rugs were more practical. The fisherman’s initials were often embroidered on the rugs, often surrounded by a embroidered heart. They are not necessarily linked to the Kven culture (yet). But that doesn’t matter; they must have been, all those who went out to fish in Lofoten. The men who carried the boats over from Lyngseidet to Kjosen to avoid the heavy sea conditions on the tip of the Lyngen Peninsula. The wives who knitted and wove. The fisher mittens, the so-called totomling, with a double thumb, so that you could turn it around if it wore out. When they returned, not only the nets had to be mended, but also the rugs and clothes. Wool becomes heavy when it gets wet, but generates warmth as it dries. And if you keep the lanolin in the wool, the natural fat layer of wool, it becomes waterproof.

Today’s handicrafts and wool are often associated with plant-based dyeing, with colors that are pretty, delicate, and beautiful. But what about the gray? The “boring” shades that today can’t compete with the chemical dyes produced in large-scale manufacturing?

And then you have the fishing nets. Wool yarn is recorded as a used material, but it was quickly replaced by plant fibers when it came through trade. First hemp, then cotton. Today, plastic. (This is what I’m working on now at Refa: https://www.facebook.com/reel/205463492075051). I took the job to get a realistic impression of today’s fishing industry, while also working my way in from a historical perspective. There is nothing glorified about Refa; it’s raw and simple. Today, it takes about 30 minutes to assemble a fishing net. Quick and easy. But they were manually assembled not that long ago, and therefore also cared for in a completely different way. Repairing nets is now taught as a last resort if you get a tear in the net out at sea. But historically, this was a whole seasonal job, where they maintained the cotton nets that got damaged during the fishing season. Just think of how many old nets hang around in boathouses, so well-preserved, not used for years.

The fishing industry in a handicraft context is very interesting. People often talk about handicrafts, farming, and fishing as three separate elements, but the reality is that they are historically closely connected. Handicrafts were crucial for the fishery, and fishermen engaged in handicrafts. Techniques and knowledge that we today associate with craftsmanship or textiles were essential knowledge on the fishing boats: mending, knotting, managing large quantities of nets. Scraping and oiling of wood, tar treatment, pounding, and mending.

But wool persists, despite Gore-Tex, plastic, and oil: it is closest to the skin, right next to it, and takes care of us.

And I write these thoughts while drinking coffee from a Moominmamma cup—a cup that I see differently now, after our discussions.

This essay is an experiment of knowledge production—a dialogue among three women that connected through wool and the practice of writing letters.

We are a group of three women: an artist, a researcher, and a museum professional, who at the same time struggle to be defined as “something”. Each of us has a different relationship to wool, yet, as we have come to see, wool dissolves the type of difference that would prevent us from finding our connection. For some of us, wool is a material to work with and create with—and more. For others of us, wool is a reminder of our need as academics to create a connection to tangible materiality, of the possibility that we have sat behind our computer screens long enough. How to read our text?

The string we spin takes us to the beginning, and further than the beginning. In the first part of our text, our voices merge in our exchange of letters that are raw—left to the reader as they were written, frequently with a cup of coffee. And not just any cup, but a Moomin cup—Nuuskamuikkunen, Moominmamma, Lille My. Sometimes the letters were written in our mother tongues, or the language we have learned to call our mother tongue, as other words seemed impossible to make use of. Hence, even as English works as our main language of communication, we write in different languages, too. Kven, Norwegian, Finnish, and Wool. These are our ways of telling a story about what it means to spin threads of knowledge. We have made our mother tongue available to you in our text, as you will see, but the translations will never fully grasp what was once said. This is the price of a compromise that we must pay. In the second part, we met at the same time and space. We sat around a kitchen table, drank coffee—but this time from old family porcelain cups—and wrote collectively. Later in the process, we included the comments, ideas, and thoughts of others to our composition, but did not subordinate them.

In this process, voices have merged, yet our voice within a rhizome, wherein “our” is also “mine”, has maintained its own voice-ness. This is the power of writing letters, and of writing as a feminine and feminist practice. Here, the femininity we refer to is not related to the association of working with wool, nor writing letters, nor is it a practice reserved exclusively for women. It is something much more complex than that. In France in the summer of 1976, Hélène Cixous wrote:

“It is impossible to define a feminine practice of writing, and this is an impossibility that will remain, for this practice can never be theorized, enclosed, coded—which doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist. But it will always surpass the discourse that regulates the phallocentric system; it does and will take place in areas other than those subordinated to philosophico-theoretical domination. It will be conceived of only by subjects who are breakers of automatisms, by peripheral figures that no authority can ever subjugate.”

(Cixous, 1976, p. 883)

Where do these threads now take us? Our composition has become a materialization of feminine practice of writing. As much as we spin threads, we unbundle. Do we any longer want to be identified as a researcher, an artist, and a museum professional? Is it enough for us to be women who write with wool?

Encounters in written letters, March-May 2024

At first, I thought of currents as breakers and waves. How different kinds of signals interfere, connect, or demand something. I was focused on water as an element and confused on how to get close and familiar with the concept. But when I chatted with Åsne, and when she talked about how she currently is engaged with raw wool, my attention shifted. And when she shared photos of the material she works with, I could almost smell the wool and feel the stickiness that animal fat leaves on fingertips. I am no longer stuck with associations constrained by water, although water, wool, and sheep go together in my head. Wool is everywhere, and still something that I take for granted.

And as Åsne explained, wool can be so many things as raw material. Wool, straight from the bag, where the skins are sheared off warm sheep bodies. The wool is straight from the sheep and not washed. As such, it can be sorted into different categories, after the quality and intended use. Wool is not wool.

Bundle of wool. Photo Åsne K. Mellem.

Currents—I resonate strongly with something of the same that Gyrid felt when writing about the centrality of the element of water. I resonate with Åsne and wonder what you look like. I want to meet you. Fish, sea, lake, river, sheep, tree, deadwood, drifting wood, thunder, past, history, grandmother’s house, cattle, barn. I think of power, the power of the sea as a non-human actor that moves in symbiosis with the moon, the gravitational pull that causes the tides—something that was so distant, growing up inland. I am a girl of lakes and rivers. The tide is foreign to me, but fascinating. Currents—it also brings me to this moment in time. Current—currency—how capital also intertwines with all of this, and how it makes everything seem superficial. How could we just talk about sheep, trees, the sea, the moon, and wool? Now, perhaps we can.

And wow, the tide. Tarja mentioned the tide. I have reflected upon it in a Kven context, but it is still happening. People moving from Finland to Northern Norway, experiencing the body of water moving, up and down, the tide. In contrast to the still waters of the inlands. I wonder how this has affected the language. Is there any difference in how the Kven language and the Finnish language refer to low and high tide? I don’t know. I have heard that the Kven language has different and more synonyms to words for “mountain” than the Finnish language, since the Finnish language did not meet the nuances of all the steep fjords and raw mountains that they met when coming to the North of Norway. A mountain in Northern Finland and in Yykeä/Lyngen in Northern Norway were two different elements of nature. I believe that the same goes for the word vaimo, much used in Kven as “lady”, or nainen, while in Finnish vaimo is a married woman, if I’m correct. But in the old days, you were a girl until you got married, and that stuck in the Kven language to this day. A lot got stuck in the gap between the cultures and language, as a lot is stuck in the gap between generations.

At the foot of the Lyngen Alps, seen from Moskivuono, Ullsfjord. Photo Åsne K. Mellem.

On different occasions in my work as a museum educator in Vesisaari/Vadsø, I have been working with raw wool, preparing materials for children to spin bundles of wool into threads. Once, I was preparing a workspace for children at an open day at the museum. It was outdoors, and while I was sitting on the lawn, struggling with the bundle-making, a group of elderly people commented on me fighting the wool. Instead of correcting me, they shared memories from the past, when their loved ones were preparing and spinning the wool. They remembered the sounds of the work, the smell, the touch, and even the humming from the people at work. I asked if they could help me or point me in the “right direction”. The answers they gave me surprised me because none of them knew. They remembered the activity, but they had never done it themselves.

… I had forgotten about our meeting outside the museum, but suddenly I remembered while reading. This was before I started experimenting with wool, but I had just been introduced to it through my professor, Hilde Hauan Johnsen. I didn’t know much about the material then, but I knew enough to engage in your frustration to “get it right”—I had recently felt this myself. I learned to spin over a patchy Zoom call with my professor, imposed by the Covid restrictions. I did not have my professor’s hands showing me the details and feel about such a fragile craft. I could not show her a thread properly, in person, asking her “is this right?”, whereupon she would take her glasses down from her head, place them on her nose, grab the thread, and say, “Hmmm, yes, this looks good” or “You should add more tension—here, let me show you!”

In some way, the Zoom call created an unexpected haze in learning/teaching this old skill. Like the gap between generations. It is something, but it is not the preferred way. I want to learn directly, from generation to generation. But I don’t have that opportunity. I wanted to learn straight from my professor, but I did not have that opportunity either because of Covid. But I did have a professor via Zoom. And that is the basis of my knowledge of wool and spinning. Crackled, but good enough. Maybe just as it was before as well?

Manual carding of wool, and pictures sent to the professor during Zoom lessons. Photo Åsne K. Mellem.

Sheep—I looked at Åsne’s pictures and felt softness and warmth. I wanted to hug the wool, press it against my cheek, just be with the wool. I am not good at handicrafts, but I want to learn. I want to understand that moment when you met outside the museum. There, with the wool. How different it is to work with material than to just look at objects in a display case. I am an academic, and I always think I am bad at handicrafts and physical tasks. Yet my fingers race across the piano keys, and I can solve things with my hands when my environment supports it.

“I want to write meaningfully and ethically”

It struck me that it is a difficult task, to regenerate the practice and ways of knowing the wool. Åsne talks about this in her art practice, she has conceptualized it as a “gap of knowledge splitting the old and new generations” (Mellem, 2020, p. 14). For her, as a Kven, the multiple modes of being Kven have been actively marginalized by the Norwegian state in attempts to dissolve the past. Back at the lawn, time was running from me, as the children would arrive soon. And there, out of almost thin air, Åsne appeared. She had an appointment at the museum, and was, as the aforementioned elderly people, curious on what I was doing. I explained my situation, the tools swapped hands, and she explained by showing me that I should try to work against the wool fibers. This small piece of advice changed everything, and suddenly I was producing fluffy bundles, the right way. The guidance I was seeking was suddenly there. And not because someone has transmitted the knowledge through generations to Åsne. The work to figure out the “how” with the wool requires deep engagements with both the pasts and the futures in the present. The past signals that Åsne engaged with overcome time and space.

En tiedä, miksi minun täytyi alkaa kirjoittaa äidinkielelläni. En ole tehnyt sitä pitkään aikaan, muuta kuin kommunikoinnissani siskoni, vanhempieni ja Suomen ystävieni kanssa. Ajattelen päätoimisesti englanniksi, mutta tänään minun täytyi kääntää Åsnen tekstiä norjasta suomeksi. Jotain tapahtui. En tiedä paljon kveenien historiasta, joka hävettää minua. Pystyn lukemaan kveeniä, ja kuuntelemaan kveeniä, ja ymmärtämään. Silti sidoksemme ovat minulle epäselvät, mutta eivät etäiset. We visited the Alta Museum with our students last week. I spent almost all my free time at the museum wandering through an exhibition where people had brought objects to the museum and shared their significance to them—the significance that ties the object to being Kven (til å være kven).

I sat and stood for a long time in front of a small wooden figure that Maureen Bjerkan Olsen had presented at the object event at the museum. Maureen is smiling in the picture, both in the portrait and in another photo on the side where she is holding the figure. She is not just smiling, but laughing, contacting the audience, something is born between them, and the figure is part of it. The figure is wood, and it is history, it is love and care. Maureen’s father carved the figure—he wanted to carve a figure for his daughter, who was so enthusiastic about watching Emil of Lönneberga, where Emil carved. I too watched Emil as a child, and carved a little, and my father taught me to always carve away from oneself. I think of my father and miss him across the border.

The Ruska vain aaret? exhibition at Alta Museum that you refer to, Tarja, is really exciting, and takes me back to my BA project in Art and Craft at the National Academy of the Arts in Oslo, Kven er Kven? (that is, “Who is Kven?”—a really bad pun on the Nynorsk word kven, meaning “who”).

Photo from the Ruska vain aaret? exhibition at Alta Museum. Photo: Tarja Salmela.

The people Gyrid is referring to outside the museum is a phenomenon I meet all around. People who get a “blast from the past” when they see my work. Last week, I visited a nice lady who handed me some materials from her late mother. She had vivid memories from her childhood, of her mother spinning yarn, dyeing wool, creating baskets of roots and bark. But she never did it herself. “Don’t ask me, I don’t know!” was repeated several times, with a small laugh to downplay the fact that she had not learned her mother’s crafts. We met after her mother died two months ago, that’s why she reached out, asking if I was interested in those materials. But I really wished I could have met her mother as well. A lady with knowledge and stories and the urge to help someone she saw struggling with the materials and craft techniques. A lady with knowledge and stories and the urge to help someone she saw struggling with the materials and the craft techniques. And now it was too late, for both of us.

I did not know that much about wool when I met Gyrid that time. But for me, the craft was a current state of mind, something that you do, something to engage in. For the other people mentioned, it is something in the past, connected to their nostalgia.

One of the boundaries I feel meddle in my writing on Kven topics is the political categorization of Kvens as one of Norway’s five national minorities. This is something I don’t know how to address, since political categorization in itself is such an important tool for Kven people in order to take back one’s culture, language, and knowledge practices. It seems like an impossible project, to talk about Kven issues as something that is ordinary and normalized and disconnected from the political side of being Kven. Whenever I have to explain to people what I work with, the questions turn immediately towards what “Kven” means, who they are, what distinguishes their culture, and so on. A bottom line for the inquiry is basically that they need an explanation for identifying what is so special about Kvens, and why should they (as members of the majority society) care? Here, the political status comes in handy, as it sets up a logical framework for people to recognize and accept the need to give Kvens extra attention, support, and resources. When I deliberately try to avoid the framework, I have experienced that my ideas for articles are turned down and perceived as irrelevant. The space for simply being present is limited—the question is how I should participate in making this space less narrow. How can I resist the urge to reflect and go against the constraints that are put in motion?

Elisabeth Stubberud, associate professor at NTNU in Trondheim, once said that when asking her grandmother in Pyssyjoki/Børselv about her ethnicity as either Sami, Kven, Norwegian, or something else, her grandmother responded: “Det er et spørsmål for folk som gjør for lite kroppsarbeid og bruker for mye tid på å tenke” (Stubberud, 2024). This could translate as: “This is a question for people who do too little manual labor and who spend too much time thinking”. This refers to today’s currents, where people are categorizing and trying to figure out what is what. But before, in the past, they just lived, they just created and talked. They did not care about what was what. They did not have to in ways we do today.

“Do I spend too much time thinking?”

Yesterday, Gyrid and I discussed how our conversations and the free-flowing sharing of thoughts create space to address the “normality” that you, Åsne, described in your text. “And I realized that the Kven is … normal. It is everything, it is Finnish, Norwegian, Sami, day to day. It is all about context.” Gyrid shared her thoughts on how, to be able to publish in academic journals, things must be made somewhat abnormal, exceptional, and distinctive to have enough “impact” to be worthy of academic argumentation. Here, we can talk about Kven culture and how cultures must be further “minoritized” through argumentation to become “worthy of research”. Gyrid, you spoke about this so beautifully—I would like to hear more. Why isn’t normal enough? Can this freely evolving dialogue of ours argue for normality—a normality that does not seek something special, unique, but is sufficient as it is? One that recognizes connections to others and literally dismantles previously built fences between “them” and “us”.

Can wool be the key for us to discuss normality? What might flow, current, have to do with normality?

“This back and forth is amazing. Realizing I should write more letters.”

The thought of normality is a huge and interesting topic. Here I’m referring both to Tarja’s Sunday thoughts and Gyrid’s text about ethical writing. And here, wool can play a leading role. You can observe the discussion around normality both in academia, as Gyrid has described, as well as in the majority society, and in the Kven communities. I recently had a discussion with a museum professional in Ofoten. He did not know the difference between the Sami and Kven people, nor that the languages were different (that’s another letter for another time …). Point being, we ended up going back and forth, where I presented him with something Kven, and him saying, “no, that’s Nord-Norsk [i.e., the Northern Norwegian dialect], that’s not Kven”. And then I had to reply, “Even though you haven’t seen the Kven context of your own district, that doesn’t mean it’s super exotic or hidden. It is everywhere, in the details.”

He would not even hear talk of a sauna being Kven, since he had built one himself.

We disagreed on disagreeing.

Footnote: The sauna is somehow in-between here, where in a historical Northern Norwegian context it is strongly connected to Kven culture, but in an international context it is Finnish.

“This took me far from wool, but perhaps wool is still present.”

A downside of normalizing Kven life is then an effect of not being visible for others to see. In doing so, I feel that I downplay or even participate in a cover-up of the significant consequences of the Norwegianization policy that Kven people still struggle with today. The process to gain a more equal position in Norwegian society requires attention towards the past, to establish a common ground that explains why it is important to care for the minority groups, like Kvens, that did not fit into the “national narrative” constructed around the imaginaries of one nation, one language, one people. Also, the continuous focus on the political rights to live a Kven life is concentrated on humans as the bodies with agency to act within the political system. Again, a Kven life is disconnected from the actual life that is surrounded by relationships to the environment. Landscapes, species, materials are not marked as Kven or understood as relevant for being Kven. Sheep, inner layers of clothing, grazing land, skin, wool, fishing nets, place names, wool products, seaweed. The landscape is connected to the human and more-than-human universe. Place-based and situated knowledge is hidden, or simply forgotten in the political frame. The stories we are supposed to tell are not told.

“Another brain dump. Long and messy.”

I did not know much about the current situation of the Kven communities back then, having moved to Oslo and felt alone about my Kven heritage. All I knew was the stories from my grandmother, but she also talked about Jesus, Santa, and mythical creatures. I did not know what was true and what was only fairytales. I started to travel around, asking people in the Kven community about what it meant being a Kven today. The conversations varied from two to seven hours, and I learned to drink coffee because everyone served it during the talks. And I always asked: “Do you have something Kven to show me?” Because I did not know how something “Kven” looked like. And they all pulled up something “normal”. Something I had seen before. A coffee grinder, a rug, a Bible in Finnish. Nothing fancy, And I realized that Kven is … normal. It is everything, it is Finnish, Norwegian, Sami, day to day. It is all about context. The relation the person had to the one who made it. Maybe it was the same person who taught them about their Kven roots. That makes the object Kven in their eyes. But is it enough for a museum? Is it enough for the majority population?

This is the same nerve that the Ruska vain aaret? exhibition is touching upon.

Even the Kvens themselves have a desire to “exotify” their culture. People finding their Kven heritage at the age of 60 have a strong wish to start to dress Kven and not only “normal”. But how does Kven look when you have dressed normal (read Kven) your entire life? I can also find myself in this position. Having the privilege to dress and undress my minority at any point. I can put on silver and shoes, making me Kven (if the people viewing it know the Kven references, that is also a different letter). Or I can wear my sneakers and hoodie and look normal, or Norwegian. But that is also Kven in 2024. Sigh … Here, the Kvens with the Kven language as their mother tongue have an advantage, since they can always throw out a Kven phrase, validating their Kven connection even wearing sneakers or hoodies. That is the privilege I don’t have. Yet.

Are activities like this, that the museum facilitates for younger generations, telling the right stories? Is it courage? Dealing with the past. Reconnecting with the past? Or is it the opposite of courage?

Or is it an opportunity?

Maybe opportunity in a passive way. But by giving kids the opportunity to set the ocean, nature, and yourself in a Kven context, you normalize it. And then they don’t have that need or urge to dive into a mid-life-Kven-crisis at 60 with bling and fantasy Kven costumes.

A passive rebellion of exotification, and that needs courage, because normal is normal.

Kanskje vi må undersøke fisken?

Wool, sheep, and fish. Softness, slipperiness. Roe, bones. The fish’s open mouth and the hook. I was a vegan for half my life, and now I eat both meat and fish. We went fishing the day before yesterday for the first time since my childhood, in Hella.1 I was afraid of catching a fish, but at the same time, I wanted to catch one, so I could justify my current habits of eating fish to myself. My colleague and I are writing about salmon farms, writing about the salmon turning into a hybrid machine that still senses and is part of the sea and the river. We write about the scars and wounds that form on the bodies of intensively farmed salmon as parasites bite them in cramped tanks, and they want to escape. To leap, to migrate, to spawn, to seek fresh water where it would not hurt as much. Tears come to my eyes. I want to catch my own fish from the sea, where it has been able to live freely. Slipperiness, softness, and what about the line? Åsne wrote about nets, and how all the skill that has been invested in those nets that hangs in the boathouse. Is that the state of our times?

“So many currents meet and joins as I read your texts!”

A fishing net for catching sea salmon in Paatsivuono/ Bøkfjorden, hanged up to dry, just harvested for seaweed and other species that become entangled with the net’s plastic fibers in the water. Photo: Gyrid Øyen.

I’m sitting here, drinking my mid-day coffee from a Nuuskamuikkunen mug (yes, I googled “Finnish Snusmumrikken”), reading your thoughts about your chat and where all the threads are leading us. Back and forth, as the tide, as currents, shifting, at some point leading us back to the start. And beyond.

Letters in progress, Tromsø. Photo Tarja Salmela.

Ja minä kirjoitan näitä ajatuksia kahvin äärellä, juon kahvia Muumimamma-kupista, jota keskustelujemme myötä katson tänä päivänä eri tavalla. Moominmamma and the Moomins in general have been a symbol of Finnishness for me since I moved to Norway five years ago, wanting to bring something with me that reminded me of my homeland. Moominmamma may have little to do with wool, fish, and fishing nets, but this train of thought reveals something about the process that began when our paths crossed.

Can we make something both safe and more efficient, like the radio telegraph system in Lofoten supposedly did, when it comes to practices concerned with past looking?

When does the future arrive?

Thoughts begin to connect through even the most unexpected links.

How do we make normal exciting?

Wow. That is a crazy thought and can be an interesting take on… wool.

Seeing wool as normal/exotic/cultural/sustainable/individual. It is all and nothing big at the same time.

Encounters in Moskivuono/Ullsfjord, August 2024

It sticks.

Thousands of tiny, small fragments of boiled lichen.

When Åsne pulls out the different sorts of textile from the casserole on the terrace, chunks of lichen transform themselves from a coherent mass to individual particles. As the textile dries up, it also changes form, from wet, heavy, and dark to dry, stiffer, and with a richness of nuances and shades.

Still, when I touch the textile, or the skein of wool, after it has dried up, the dust of the lichen is present. It makes the surface rough.

“Tipping point.”

Although the lichen is the component that contributed to the dyeing process, it must disappear before the materials are, again, transformed and displayed as art pieces in an exhibition. The presence of the lichen, its traces, somehow disturbs the “white cube”, the cleanness and the expectations of the room.

I find it unfair.

Tarja told us how the lichen never appears alone. It leans on others, like us.

Now, after it has been located, collected, boiled, and tossed out, where does it go?

Lichen-colored wool. Photo: Åsne K. Mellem.

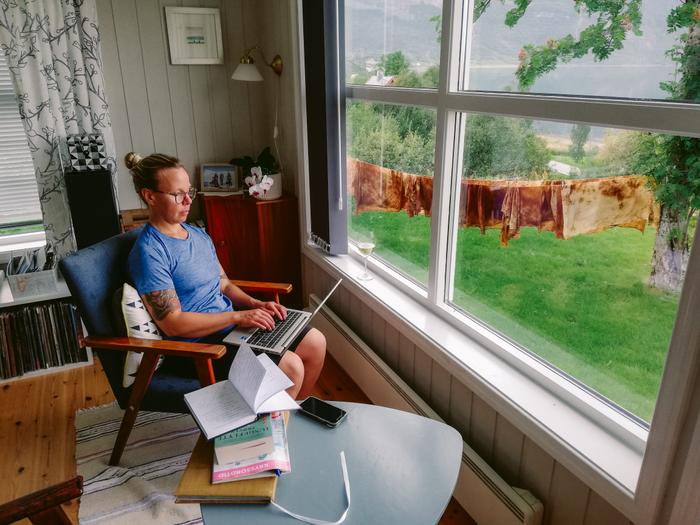

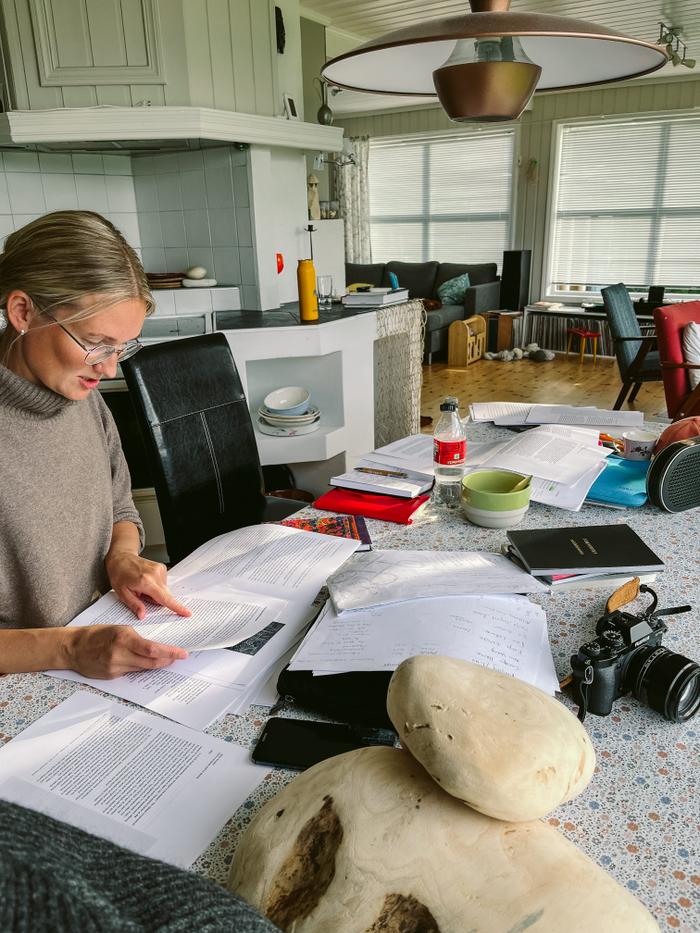

This is our third day at Åsne’s family’s second home at Hjellnes in Ullsfjord. The fjord has three names: Olggosvuotna (Sámi), Moskivuono (Kven), and Ullsfjord (Norwegian). A 75-kilometer-long fjord that flows northwards, from Sjøvassbotn and along the west side of the Lyngen peninsula, has been a place for us co-existing in time and space. The dinner table is flipped, so the long side of it is facing the window. In that way we can all face the view out in the fjord while writing and talking, instead of facing each other across the table. We look at the view filled with steep mountains and the ocean. This is the view that has also been the backdrop for anyone living here, or visiting, for centuries.

Our collaborative space in Ullsfjord. Photo: Gyrid Øyen.

I’m used to working alone. Collecting, prepping, dyeing wool.

Processing pieces of wood. Seeing how things turn out,

what to discard, what to bring further into my practice.

It’s messy.

I rarely invite people into my process.

When trying to reflect upon why, I often conclude with the messiness.

It’s dirty, I’m dirty.

If you want to join you will get dirty as well.

But it might be a layer of insecurity in it as well?

Because the dust and the goo are only organic.

It’s not dangerous (but wear a mask when grinding) or permanent, it’s only nature.

Maybe it is me as an artist, at my most vulnerable.

In a space between an idea and a finished piece,

a space where nothing is certain, and everything can happen.

If I get any feedback now, the idea turns into a fact.

Dyeing is a messy process I. Photo: Tarja Salmela.

Dyeing is a messy process I. Photo: Åsne K. Mellem.

We started out as individuals, writing letters. Three different fields of work, knowing, not knowing each other. Then we meet, we spend time, connect through conversation about work, about life, about nature, picking blueberries. Just being in the same space and time. So far, our connection has been facilitated by digital communication tools (digital letters, two Teams calls, Messenger group, and e-mail), and partial face-to-face encounters. With partial, I refer to meet-ups between two of us, after which the third one of us has been updated about the meet-up.

This is also the day when Gyrid and I return home, while Åsne stays here at Ullsfjord. We have come to think of the meaning of our collaboration during these past days, including thinking of the meaning of collaboration in general. Our discussions, whether over a glass of wine or when picking juniper or blueberries or tasting a freshly baked bread, have made us realize that this collaboration was never motivated by an aim to publish a paper. It was motivated by an interest to learn from each other, and from each other’s ways of working.2

--- I somehow feel that my perspective has been distorted.

It is easy to write letters somehow, where you don’t see the recipient,

but you feel a connection.

Suddenly we are together, at the same place, sharing an experience.

Gyrid and Tarja sitting at the next table.

How do you write letters to someone you can just talk to?

Realizing this is a text about text.

My back hurts, my legs itch.

I want to run away from the screen, although I don’t run.

It is comforting to know that we are all in the same boat, with the same goal.

We need to stick together.

If I was alone, and didn’t have the right feeling,

when starting on a letter, I would probably leave,

postpone.

To sit this long is something I could not do in the presence of someone else.

2

Dyeing is a messy process II. Photo: Gyrid Øyen.

It is deeply inspiring to be present in another person’s creative processes. The proximity of working with wool, of gathering the materials needed to develop color, like juniper. Feeling the resistance or the willingness in the branches of the tree, to be picked. How the pine needles let go and meet in your glove, before they go into the bag. Also to fold different lengths of textile, to feel the variations of stiffness or softness, or both combined. To tie, to rearrange textiles, the possibility to play with nuances in the fabric, done by other elements like the juniper pines. Working with materials allows you to get close, to observe, to touch, to smell, to interact in so many ways. Can an academic writing process strive towards an openness like this? Can museum practices open the innermost chambers of objects in the same way? In some sense, this is connected to ‘the whom’ we open for. It reminds us of how complex interactions are, because there is always someone else involved in what we do. Nothing does itself, Haraway (2016, 2019) reminds us. Although we all have sat too long behind our desks, we still must (and are able to) return to the desk, to the writing, to this, to open up, to be transparent, to display our threads and processes and motivations.

In the writing process, I often feel alone.

I long for a community,

for others to respond, to push, challenge, question, and support the work.

There’s a fine line between the need to be

responded to, pushed,

challenged, and questioned,

and the need to be alone,

to think without confrontation,

to let ideas swim.

The process is different as a museum practitioner,

inviting a class of children into the museum, not knowing how the process will evolve.

I might have a plan, an idea,

a practical activity connected to the past, to knowledge, to the surrounding landscape, to language.

But I need to go with the flow,

listening and tuning in with the crowd,

to see where the attention turns.

The process is open, and closely performed together with others,

yet I feel detached from deeper reflections

about what plays out in front of me.

I enjoy the fact that we think in different ways, on our last day here together. We are tired and notice that we feel a slight push (in addition to pull) to finish something—to find coherence in something. How can you finish something that started to grow without clear intention? Gyrid, I read you, and can smell the soup of boiled lichen, and boiled juniper. Your attention to the materiality of lichen-wool, and perhaps the less desired part of its materiality—the dust—brings me back from aiming to form a cohesion. Perhaps it brings me back to the experimentality of our collaboration—how we never really did know where this path would take us. It is unfair that the dust does not fit the perception of an art exhibition. It also draws our attention to the unnaturalness of the exhibition space itself.

To dye materials such as lichen, juniper is collected and boiled.

The materials become gooey when boiled, and dusty when dry.

Shaking a newly dyed canvas makes it all stick to your skin, your hair.

The lichen stays under your fingernails for days,

popping out of your socks when you undress for the night.

And also the processing of wood.

It’s dusty.

The grinding creates a layer of dust everywhere.

Before Tarja and Gyrid arrived, I washed up,

removing grinding dust from my armpits,

picking lichen out of my belly button.

When presented in a gallery, it’s clean.

The mess is washed away, the wrinkles are ironed, my hair is combed back.

When does something go from process to becoming art?

When does a draft become a set text?

Pehmeä paaro, piece in the exhibition (Sinne) Käsin, Vigelandmuseet, 27 September 2024–12 January 2025. Photo: Vegard Kleven, Vigelandmuseet.

Unmessiness: Ironed wrinkles. Photo: Vegard Kleven, Vigelandmuseet.

Where does the lichen go when it has been tossed out?

Chunks of lichen mess dipped from buckets to the grass.

I would assume it has numerous nutritious benefits for life forms inhabiting that “dip space”.

Tipping point!

That lichen will continue its life as a metamorphosis. Åsne?

Can the dust teach us something valuable about staying close?

Closer than what’s comfortable?

Like now, being friendly, forced to write together,

to each other, at the same table,

in front of the same view.

Weaving knowledge with technology. Photo: Gyrid Øyen.

Our motivation has centered around wool—as an entangling materiality—which has now also been afforded, by us, by the qualities of a magnet. Wool brings us back to the “something”, like a magnet that is not too strong but allows the actants of its assemblage to move and weave new threads, yet it retains its power to “bring back”, to assemble. With wool, we had played with time, already in our letter writing: assembling our letters in what was back then, in the moment of writing, the future—returning to the past, in the current, only to know that what is to come will be yet another return path (Nakai, in this volume) to what once was. To write letters became a way to swim in the currents, currents that hold the elements of materiality and temporality and propose the situated nature of our knowledge (Haraway, 2016; 1997).

Tools of collaboration. Photo: Tarja Salmela.

Tools of collaboration. Photo: Gyrid Øyen.

Thus, we have come together through letters, and grown from wool into intention, to physical proximity and continued to write letters, like we do now. Letters are our way of connecting with the past, present, and future. Letters have become a way to swim in the currents; to dive deeper into the murkier layers of the ocean that reveal something new about each other, about our connections with each other, and the ways in which we aim to make a difference to the world—to make it a little bit better place to live for generations to come. As such, letters can take many forms. A verbal exchange of letters in an intimate space can take the form of a deep conversation, where everyone has their say, without competing for their place in that space. Don’t get us wrong—this is not easy, nor always pretty. No proximity exists without tensions, disruptions of harmony. For us, there has never been harmony.

We guess this is the essential motivation for our collaboration. Something grows from what emerged meaningful to us, to perhaps inspire somebody else to open for the possibility of a materiality (wool or something else, perhaps electric cables, stone, or wind) to pull together.

Picking up threads from each other, through encounters in letters and in embodied presence, reminds us of Kari Steihaug’s work Arkiv: De ufullendte [Archive: The Unfinished Ones] (2011), an assemblage of unfinished knitting projects which Steihaug beautifully describes as a “tribute to incompleteness”. Collecting unfinished knitting projects throughout the years from people and returning them to the ones who want them back after being registered to the archive, Steihaug expresses the beauty of incompleteness and the art of picking up threads to carry on. Working with memories, stories, and new and past beginnings, De ufullendte reminds us of the ways in which wool becomes something through active involvement with it, of actively relating with it, becoming the possibility of new stories to be created and old ones to be fostered and brought to life. It was wool that brought Steihaug’s work into our awareness, through a seemingly incidental conversation about wool. It happened over morning coffee with people who were unaware of our journey with wool before that moment, and who connected us to a project of incompleteness. Another string spun, plied, weaved, or perhaps knitted. Picking up threads like these has led to our stories that emerge in the exchange of letters not being presented in a chronological manner. This has connected us across space and time, and to become curious about where the letters lead us.

Furthermore, wool has allowed us to engage with “the field” in new ways. Kristen Sharp (2022) has written how fieldwork in artistic practice is “a process of composing, presenting and encountering the artwork in an exhibition or performance context” (p. 51). Fieldwork does not end with the field, nor does it start from it: fieldwork is “not something contained … something undertaken prior to making a work—but rather … something that unfolds out: it returns, it forms. As a material and embodied encounter, fieldwork brings out new understandings through listening, reflecting, acting and creating” (p. 51). Where does our wool get encountered? Where do we encounter wool? Should we bring our Moomin cups?

Wool has provided us with pusterom—a space to breathe—as Laura Põld had created in her artwork “Nende Juuret Läbivad Kivi” (in the exhibition Down in the Bog: Hibernation), space in-between roots, rocks, matter, the living, the dead, all inhabiting the space underneath the Earth’s surface. Like holes in the fabric and organic matter, pusterom perhaps allows us to give up on an effort to make a breakthrough contribution to a specific academic field, feeling suffocated by the box one tries to fit in. Pusterom to find the value in the less remarkable, yet generative and meaningful, through practices, ideas, threads. Wool breathes, and it allows the skin to breath. Why suffocate?

Wool has also allowed us to discuss Kven culture and nature, but also much more. We have not wanted to be restricted by a choice to form such a focus. Here, wool has enabled such possibilities: it has taken us back to what needs to be said, not what is expected to. It has opened paths to discuss what measures normality and exotification, its meaning and its consequences. It has made it possible to discuss the limits of language, as well as the kinds of understandings of the world and its events that arise through our language. In this way, wool has become a language. In her introductory essay to this volume, Halland (2024), after interpreting our collective work, listed “wool” as one of the languages through which ideas regenerate. She has heard us, and she has heard the wool that makes “us”.

In addition to being a language, wool has also become the current. It is in this way, and through perhaps unexpected ties, knots, and connections, that wool is also watery materiality—despite its rather “airy” character. This is why we want to discuss the tide and its different wordings in Kven, Finnish, and Norwegian language. Ebb - ulli - vuoksi - flo - tide - sokku - luode – fjære. These powerful wor(l)dings take us back and forth in the dialogue, weaving together pieces of stories, anecdotes, questions, and/as strings of wool that have now become also watery webs of meaning-making.

This experimental process and production of knowledge creates something new from something old. Like a rag pile of worn and torn out pieces of knitwork, the threads and fibers can still be recycled. Shredded. Spun over again, re-creating the past, like “shoddy”; Sundbø (2019), a Norwegian shoddy fabric owner and textile designer, describes the process of shoddy, turning a rag pile into reclaimed wool. Shoddy makes you conscious about the love, care, and creativity that exists within the threads. Leftover textiles then have the potential of being transmitters of knowledge from the past to the present to the future, like our letters.

When is your time to write a letter?

Cixous, H. (1976). The laugh of the Medusa. Signs: Journal of women in culture and society, 1(4), 875-893.

Halland, I. (2024). ATTENTION: Currents. Metode 3 (Currents). https://metode.r-o-m.no/en/articles/essay/attention-currents

Haraway, D. J. (1997). Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium. FemaleMan_Meets_OncoMouse. Routledge.

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin with the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Haraway, D. (2019). Revisiting Catland in 2019: Situating denizens of the Chthulucene. Auto/biography studies, 34(3), 385-386.

Mellem, Å. K. (2020). I never learnt my mother tongue [Master’s thesis]. UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

Sharp, K. (2022). Open fields: Fieldwork as a creative process. In B. Crone, S. Nightingale & P. Stanton (eds.), Fieldwork for future ecologies: Radical practice for art and art-based research. Onomatopee 225.

Stubberud, E. (2024). Rotete identifisering: Kvensk og samisk tilhørighet i et flerkulturelt samfunn ved Porsangerfjorden. In T. Kvidal-Røvik, K. Olsen & S. R. Mathisen (eds.), Tuulessa: I vinden (p. 56-81). Universitetsforlaget. https://doi.org/10.18261/9788215067797-24-02

Sundbø, A. (2019). Koftearven: Historiske tråder og magiske mønstre. Gyldendal.

Åsne Kummeneje Mellem, Tarja Salmela, Gyrid Øyen, “Weaving knowledge: writing letters with wool,” Metode (2025), vol. 3 ‘Currents’

When the personal histories unfold through writing letters about wool, time-aspects become irrelevant.

- Miriam Sentler

The act of writing in our own language is brave. It reminded me of how long I have not been writing in Chinese and how I never include Chinese in my academic writing.

- Yueyang/Yut-Jeong Luo/Lo

I ended up translating the texts into my native language with Google Translate, and the sentences that didn’t really make sense also added to the experience. Being able to get a glimpse of what was happening based on the context, made it more interesting.

- Ann Wang/以琳 王