It’s cool in here. It’s quiet. It’s still.

The air is sterile and clean, assiduously filtered by machines in some distant basement that maintain the humidity within internationally established levels and circulate it imperceptibly. To make it somehow abstract. The clunk of a reinforced door recessing into its airtight seal transmits through the concrete floor. Not a single hair on our heads is disturbed, no dust lifts on the scrubbed air. The attendant counts ten people into the huge room. Automatic lights respond and flicker on in sequence around the curve of the hall.

Outside, inaudible, “Windstorm Poly”, the fiercest summer storm on record, is pulling trees up at the roots across the port town of Rotterdam, Europe’s busiest harbour.1 150 km per hour winds, barely imaginable in here, despite having just cycled through them, are at this moment killing two people and causing one hundred million euros in property damage. Ten people in blue Tyvek® shoe protection are quietly watching me. I connect a seismic microphone to exposed metal, I can hear voices with it, words muffled, transmitted through the material of the building. I start recording with the camera.

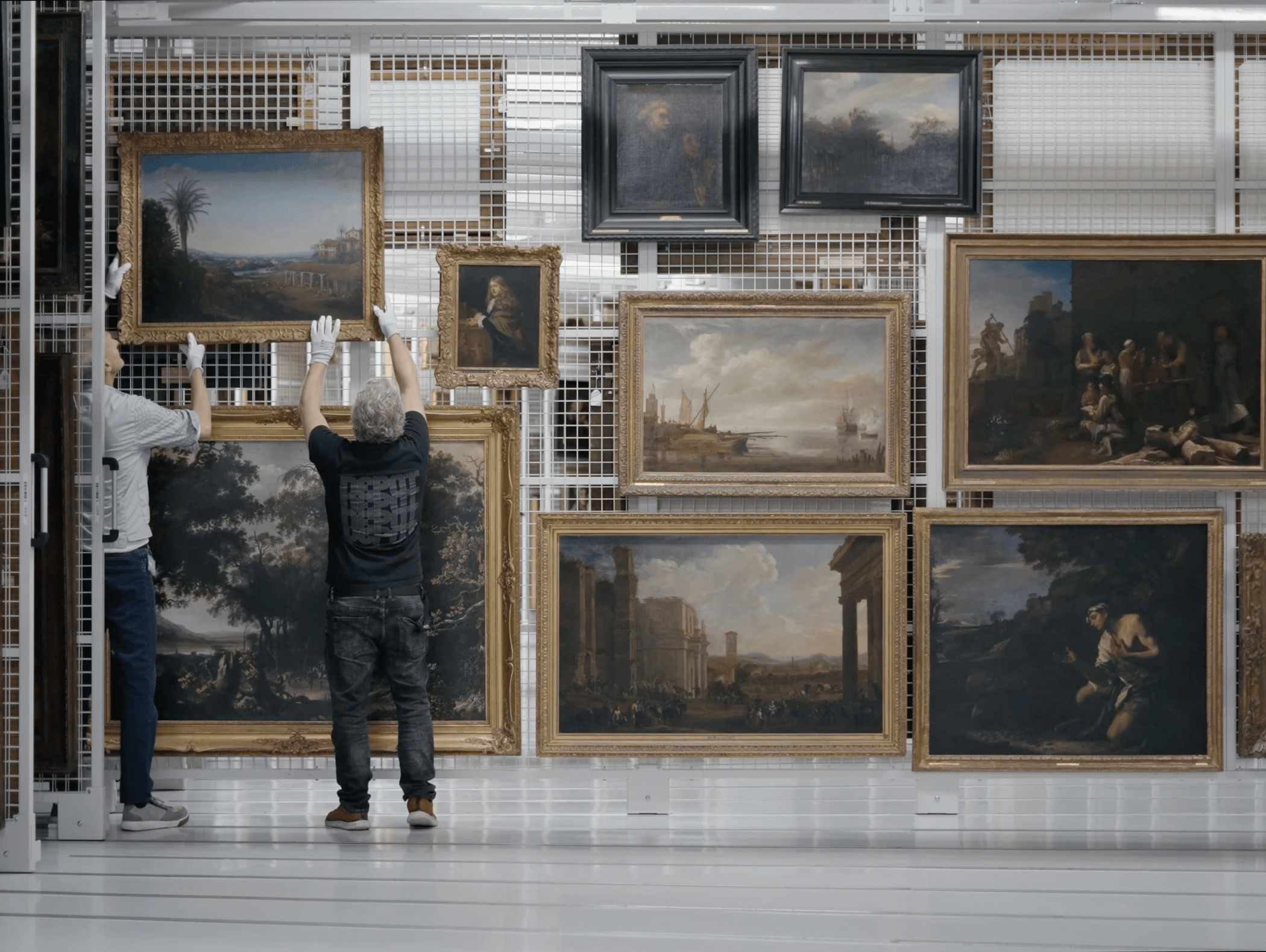

Two technicians in soft-soled trainers walk into the curved hall, counting. They gently pull open one of the huge rail-mounted rolling storage racks. Dampened bearings minimise vibration, but still the sound is shocking as chains rattle against the white powder–coated steel grid. The rubberised wheels mumble on nylon bearings through the seismic microphone from their recessed floor track.

I am in the Depot of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam to see a painting. The technicians lift it down for me and carry it to an easel. The height difference between the two of the them is comical for a brief moment as one strains to reach up and match the grip of the other, who casually holds the frame at its middle with white cotton–gloved hands. Their jeans dissolve into a forest landscape below. Saints agonise around them, their eyes turned to God, hands pressed to breasts. An aristocrat pouts below his flowing golden fringe. A ship holds its position on mirror-still water. Towering clouds hang pendulous over low-lying horizons, peach, pink, green, luminous blue-cast dawn and dusk light spills off skies and reflects in the polished floor.

White foam pads secure the gilt frame on its easel. To the right, from a small frame, a pale-faced young merchant dressed in black looks directly at the camera, his white face cut from a black background. Jesus lifted from the cross is covered up behind the painting, and to the left a simian-faced Christ in a rose-coloured shirt casts an unfocussed gaze from one void into another. The frame of an Italian landscape through which a young man pursues a woman lines up perfectly with the roof of the sugar mill in the painting the technicians have carried for me. Another Jesus disappears into the reflection on his varnish above, and tucked behind the rack, another, carved or painted in something white, leans his head back to plead from the cross. The virgin peppers the scene; receiving the divine ray of light; seated with the infant god; lifting his body from the cross.

The painting I have come to see is a landscape. The horizon sits just below the centre line of the canvas, above it a hazy sky with scattered cloud fades from yellow to blue, reflected in the lakes and rivers that recede into the distance below. The viewpoint is roughly equivalent to the level of the second floor on buildings halfway up the well-lit hillside on the right side of the image. On the left of the painting a thicket of bushes and trees, punctuated by a vibrant red flower, partially conceals a more dilapidated building and hosts a menagerie of birds and a large snake, coiled and eating the bloodied body of an animal. The middle distance is populated by many small figures at work, each smaller than the birds tucked into the bushes, differentiated into type by dress and by skin colour. They work at a distance such that the observer, if truly at this floating viewpoint, may just be able to make out the loudest cries and shouts of their work over animal calls from the encroaching thicket.

The figure closest to the viewer, though still in the middle distance, is dressed in a white shirt and wide blue skirt, she has her back turned towards us and walks with two small children, who are either holding her hand or helping her to carry a bundle of sugarcane. Her skin is rendered in dark paint. The two children, wearing just white shorts, are rendered in paint a trace of a shade lighter.

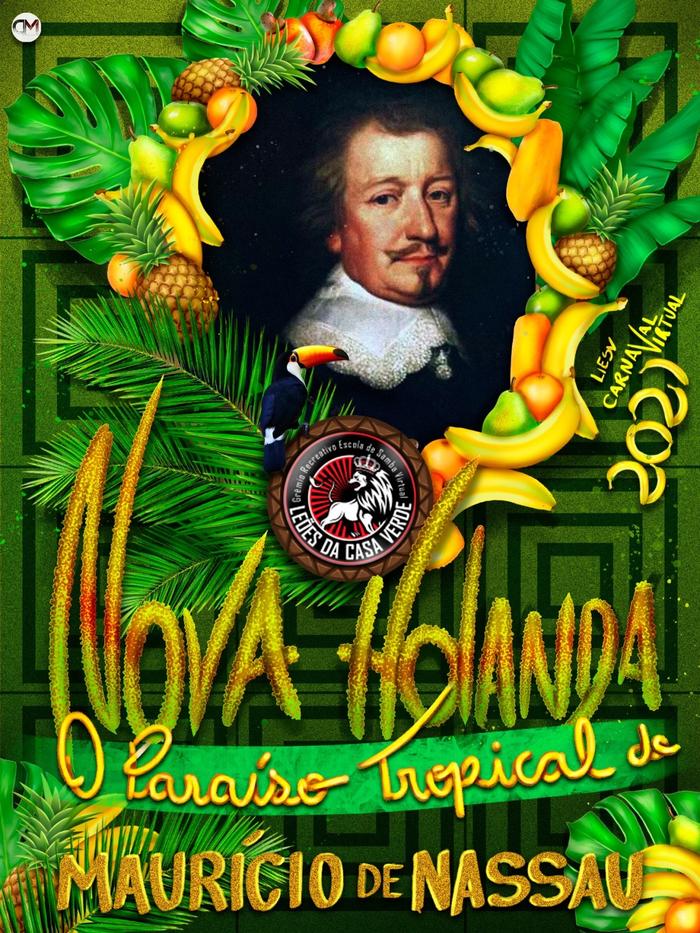

The facticity of the label on the painting’s frame – the name: Een Suikermolen in Brasile (A Sugarmill in Brazil); the artist: Frans Post; the date: 1660; and the donor: bequeathed to the museum by B. de Geus van den Heuvel, 1938 – place it into the realm of the technical, the instrumental. It shows a scene conforming to the conventions of Dutch landscape painting, the theatrical staging of space, the waters, the stillness. Yet here, projected onto this stillness, is a fantastical tropical melange: climbing plants, crouching beasts and writhing snakes, and in the centre of this tropical projection, the processing mill of a sugar plantation. A plantation in Pernambuco, Brazil, painted in the Dutch city of Haarlem, overseen from the top of the well-lit hill by the plantation church, operated through the forced labour of enslaved African and Indigenous peoples by Dutch planters.

Later, in the employee break room, Lisa, the curator of education at the museum, who has organised my visit to film at the Depot, will tell me about their debate on whether to return the painting to display.