Manna, Jumana. Substitute. Forthcoming, 2025. Statsbygg.

Manna, Jumana. Substitute. Forthcoming, 2025. Statsbygg.

Akersgata 44 through aerial images. Edited by Alena Beth Rieger. Montage of Aerial Photographs and Satelite Images. Norge i bilder.

Bugge, Adrian. Rester etter Y-blokka. Photograph. 28.03.2021. yblokkfoto.no

Bugge, Adrian. Klokka tikker for Y-blokka, Støtteaksjon for å bevare Y-blokka. 4. mars 2020. yblokkfoto.no

Bugge, Adrian. Øvre del av trappeoppgangen til konkylietrappen er revet opp og kuppelen falt ned i trappeløpet. Riverester med biter av tregelenderet fyller etasjen under og skjuler selve trappen som virker som har vært intakt helt til nå. Photograph. 29. september 2020. yblokkfoto.no

Unknown Photographer. Team Urbis and Nordic Office of Architecture’s A-blokken Under Construction. 2024. Statsbygg.

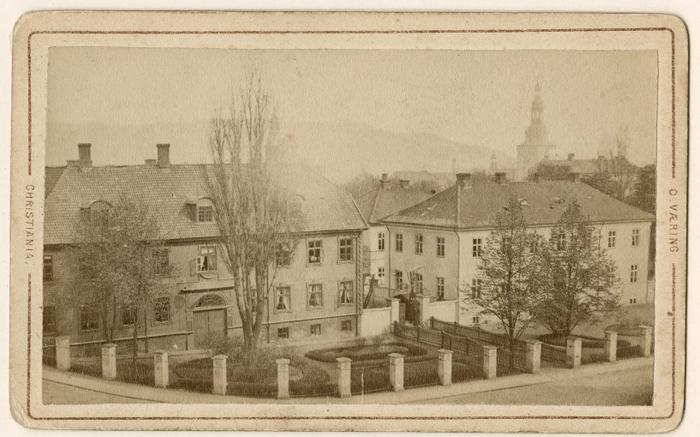

Unknown Author. Rikshospitalet, Militærhospitalet, hage. Photograph. 1905. OB.F10866a. Byhistorisk samling, Oslo Museum.

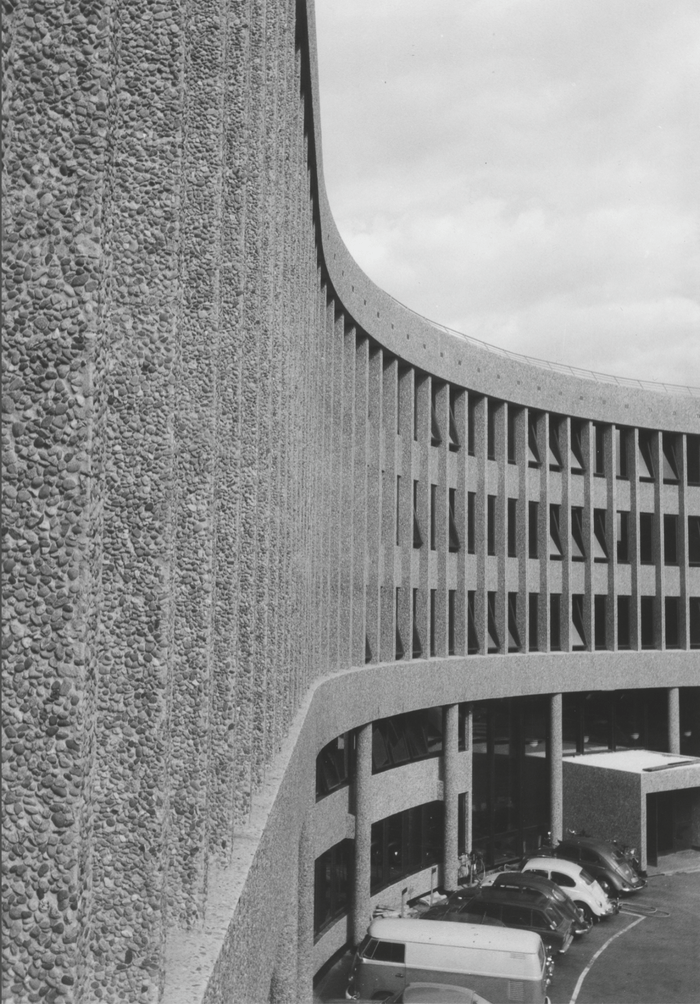

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringskvartalet. Photograph. c. 1969. DEX_T_2903_007. DEXTRA Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/011012600274/regjeringskvartalet

Team Urbis and Nordic Office of Architecture. Regjeringskvartalet. Statsbygg. https://www.statsbygg.no/prosjekter-og-eiendommer/nytt-regjeringskvartal.

Martin Årseth, Tor. “Her fjernes en stein fra muren i Namsos – skal brukes til noe helt annet: – En viktig del av byhistorien.” Film Still. 30.08.23. https://www.namdalsavisa.no/

Manna, Jumana. Substitute. Forthcoming, 2025. Statsbygg.

Y-blokka [Y-block] was constructed in 1969 and demolished between 2020 and 2021. The building, along with Høyblokka (in background) was designed by architect Erling Viksjø.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringskvartalet. Photograph. c. 1969. DEX_T_2903_008. DEXTRA Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/011012600276/regjeringskvartalet.

Militærhospitalet was constructed in 1807 and deconstructed between 1954 and 1962. It was reconstructed at Grev Wedels Plass between 1982 and 1984.

Fotoatelieret. Hospitalet. Photograph. 1983. T001_03_0538. Riksantikvaren.

The Tulip pattern can be seen on the column to the right of the photograph.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringskvartalet. Photograph. 1958. DEX_T_4437_054. Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/011012601199/regjeringskvartalet

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringsbygget. Photograph. 1958-59. DEX_T_4420_001. DEXTRA Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/0210111807291/regjeringsbygget-ark-viksjo-modell-og-nybygget-58.

Lundén, Åsa. Jumana Manna’s Government Quarter Study. Installation view, Nordic Pavilion, Venice Biennale. Photograph. 2017. https://www.jumanamanna.com/Government-Quarter-Study.

Manna, Jumana. Substitute. Forthcoming, 2025. Statsbygg.

In Classical Latin, spolium referred to the stripped hide of an animal, and spolia, plural, a violent retrieval, such as the spoils of war.

Messier, C. An Ionic capital embedded in the south wall of the Church of St. Peter at Ennea Pyrgoi, Kalyvia Thorikou, Greece. Photograph. Undated. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=72813483.

Hart, Niklas. Construction of Jumana Manna’s Substitute. 2023. KORO.

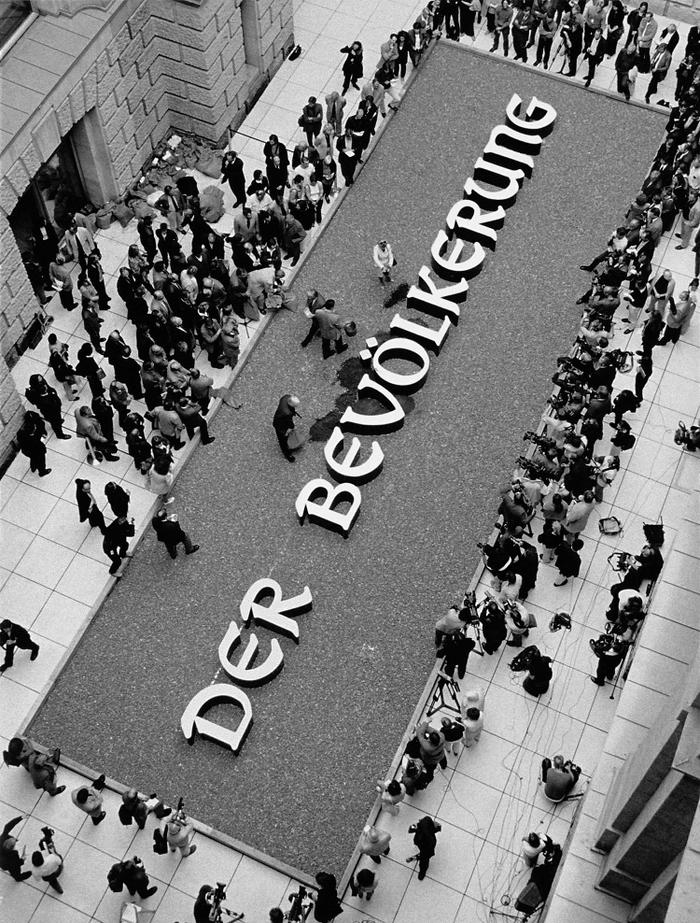

Liebchen, Jens. Hans Haacke’s Der Bervölkerung. 12.09.2000. VG Bild-Kunst. https://derbevoelkerung.de/.

Screenshot from google maps street view. 09.08.2023.

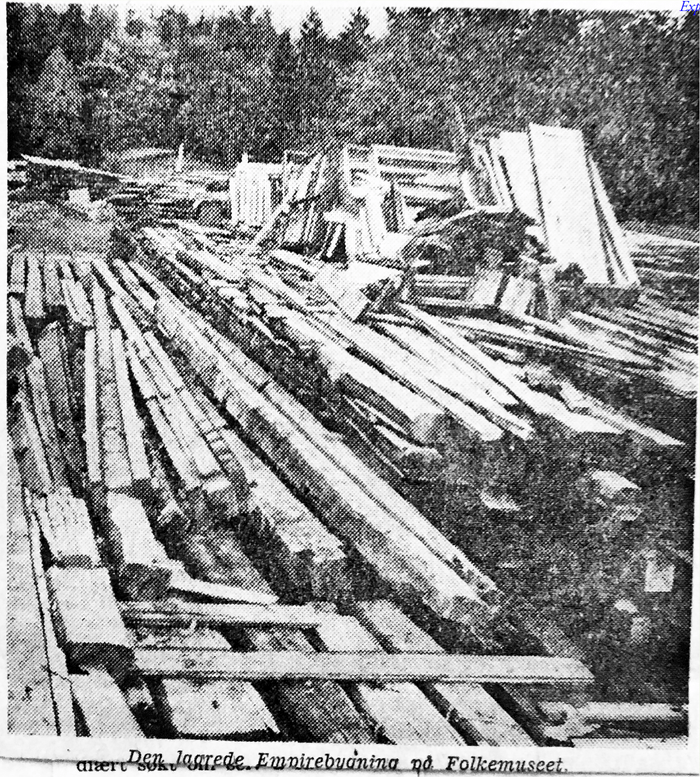

Newspaper Clipping showing Militærhospitalet in storage at Norsk Folkemuseet. 195x-1962, RA_PA-0573_E_Ea_L0001, Riksarkivet.

Fotoatelieret. Militærsykehuset. Photograph. 1982. RAPL.F6x6-14 (label partially obscured). Riksantikvaren.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringskvartalet. Photograph. c. 1969. DEX_T_2903_013. DEXTRA Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/011012600292/regjeringskvartalet.

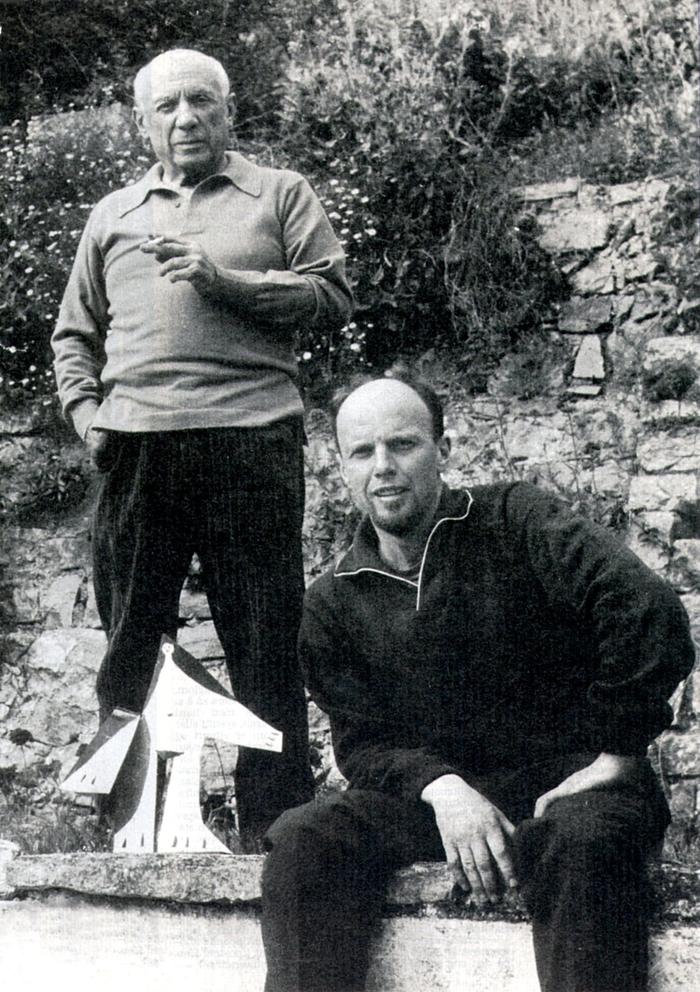

Picasso and Carl Nesjar with the folded sheet metal model painted for the sculpture built at the property of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler in Essone, Chalo-Saint-Mars, France. Photograph. c. 1961.

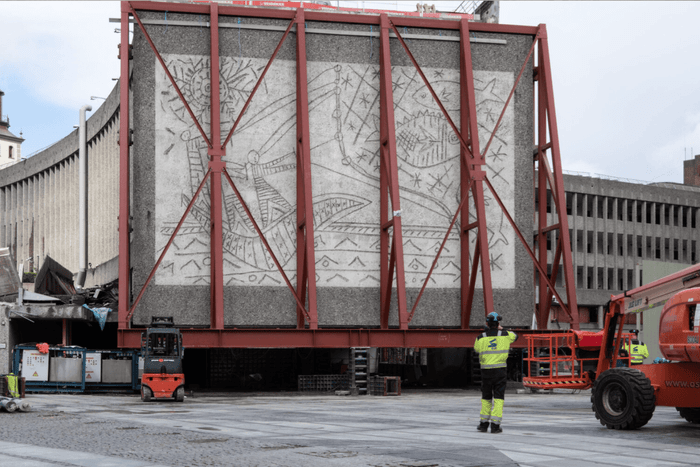

Bugge, Adrian. Ny bit skåret ut og løftes bort. Photograph. 14.07.2020. yblokkfoto.no

Bugge, Adrian. Fiskerne senkes. Nå skal den ikke lavere. Arbeider fotograferer dagens jobb. Photograph. 29.07.2020. yblokkfoto.no

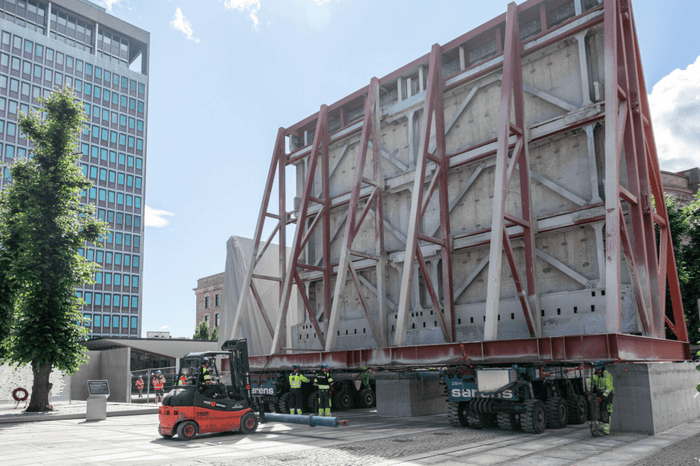

Bugge, Adrian. Den 250 tonn tunge veggen har nådd fundamentet der den skal stå i lang tid fremover. Her ser man baksiden som er forsterket med metall. Det røde stativet derimot skal fjernes og det skal bygges en monter til den på stedet. Photograph. 30.07.2020. yblokkfoto.no

Bugge, Adrian. Den 250 tonn tunge veggen beveger seg over regjeringsparken. Photograph. 30.07.2020. yblokkfoto.no

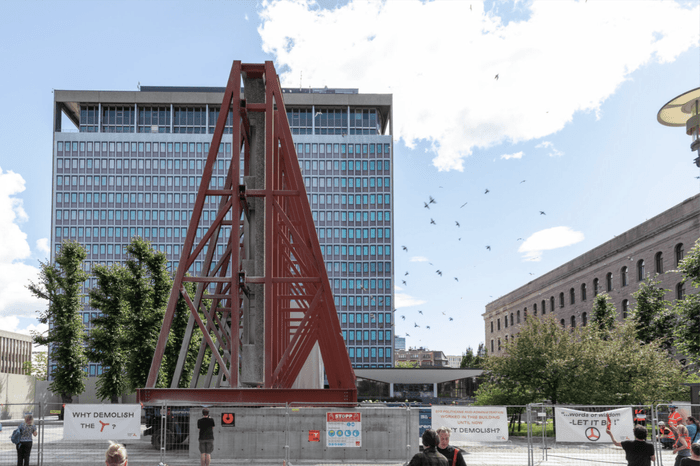

Bugge, Adrian. Fiskerne og Måken bures inn for så å tildekkes. Planen er å lagre dem her til det nye regjeringskvartalet er bygget, men det er det ikke engang bevilget penger til, og det er juridiske uenigheter om veggene kan plasseres på det nye bygget i det hele tatt. Selv hvis det går etter planen vil de fort stå tildekket i ti års tid. Photograph. 12.08.2020. yblokkfoto.no

Unknown Photographer. New Regjeringskvartalet Under Construction. 2024. Statsbygg.

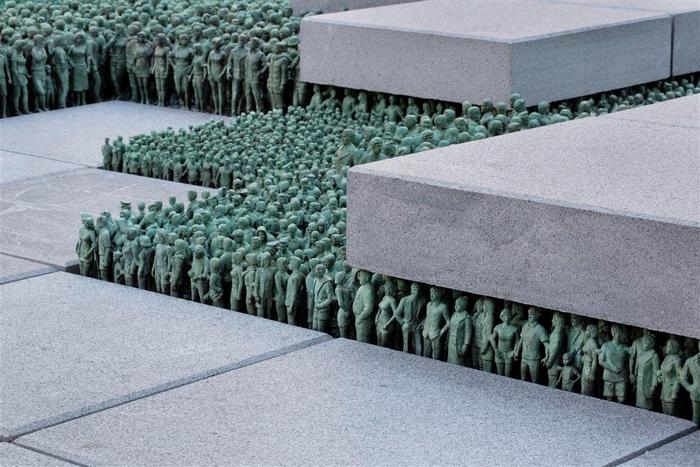

Isaksen, Trond A. Do Ho Suh’s Grass Roots Square. 2012. KORO.

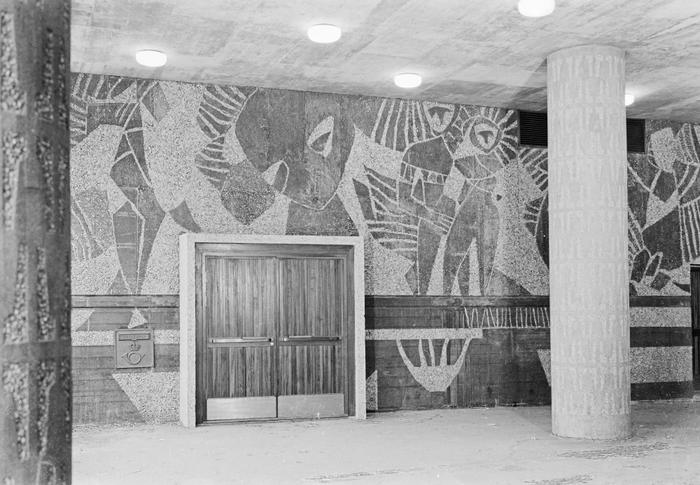

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringskvartalet with Inger Sitter’s wall piece. Photograph. 1958. DEX_T_4437_054. Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/011012601199/regjeringskvartalet.

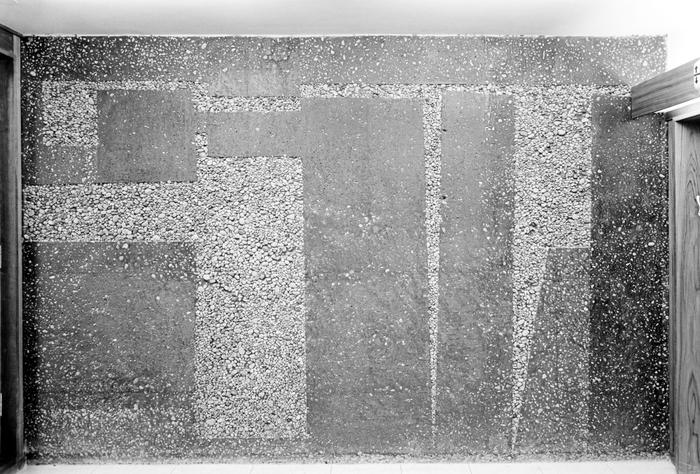

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringskvartalet with Kai Fjell’s wall piece. Photograph. c.1958. DEX_T_4437_045. Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/011012601184/regjeringskvartalet?query=kai+fjell&pos=2&count=348.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringskvartalet with Odd Tandberg’s wall piece. Photograph. c.1958. DEX_T_4437_048. Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/011012601188/regjeringskvartalet.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringskvartalet with Tore Haaland’s wall piece. Photograph. c.1958. DEX_T_4420_078. Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/0210111807332/regjeringsbygget-ark-viksjo-modell-og-nybygget-58.

Collection of written protests against the demolition of Y-blokka. Compiled by Alena Beth Rieger. Plan og Bygningsetaten.

Bugge, Adrian. Vake for Y. Arbeider fotograferer dagens jobb. Photograph. 20.09.2020. yblokkfoto.no.

Bugge, Adrian. Det triste resultatet av dagens intensiverte riving. Se bilder av den voldsomme prosessen under og en video i den nye video-seksjonen. Photograph. 27.08.2020. yblokkfoto.no.

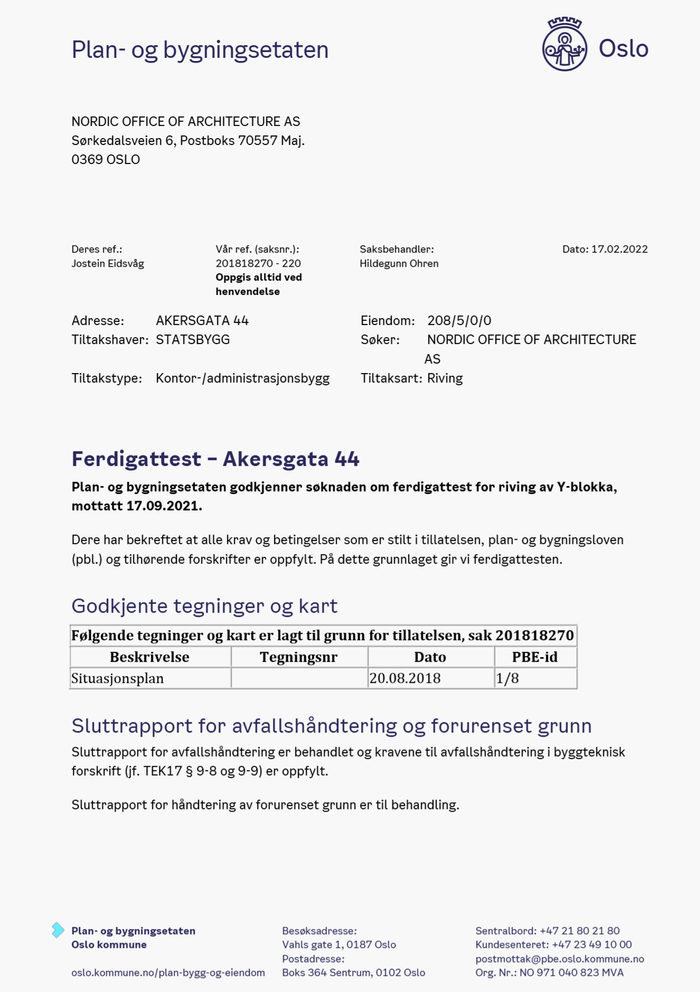

Ferdigattest – Akersgata 44. 208/5/0/0. Plan og Bygningsetaten.

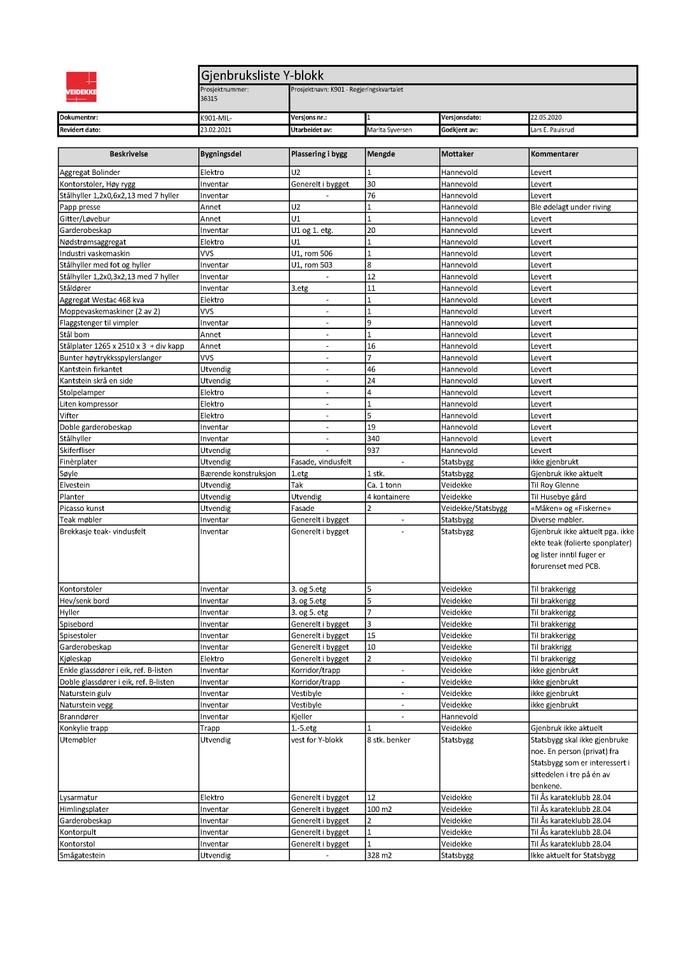

Gjenbruksliste. 208/5/0/0. Plan og Bygningsetaten.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringskvartalet. Photograph. c.1969–72. DEX_T_2903_001. Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/011012600238/regjeringskvartalet.

Ludwik Szacinski. elv, foss. Photograph. 1908. OB.SZ18439. Byhistorisk samling, Oslo Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/011012600238/regjeringskvartalet.

Unknown Photographer. Y-blokka. Photograph. c.1969–70. Nasjonalmuseet. https://www.nasjonalmuseet.no/en/stories/explore-the-collection/The-Y-block/.

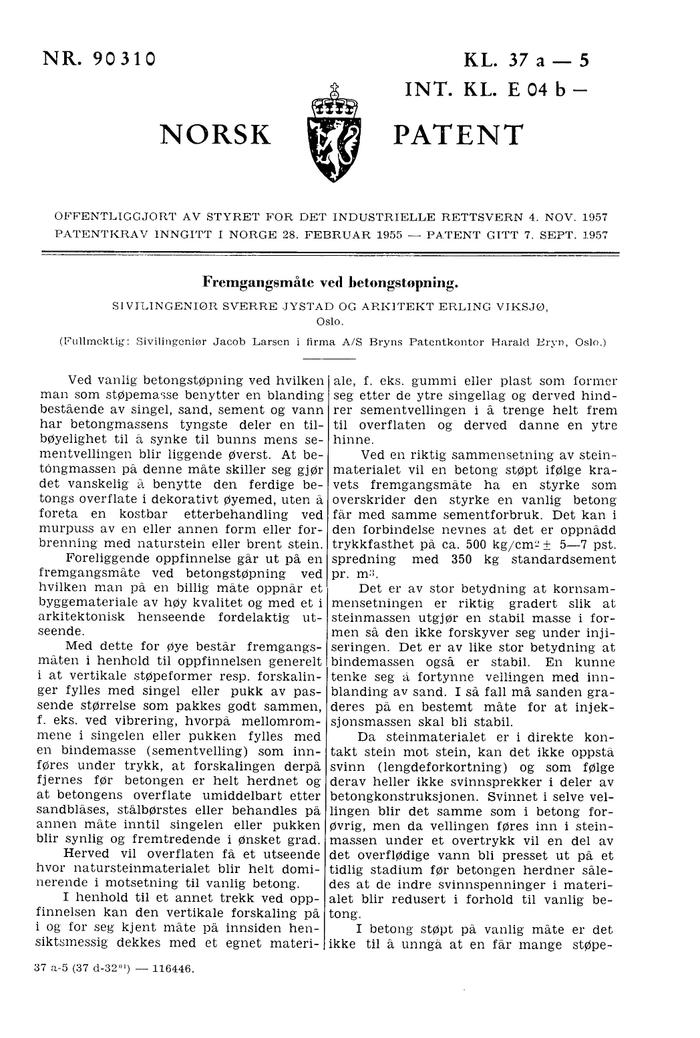

Jystad, Sverre and Erling Viksjø. Patent 90310. The patent was applied for 28. February 1955, and approved 7. September 1957. Norsk Patent.

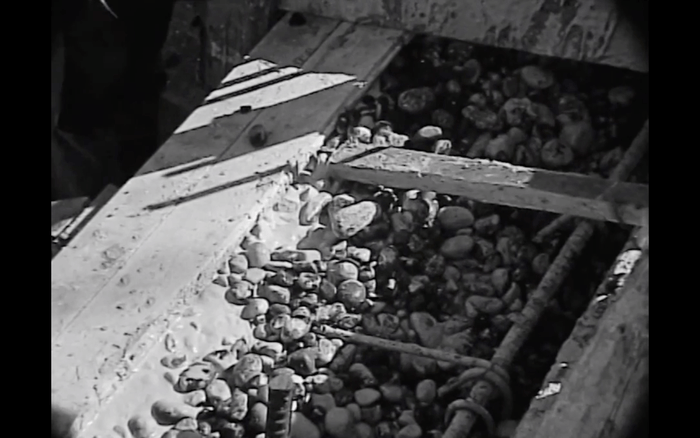

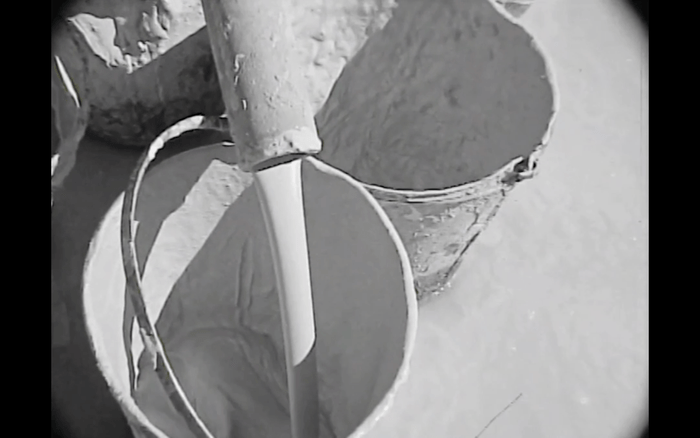

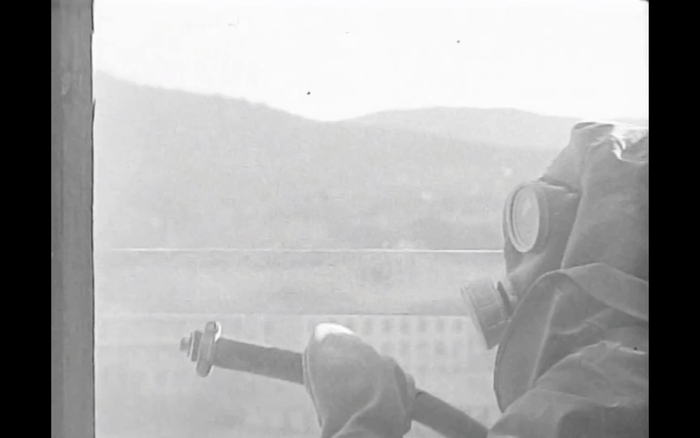

Teigen Fotoatelier. Stills from film “Nesjar.” 1958. DEX FILM 0001. Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/021116584333/nesjar.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Stills from film “Nesjar.” 1958. DEX FILM 0001. Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/021116584333/nesjar.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Stills from film “Nesjar.” 1958. DEX FILM 0001. Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/021116584333/nesjar.

Henriksen & Steen. Empirekvartalet 1949. URN:NBN:no-nb_digifoto_20200512_00058_NB_HS_49_01052. Nasjonalbiblioteket. https://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-nb_digifoto_20200512_00058_NB_HS_49_01052.

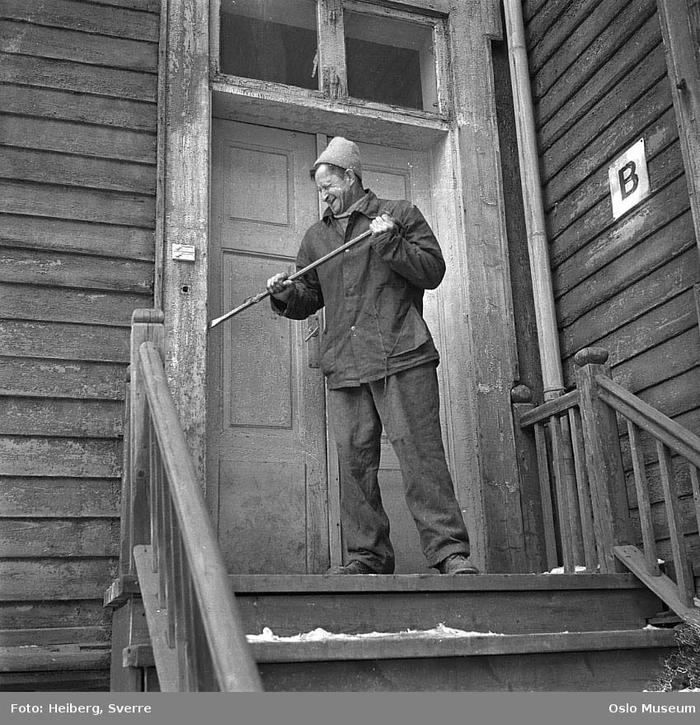

Heiberg, Sverre. Militærhospitalet rives. March 1962. OB.AH17236a. Heiberg, Oslo Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/021018614990/miltaerhospitalet-rives.

Photographer Unknown. Empirekvartalet rives. June 1959. NFDB.26106-156. Dagbladet, Norsk Folkemuseum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/011013618682/empirekvartalet-rives-oslo-juni-1959.

Photographer Unknown. Fra rivingen av Empirekvartalet. June 1954. Oslo Byes Vel. https://oslobyleksikon.no/sideMilit%C3%A6rhospitalet.

Photographer Unknown. Empirekvartalet rives. October 1954. AAB-012102b. Arbeiderbladet. https://digitaltmuseum.no/021016537566/empirekvartalet-rives-oktober-1954.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringsbygget. Photograph. 1958. DEX_T_4420_019. Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/0210111807311/regjeringsbygget.

Unknown Photographer. Akersgata 44. c.1890–1900. Riksantikvaren. https://kulturminnebilder.ra.no/fotoweb/archives/5022-Foto-fri-bruk-(CC-BY)/RA1/RA1/Topnummer/T001_04/T001_04_0904.tif.info#c=%2Ffotoweb%2Farchives%2F5022-Foto-fri-bruk-%28CC-BY%29%2F%3Fq%3Dakersgata%252044.

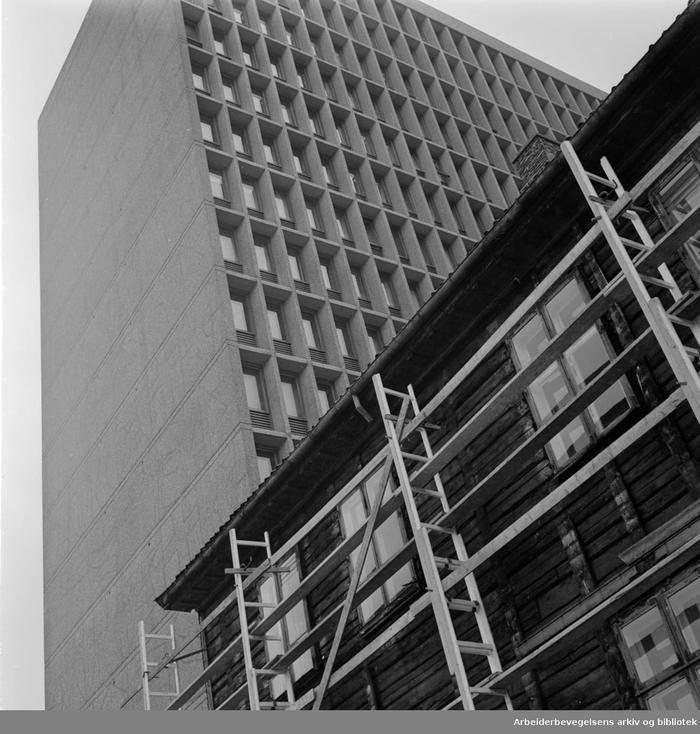

Unknown Photographer. Regjeringsbygget i Rgjeringskvartalet [sic] under oppføring. Photograph. 5 October, 1957. NFDB.26792-819. Dagbladet, Norsk Folkemuseum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/011013628944/regjeringsbygget-i-rgjeringskvartalet-under-oppforing-bygningen-i-forgrunnen.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringsbygget. Photograph. 1958. DEX_T_4420_038. DEXTRA, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/0210111807329/regjeringsbygget.

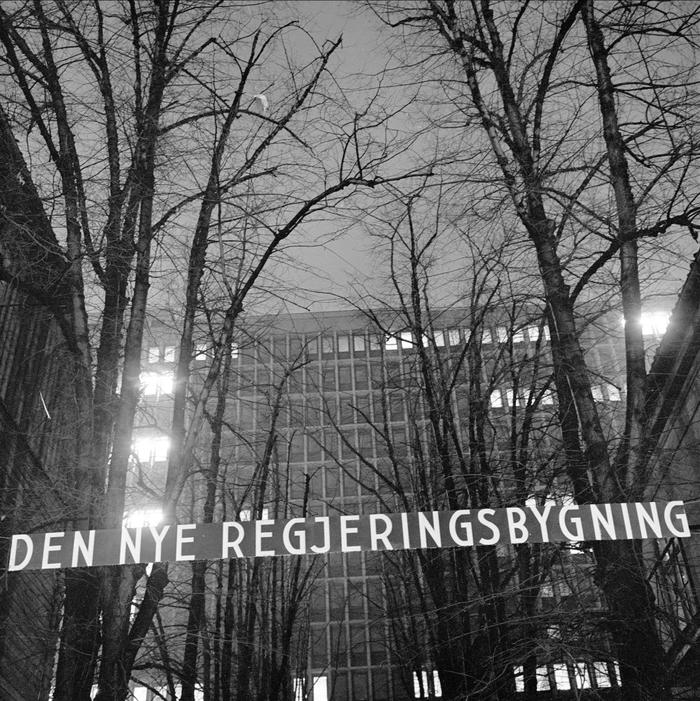

Unknown Photographer. Akersgata, Oslo, 1960. Den nye regjeringsbygningen. Photograph. 1960. NFDB.26792-808. Photography - 1960 (Envelope), Dagbladet, Norsk Folkemuseum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/021018735902/akersgata-oslo-1960-den-nye-regjeringsbygningen.

Heiberg, Sverre. Militærhospitalet demontering. Photograph. 1960. OB.AH0805. Heiberg, Oslo Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/011014318880/militaerhospitalet-demontering.

Unknown Photographer. Empirekvartalet. c.1900—1910. Riksantikvaren. https://kulturminnebilder.ra.no/fotoweb/archives/5022-Foto-fri-bruk-(CC-BY)/RA1/RA1/Topnummer/T001_09/T001_09_2393.tif.info.

Unknown Photographer. Empirekvartalet rives. March 1962. AAB-012103b. Arbeiderbladet. https://digitaltmuseum.no/021016537567/empirekvartalet-rives-akersgt-44-mars-1962.

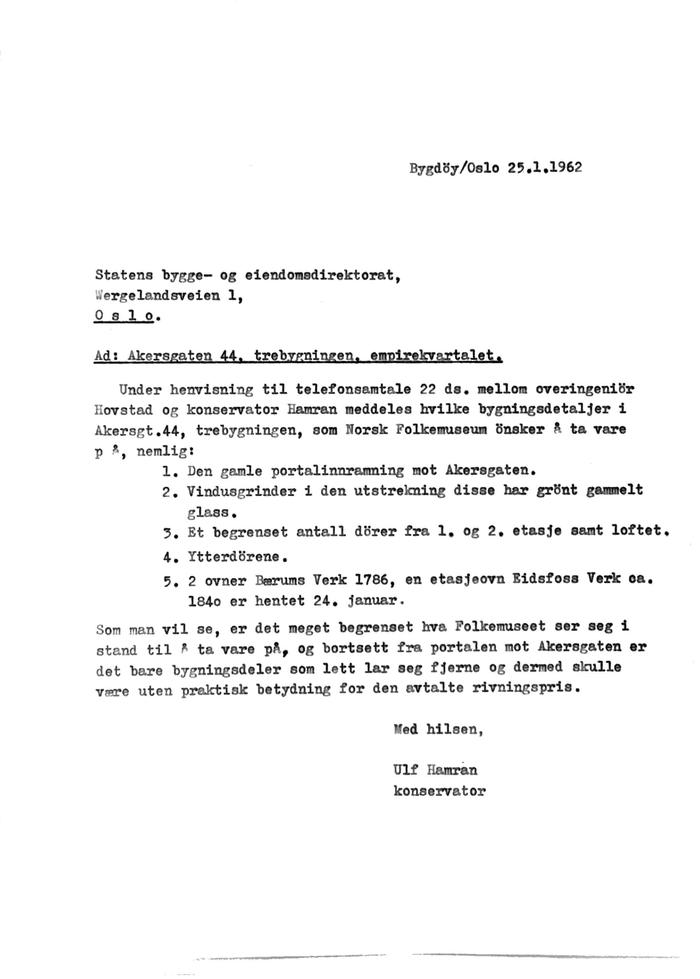

Letter from Conservator Ulf Hamran. 25.01.1962. Norsk Folkemuseum.

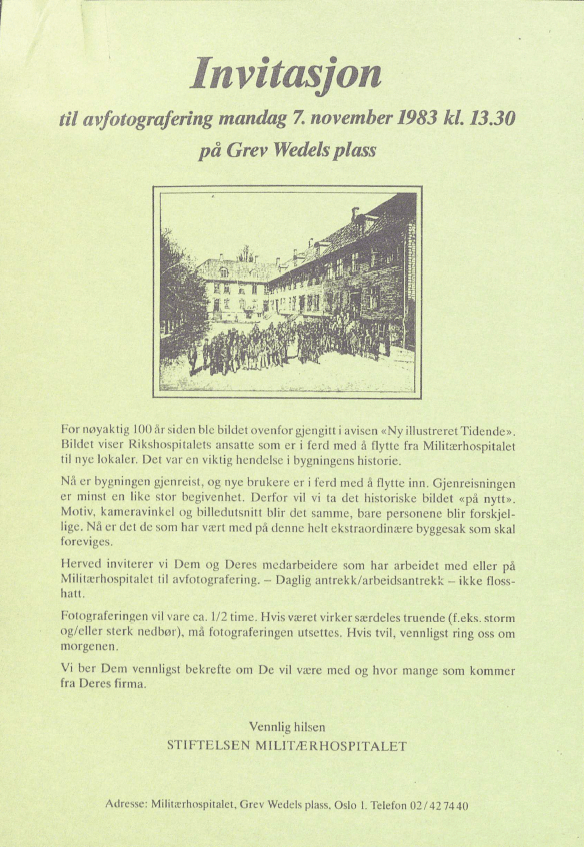

Stiftelsen Militærhospitalet. Invitation to the inauguration of the rebuilding of Militærhospitalet. 07.11.1983. Militærhospitalet Korrespondanse 1983, NMFK_NG-1000_Y_Yb_L0017, Nasjonalgalleriet, Nasjonalmuseum.

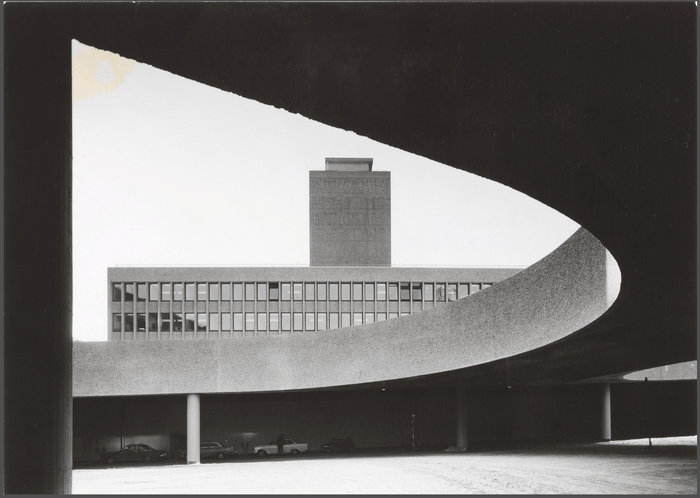

The so-called G-block was designed by Henrik Bull in 1906.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringskvartalet med Møllergt. 19. c. 1988. DEX_T_5585_002. DEXTRA Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/0210111913301/regjeringskvartalet-med-mollergt-19-des-78.

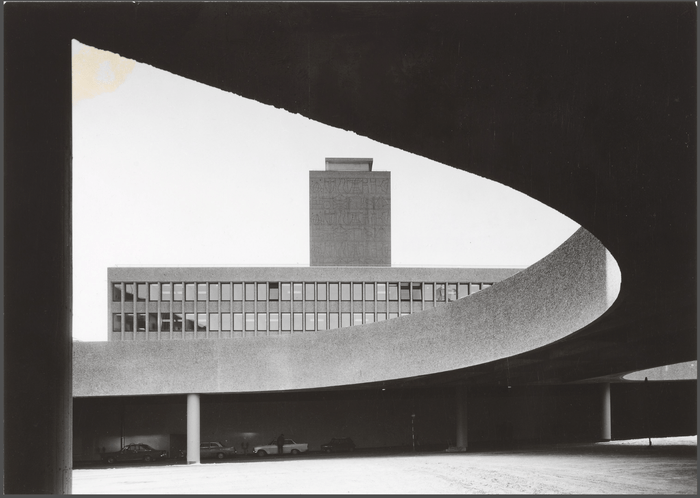

Høyblokka, the H-block, was designed by Erling Viksjø in 1958.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringsbygget. Photograph. 1958. DEX_T_4420_019. Dextra Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/0210111807311/regjeringsbygget.

The S-block, was designed by Viksjøs Arkitektkontor in 1978 and demolished between 2014–15.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringskvartalet. 1978. DEX_T_5585_007. DEXTRA Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/0210111913304/regjeringskvartalet.

Y-blokka [Y-block] was constructed in 1969 and demolished between 2020 and 2021. The building, along with Høyblokka (in background) was designed by architect Erling Viksjø.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Regjeringskvartalet. Photograph. c. 1969. DEX_T_2903_008. DEXTRA Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/011012600276/regjeringskvartalet.

The A-block, was designed by Team Urbis and is currently under construction.

Team Urbis and Nordic Office of Architecture. A-blokken. Statsbygg. https://www.statsbygg.no/prosjekter-og-eiendommer/nytt-regjeringskvartal.

The C-block, was designed by Team Urbis and is currently under construction.

Team Urbis and Nordic Office of Architecture. C-blokken. Statsbygg. https://www.statsbygg.no/prosjekter-og-eiendommer/nytt-regjeringskvartal.

The D-block, was designed by Team Urbis and is currently under construction.

Team Urbis and Nordic Office of Architecture. D-blokken. Statsbygg. https://www.statsbygg.no/prosjekter-og-eiendommer/nytt-regjeringskvartal.

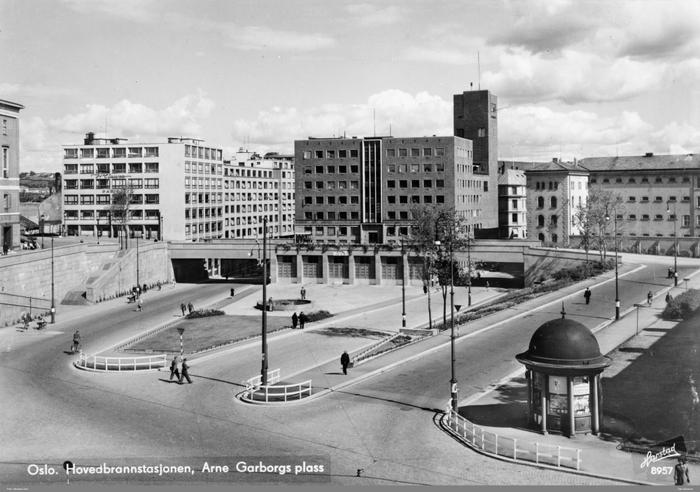

Harstad, Karl. Arne Garborgs plass. c.1945. OB.F04018a. Byhistorisk samling, Oslo Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/021015873512/oslo-hovedbrannstasjonen-arne-garborgs-plass.

Teigen Fotoatelier. Erling Viksjø’s model for Regjeringskvartalet showing Einar Gerhardsens plass in the back. Undated. DEX_T_5585_032. DEXTRA Photo, Norsk Teknisk Museum. https://digitaltmuseum.no/0210111913327/regjeringskvartalet.

Team Urbis and Nordic Office of Architecture. Regjeringskvartalet. Statsbygg. https://www.statsbygg.no/prosjekter-og-eiendommer/nytt-regjeringskvartal.

Manna, Jumana. Substitute. Forthcoming, 2025. Statsbygg.

Written by Alena Beth Rieger (PhD fellow in architectural history, b. 1994) in conversation with Jumana Manna (artist, b. 1987) and Drew Snyder (curator, b. 1985). The essay emerges from two ongoing, independent projects regarding the same location in Oslo, Norway. Akersgata 44 was home to the Empire Quarter [Empirekvartalet] from 1807 to 1954 and the Government Quarter [Regjeringskvartalet] from 1954 to 2020. It is the site of the new Government Quarter, currently under construction. In 2022 artist Jumana Manna was awarded a public art commission for the new development. Her work, Substitute (working title), is curated by Drew Snyder. Alena Beth Rieger writes about demolition and material provenance. She is curious about the perennial demolitions at Akersgata 44 and tracing the paths of the leftovers.

Bewildered by the twenty-four-hour definition of a day, Ali Smith’s adolescent character in her novel The Accidental (2005) attempts to find a day’s beginning by filming each morning over a boring summer in rural England. Her footage captures moments in which night seamlessly transitions into day: birds chirp, winds turn, the town stirs. Our frustrated protagonist wakes up earlier and earlier. Her beginnings stretch further back until they are no longer the start of one day but the end of another. With a similar curiosity this text extends backwards, over starts and stops and overlaps, at one site in the centre of Oslo, Norway.

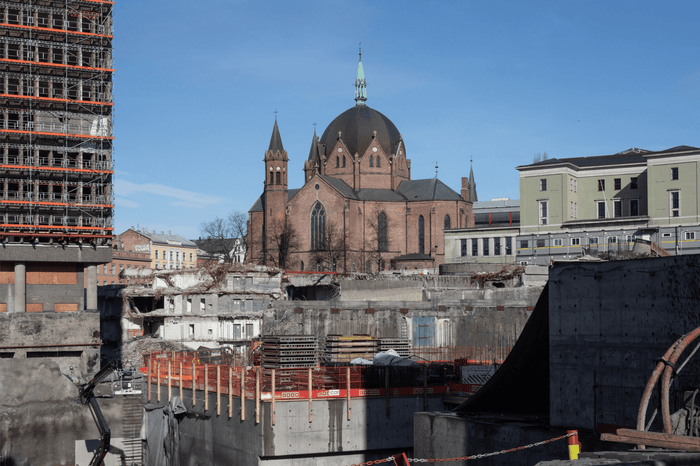

Akersgata 44, part of an area once described as the “Acropolis of Norway,” is today a hole rather than a hill.For the second time in just sixty years, the site is in the midst of a controversial interlude: a familiar fight for preservation, the spectacle of demolition, a start to new construction. Akersgata 44 has often been defined by its development—from the Empire Quarter (1806–1962), named after its neoclassical Empire-style architecture, to the Government Quarter (1954–2020) to the new Government Quarter (under construction)—but building begins with unbuilding. Breaking ground inaugurates the ephemeral, episodic process of construction, and there are many ways to undo architecture. To demolish, destroy, destruct, disappear, raze, flatten, or level a building implies a clearly defined ending, while deconstructing, dismantling, unbuilding, spoliating, subtracting, or displacing suggests an altered continuation. Some of these words imply a complete extinction but we know—just as a building is never truly new, its materials have simply gone through a process of transformation and approval—a building can never fully disappear.

There are many ways to write the architectural history of Akersgata 44. Many have. Some have written on the collective memory of the site after the tragedy of July 22, 2011, when a right-wing extremist set off a fertilizer bomb at the base of the main government building, killing eight people and injuring hundreds (the extremist would later that day kill a further sixty-nine people on the island of Utøya).1 Others have written on the protests against the demolition of those targeted buildings or on the meaning of that inevitable demolition.2 Some have focused on the monumental architecture of the welfare state in the 1960s;3 the classicist architecture it replaced;4 or, with a longer range, on the development of the site through its infrastructural changes.5* What might be learned, then, from a history of Akersgata 44 told in fragments rather than continuities, disjointed rather than smooth? This text stretches backwards, unfolding the history of the site through its physical transformations. And while this material history risks excluding facets of the address, it does so with a conviction that such a place should be written through many prisms, by many.

1 See Mattias Ekman, “Edifices. Architecture and the Spatial Frameworks of Memory” (Arkitektur- og designhøgskolen i Oslo, 2013); Sebastian Jørung Øvrebø, “Byggesak 201912777” (Arkitektur- og designhøgskolen i Oslo, 2022).

2 See Ekman, “Edifices. Architecture and the Spatial Frameworks of Memory”; Tone Hansen and Marit Paasche, eds., Vi lever på en stjerne (Oslo: Henie Onstad Kunstsenter and Forlaget Press, 2014); Øvrebø, “Byggesak 201912777”; Dag Erik Elgin, “Offentlig kunst som formuesobjekt,” Kunstkritikk (2021).

3 See Espen Johnsen, Erling Viksjø (Oslo: Pax forlag, 2020); Hugo Lauritz Jenssen, Høyblokken. En bygningsbiografi (Oslo: Forlaget Press, 2013).

4 See Arno Berg, Empirekvartalet i Oslo, ed. Fortidsminneforeningen (Oslo: Grøndahl & Søns Boktrykkeri, 1949); Harry Fett, Vår hovedstad tar form (Oslo: Gyldendal, 1954).

5 See Braathen, Martin, Marius Engh, and Even Smith Wergeland. “Ekkokammer / Et Samlingssted for Gauker, Halliker, Homoseksuelle Og Andre” in Vi Lever På En Stjerne, edited by Tone Hansen and Marit Paasche, 110–24. Oslo: Henie Onstad Kunstsenter og Forlaget Press, 2014.

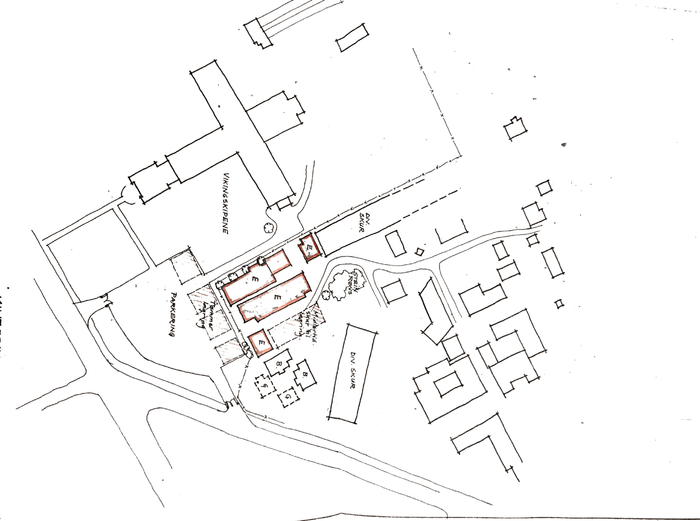

A hole in a stone wall in the municipality of Namsos—a large area north of Trondheim with few inhabitants, once lined by forests and sawmills, and heavily bombed during the Second World War—marks the transfer of a stone from a political periphery of Norway to the centre of it.6 The extracted piece comes out of a lineage of tragedies: from a retaining wall built from a bombed church (1940) constructed after a town fire (1897).7 Today, the stone rests some 500 kilometres from its extraction point, alongside other materials taken from most corners of the country, in a publicly commissioned artwork. Jumana Manna’s Substitute makes use of materials gifted and then extracted from ninety-two locations around Norway—from schools, churches, pavements, power stations, and bridges. The fragments are assembled as an 800-square-meter floor in the centre of the new Government Quarter, on the exact site of Y-blokka (Government Quarter, demolished 2020), and Militærhospitalet (Empire Quarter, deconstructed 1954–62) before that. On a site which has historically been characterized by the dissemination of policies and materials, Manna accumulates.

Three new buildings with meeting areas, bathrooms, and Zoom rooms for 2500 employees have already been built at the new Government Quarter. Each day, as trucks relocate desks, chairs, and computers that will service Norway’s government employees, they roll over an undulating surface of stone—a “tulip pattern” of notched, angular, black-and-white figures.8 The carpet of city floor is a swollen, flattened reference to architect Erling Viksjø’s motif for the columns of Høyblokka, described by its architects Team Urbis as “lasting, dignified, beautiful and friendly.”9 It has been proposed that Viksjø’s original pattern was inspired by rosemaling, the Norwegian folk art of painting domestic wooden surfaces with floral patterns of iron-based reds, quartz whites, cobalt blues, and ochre yellows.10 In the wake of the 2011 terror attack and in the midst of tumultuous conversations on the future of Akersgata 44, Manna cast Jesmonite copies of Viksjø’s columns in the ground floor of Høyblokka.11 The tulip pattern then made its way, via Manna’s artwork “Government Quarter Study” (2014), to the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter outside of Oslo and the Venice Biennale.12 As the pattern returns to the public floor of the new Government Quarter, it records a translation from stone (pigments), to wood (surfaces), to concrete (columns), to Jesmonite (copies), and back to stone again (floor).

Manna’s new work, Substitute, interrupts this gridded, abstracted repetition of tulips with the spoliated stones from around the country. Cobbled pieces—green, yellow, brown, grey, and red, angular, triangular, curved, broken, industrially cut, and weather worn, made of marble, limestone, cobalt, iron ore, granite, gneiss, quartz, larvikite, a piece of concrete, and a carved stone owl—break with the newness of the new quarter. In a site which has been exhaustively imagined before it is finished, Substitute is a fusion of out-of-place references and materials.

Out-of-place elements have a long history in new construction. By the beginning of the fourth century, the use of spolia was gaining popularity; columns and capitals of various origins were being visibly placed on new, prominent structures in the Roman Empire.13 On-site workshops producing purpose-built components were soon phased out by disassembled building components stockpiled in city storages.14 As Maria Fabricius Hansen explains in The Eloquence of Appropriation (2003), these elements were “products of a more prosperous past.”15 They carried with them more meaning than material. What kind of spolia are the stones in Substitute, then? Not taken under duress. Not signifiers of a violent conquest. With considerable agency in the hands of donors. In municipalities which gifted pieces of stone for use in the artwork, the question of representation became a topic of considerable local interest. Headlines in newspapers asked readers to consider what history represented them, what stories they would tell. When the collection of reused stones appears in the floor of the new quarter, they reverse the direction of influence between centre and periphery. Using the material histories of the spolia, Manna brings provincial provenances to the capital.16

6 The municipality has around 15,000 inhabitants.

7 Tor Martin Årseth, “Her fjernes en stein fra muren i Vika—skal sendes sørover. En viktig del av byhistorien,” Namdalsavisa, September 1, 2023.

8 Espen Johnsen, Erling Viksjø: Eksperimenter i form og betong (Oslo: Pax forlag, 2020), 207.

9 The original text reads: “varig, verdig, vakkert og vennlig”; KORO, “Kunstplan Del 1: Kunst I Nytt Regjeringskvartal,” (2021), 7, 43.

10 Johnsen, Erling Viksjø: Eksperimenter i form og betong, 207.

11 Jesmonite is a plaster-like material made of gypsum and resin.

12 The work was included in the exhibition Vi lever på en stjerne, Henie Onstad (2014), and in the Nordic Pavilion at the 57th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia (2017).

13 Maria Fabricius Hansen, The Eloquence of Appropriation: Prolegomena to Understanding of Spolia in Early Christian Rome, Analecta Romana Instituti Danici (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2003), 7–20.

14 Ibid., 7–13, 17.

15 Ibid., 7

16 Decisions on topics as broad as housing, language, and healthcare have historically been taken centrally and distributed nationally.

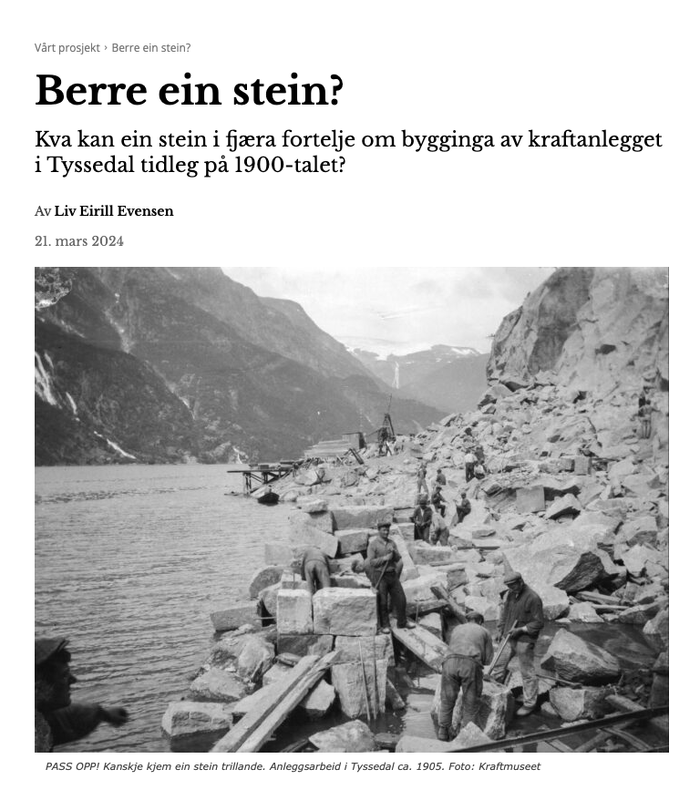

Substitute began with an invitation (a sketch, a description, and a request for contributions) sent to the emails of all 357 municipalities in Norway. Responses came quickly from those with stone architecture to offer, in the process of renovations, and with interest in the project. Local newspapers expressed similar enthusiasms: “Stone from Høyanger becomes art in Oslo”; “Asker-stone will appear in the new Government Quarter”; and excitement from Tyssedal that a stone which “built Norway” will “go on an adventure” to the new quarter.17

For six months in a barn in Lier—an agricultural area some forty kilometers by car from Akersgata 44, famous for its strawberries and apples—laid piles of stones from around the country. From bridges, canals, churches, cloisters, and dams; factories, fences, footpaths, fortresses, fountains, monuments, parks, and power plants; quarries, roads, railroads, schools, sculptures, squares, tunnels, and wharfs; from 92 municipalities, a house, and one worker. No matter its original location, size, or material, each stone was delivered to a warehouse in Østfold to be cut to an equal depth of twelve centimeters, shipped to the barn in Lier to be assembled and then disassembled, marked with its provenance, destination, weight, and size, and then packed, moved to Akersgata, and reinstalled. Substitute was rehearsed by Manna, curator Drew Snyder, and a team of craftspeople as they cobbled parts into a whole in that barn in Lier. The composition grew out of a corner as fragments came off the truck. No legible patterns—nor maps, themes, or tones—were used to create the work. What was gifted was used.

Material guidelines were set early in the process. Each piece was to be: (1) reused, (2) publicly owned, (3) stone, (4) from within Norway. Though the brief stipulated that the artwork be made of Norwegian stone, Manna construed this to include any stone currently in Norway, not only extracted from its bedrock, meaning that today, there is Indian stone, Chinese stone, Portuguese stone, and Swedish stone cemented into the ground of the new Norwegian Government Quarter. From “from” to “in,” the shift in preposition evokes Hans Haacke’s (b. 1936) amendment from “people” to “population” in his work DER BEVÖLKERUNG (To the Population), a piece consisting of donated deposits of soil from 449 areas around Germany set into a frame containing the words “DER BEVÖLKERUNG” [to the population], laid on the floor of the Reichstag in Berlin. The enlarged script referenced a salutation once placed on the adjacent building, “DEM DEUTSCHEN VOLKE” [to the German People]. Haacke dwelled on this shift in meaning, from “the people” to “the population”, addressing those in a place instead of those from it, just as Manna subtly shifts to using materials in Norway instead of materials from it.

Substitute also reflects a longstanding tradition of employing material histories at Akersgata 44. Still, the history of extraction and expulsion is complex, even mythological. Erling Viksjø‘s aggregate for the Government Quarter buildings came from a river in Hønefoss and ended up as landfill in Sørum when Y-blokka was razed. The timber used for the wooden Empire Quarter building came from Gudbrandsdalen, was stored for decades at Norsk Folkemuseum, and is now reconstructed near the harbour of Oslo. For its part, Substitute represents some of the communities and dynamics that constitute Norway. But many are absent. Few stones represent migrant or minority communities, many of whom lack buildings and other infrastructure to call their own. Other regions simply have no history of building in stone. Manna says it most clearly: “the overall composition speaks to the absence of specific structures that do not represent, for example, the Pakistani community or the Kven community or the queer community.”18 As a work, Substitute is not only the accumulated pieces in the floor of the new Government Quarter. It is the holes left around the country and the connection made between disparate places.

17 Stig Hovlandsdal Øvreås, “Stein frå Høyanger blir kunst i Oslo,” Ytre Sogn, May 26, 2023, 1; Elin Reffhaug Craig, “Asker-stein vil synes i nytt regjeringskvartal,” Budstikka, June 5, 2023, 8; Liv Eirill Evensen, “Berre ein stein?,” Tidsskriftet museum, March 21, 2024.

18 Discussion with Jumana Manna and Drew Snyder. June 14, 2024. 00:55:00.

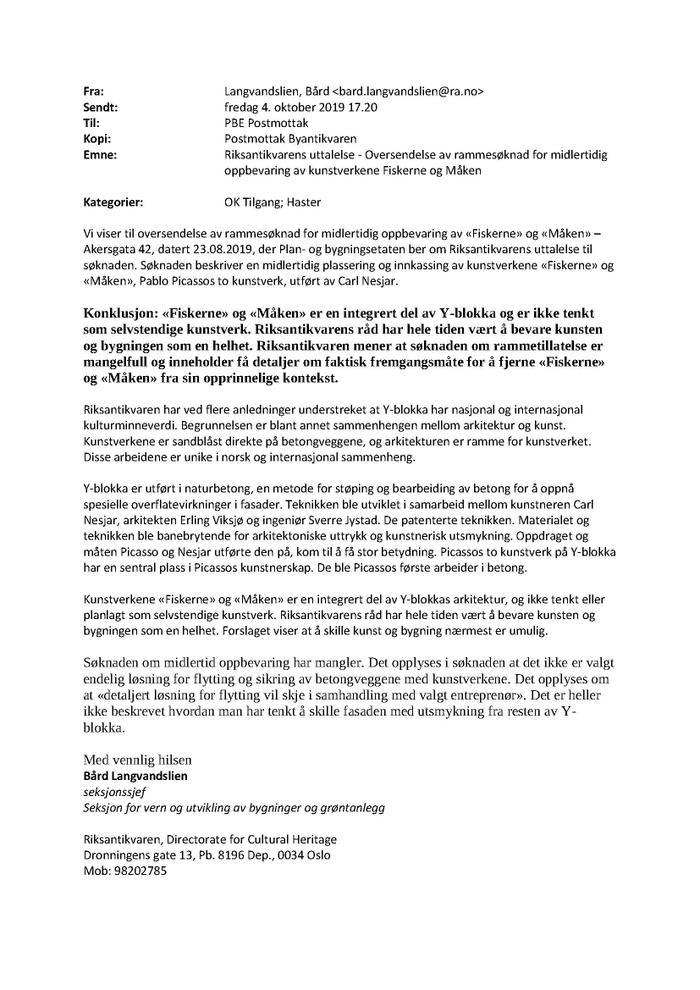

During forty-five minutes of 2020, a crowd watched as the southern gable wall of Y-blokka was dislodged, moved fifty meters, and encased in a climate-controlled box.19 This entire wall, with an approximate length of fifteen meters and height of eleven, was officially defined as a work of art.20 The classification was the result of a sandblasted concrete relief, co-authored by artists Carl Nesjar and Pablo Picasso. Y-blokka, the low-slung block, and Høyblokka, a sixteen-floor tower, once constituted a central part of Oslo’s Government Quarter. The modernist buildings were designed by architect Erling Viksjø and constructed, mid-century, at the expense of the so-called Empire Quarter, including Militærhospitalet, which preceded it. The dark aggregate of Y-blokka’s walls formed a frame around the lighter, cemented work of Picasso. The relief and its notable authors were cited in every argument for preservation of the building. As one section leader at Riksantikvaren [the Directorate for Cultural Heritage] remarked, “separating the art from the building is close to impossible.”21

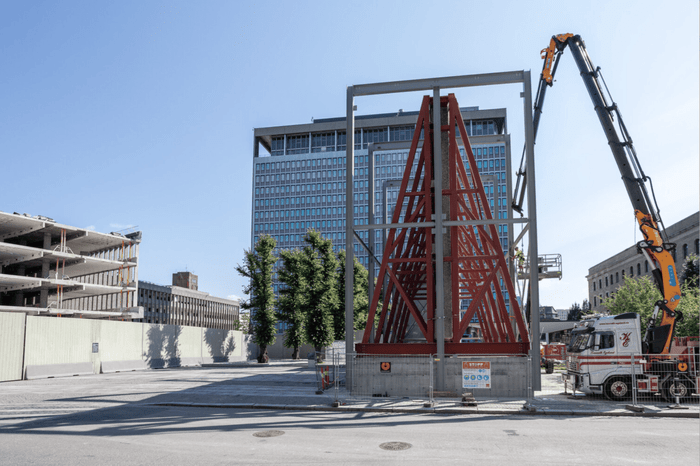

The separation of art from building went something like this: any architecture below the artwork was removed and replaced by a 140-tonne steel frame; the gable wall was sawn from the building in reverse order—first through the parapet, fifth floor, fourth floor, third floor, second floor; the weight of the 250 tonne wall was transferred to the steel frame; the frame was driven 50 meters to the south and parked atop concrete foundations before a climate-controlled box was built around it. This box, the frame, and the gable wall were estimated to rest here for five to ten years, but were already disassembled by the winter of 2024.22 During this period, the remaining building was razed, the site levelled, the new one constructed, and the gable wall re-placed in its new quarters. Through its lingering presence on-site, the extracted wall spanned the destruction of Y-blokka and the ongoing construction of its replacement.

At the same time as architects were competing to reimagine the site on their terms, committees were drawn up to manage the displacement of historical works and the commissioning of new ones. The physically and socially divisive task of spoliating Picasso and Nesjar’s integrated relief, Fiskerne (1968), fell under the jurisdiction of KORO [Public Art Norway], the “national body responsible for curating, producing and activating art in public space,” the same organization which commissioned Manna’s Substitute, and is in the midst of commissioning several new artworks for the new Government Quarter.23 Along with Fiskerne comes existing works from artists Do Ho Suh, Inger Sitter, Hannah Ryggen, Kai Fjell, Odd Tandberg, and Tore Haaland. In documents describing the process, KORO speculated on the relationship between the commissioned and retained works in the quarter, writing that “while new works are important additions to the existing ones, they also contribute to readings of—and stories about—the historical works.”24 Like Hannah Ryggen’s flat tapestry, Vi lever på en stjerne (1958), and Picasso and Viksjø’s Fiskerne (1968), Substitute compresses varied materials into a shallow irregular surface purpose-made for the site it sits in. But for Manna, collecting the materials through this open-call process meant allowing “unexpected elements to enter and change the composition” to contribute “a dynamicism that wouldn’t be possible if everything was predetermined.”

“The architecture is the frame for the artwork” wrote the section leader at Riksantikvaren in his appeal for preservation of Y-blokka.25 But once the most valuable piece of Y-blokka had been removed, the remaining building shifted from frame to background. Both Y-blokka and Høyblokka had been on the minds of preservationists in the 2000s who, by 2011, were closing in on protected status for the buildings.26 On July 22, 2011, terror struck. The brutal attack left a country in mourning. It was soon reported that both buildings were structurally intact, but the need for repair and increased security forced a reconsideration of the proposed heritage status. At the same time, the buildings’ resilience against the attack proved meaningful for a large public. In 2014, the government, led by the conservative party Høyre, announced that Y-blokka would be demolished—the public tunnel that ran below it formed too great a security risk. Protests began immediately. The events sparked an international preservation campaign aimed at the monumental buildings and the integrated artworks they contained. A series of banners protesting the demolition would soon read: “undamaged by terror, demolished by the government.”

The dissenting public was adamant: the demolition was “against all common sense,” “undemocratic,” “tragic,” “a dramatic loss,” and only comparable “to the demolition of our last stave churches.”27 Protests led to several pauses, but the attempt at preservation failed to conserve the building in its entirety. By August 2020, the safe extraction of valuables set in motion the demolition of the remaining building. Protesters resigned, demolition advanced. From August 2020 to February 2021, a steel claw grabbed at the building until it resembled the pile of rocks it was constructed from.

19 Teknisk Ukeblad, “Nå fjernes Picasso-kunsten fra Y-blokka,” streamed live on July 30, 2020, YouTube, 3:11:25, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHNHgruyUsA&t=1014s&ab_channel=TekniskUkeblad.

20 Team Urbis, “Alternativer for midlertidig plassering av ‘Fiskerne’ og ‘Måken’,” in Søknad om rammetillatelse (Saksinnsyn, December 20, 2018), 2.

21 The move and debate around it was beautifully discussed in Sebastian Jørung Øvrebø’s Master’s thesis in architecture, “BYGGESAK 201912777: The Picasso Boxes.” I have primarily traced the move and demolition of Y-blokka through demolition documents available on Saksinnsyn, but details, such as Langvandslien’s letter, were first brought to my attention by Øvrebø. This section also owes a debt to Dag Erik Elgin’s article “Offentlig kunst som formuesobjekt” in Kunstkritikk. The original text reads: “å skille kunst og bygning nærmest er umulig.” Bård Langvandslien, “Riksantikvarens uttalelse – oversendelse av rammesøknad for midlertidig oppbevaring av kunstverkene Fiskerne og Måken,” (Saksinnsyn, October 9, 2019), 1.

22 Urbis, “Alternativer for midlertidig plassering av ‘Fiskerne’ og ‘Måken’,” 10–11, 14.

23 KORO, “What Is Koro.”

24 “Kunstplan Versjon 2,” (2023), 7.

25 The original text reads: “Kunstverkene er sandblåst direkte på betongveggene, og arkitekturen er ramme for kunstverket.” Langvandslien, “Riksantikvarens uttalelse – oversendelse av rammesøknad for midlertidig oppbevaring av kunstverkene Fiskerne og Måken,” 1.

26 Janne Wilberg and Morten Stige, “Byantikvarens uttalelse,” (Saksinnsyn, January 25, 2019), 1.

27 Espen Viksjø, “Riving av Y-Blokka – innspill,” (Saksinnsyn, March 17, 2019); Wilberg and Stige, “Byantikvarens uttalelse,” 3.

On February 17, 2020, a certificate of completion finds that Y-blokka has concluded. Its remains are all properly disposed of and accounted for. One November morning, at just one disposal site, semi-trucks each carrying around thirty tonnes of contaminated concrete arrived at 08:22, 08:25, and 08:27 a.m. Deliveries of this size and frequency continued until the evening, and then repeated at a similar pace for seventeen days afterwards. 892 truckloads, or nearly 20,000 tonnes, of crushed Y-blokka were delivered. The mass of material which once contained artworks by notable figures and housed important government functions will be used as landfill for 1300 meters of new road in Sørum municipality. Pedestrians, vehicles, and cyclists will enjoy a lit, rural road built upon the crushed stone of Y-blokka.

Not everything from the demolition was trash to be disposed of. Three well-built dining tables and their fifteen accompanying chairs were moved into the construction site office. A nearby karate club claimed 100 square meters of ceiling panels, twelve lights, and two wardrobes. A helicopter platform from the neighbouring building is still for sale online. A spreadsheet, labelled K-12 Recycling List, describes the decomposition of the building in unsentimental terms. The “Picasso art” sits mid-page, between four containers of plants (which are given to a nearby farm) and teak window frames (which cannot be reused because they turn out to be laminated chipboard, containing PCBs). According to the spreadsheet, many pieces which survived the terror attack—wall lamps, doors, window frames, a telephone—have been reused in the commemorative 22 July Centre. In this flooded taxonomy, some perennials and a few nearly-teak window frames appear equal to the large helicopter pad, or Picasso’s art. Apart from the gable wall, nothing from this list appears in the renderings of the new quarter, which depict buildings adorned with suits, children, blue sky, and art. The Picasso-Nesjar frieze sits off-centre, off-the-ground, and out-of-place in the new square.

The gleaning of particulars during destruction recalls the building’s construction, when five million stones were extracted from a river in Hønefoss and accumulated as concrete aggregate in Y-blokka.28 The stones were revealed on the facades of the building through a technique patented by Viksjø and engineer Sverre Jystad in 1957. Patent 90310 describes the new “procedure for pouring concrete.” Naturbetong [natural concrete], as it was later called, involved filling a mould with coarse aggregate, pressing cement mortar between the stones, and then sandblasting the exterior of the formed concrete wall.29 In 2020, the stones once shaped by river currents, constructive formwork, and Nesjar’s sandblaster were once again loosened during demolition—this time by excavators and saw blades.30 Today, just one of the Government Quarter’s buildings is left standing. Høyblokka and Y-blokka once formed an inseparable pair. In its singularity, Høyblokka has absorbed the turbulent history of the Government Quarter, including the terrorist attack of 2011, the controversial redevelopment of the site, and the quarter it replaced six decades before.

28 Odd Hølaas, “Den nye regjeringsbygningen – et nytt materialinnslag i europeisk arkitektur,” Dagbladet, December 21, 1957.

29 Sverre Jystad and Erling Viksjø, Fremgangsmåte ved betongstøpning, Norway Patent 90310. Approved September 7, 1957.

30 Picasso and Nesjar—as well as Inger Sitter, Tore Haaland, and Odd Tandberg—all created integrated artworks using naturbetong in the quarter.

The demolition of the Empire Quarter began with a crowbar to its north-western staircase in October 1954. By the end of the year, two brick buildings and 8 meters of the wooden Militærhospitalet had disappeared, foundations for Høyblokka had been dug, and concrete was pouring in. Over the next eight years, an “architectural circus” took place as the construction of the modernist Government Quarter necessitated the destruction of the Empire Quarter.31 The condemned Militærhospitalet remained in place and was employed as a site office during the interlude of the two projects. This phased demolition of the Empire Quarter and the staggered inauguration of its replacement caused some of Norway’s most iconic buildings to be temporarily interdependent. The simultaneity of demolition and construction were further complicated by site visits from antiquarians, protestors, wreckers, contractors, potential buyers, and the tenants of the new building—including the Norwegian prime minister.

Contractors might have preferred a working plane with more space and fewer obstacles, but Akersgata 44 was squeezed in every direction. Public roads restricted the site on each edge, the perimeter of the plot still contained buildings of the Empire Quarter, an old allé of trees to be preserved stood at its centre, and a long-running kiosk occupied the northern corner of the site, selling newspapers with daily headlines about its progress. One of these headlines remarked that Militærhospitalet and the newly-completed Høyblokka now stood like “a little David” and a towering “Goliath.”32 The puzzling duo captured the public’s attention and produced an abundance of documentation. Photographs of Akersgata 44 in this interlude celebrate the dawn of the new Government Quarter, but the old Empire Quarter appears difficult to frame out. One image shows a banner suspended from two Empire Quarter buildings which flank Høyblokka. “THE NEW GOVERNMENT BUILDING” is here, the sign proclaims. The images celebrating the new quarter are the swan song of the former. Over several months in 1962, crowds watched as one of Norway’s largest wooden buildings was carefully disassembled and transported off-site.

Militærhospitalet was once monumental. Completed in 1807, the building had a history of notable tenants: a name-giving, purpose-built military hospital, the country’s first national hospital, and numerous public offices. Despite its prominence, the building had been on its way out since development plans for the site assumed its demolition already in the 1890s. When the new Government Quarter materialized over half a century later, the Empire Quarter was finally demolished. A large cast protested, including: Oslo Byes Vel, an antiquarian society founded in 1811; Sofie Helene Wigert, the wealthy shipowner who fought relentlessly for the preservation of the Empire Quarter and saved Militærhospitalet by purchasing its materials just days before it was demolished; Leif Torp, founder and architect of the prominent firm Torp & Torp, who, at the age of eighty-six, would design the reconstruction of Militærhospitalet; Johannes Elgvin, the professor who, along with Wigert and Torp, formed the Empire Committee and whose personal archive contains the thirty-year saga; and Reidar Kjellberg, the Norsk Folkemuseum director who first supported and later sabotaged plans to rebuild Militærhospitalet on museum property.

31 “Arkitektonisk sirkus midt i byen,” Dagbladet, February 10, 1962.

32 “Påstand om lovbrudd,” Morgenbladet, March 13, 1962.

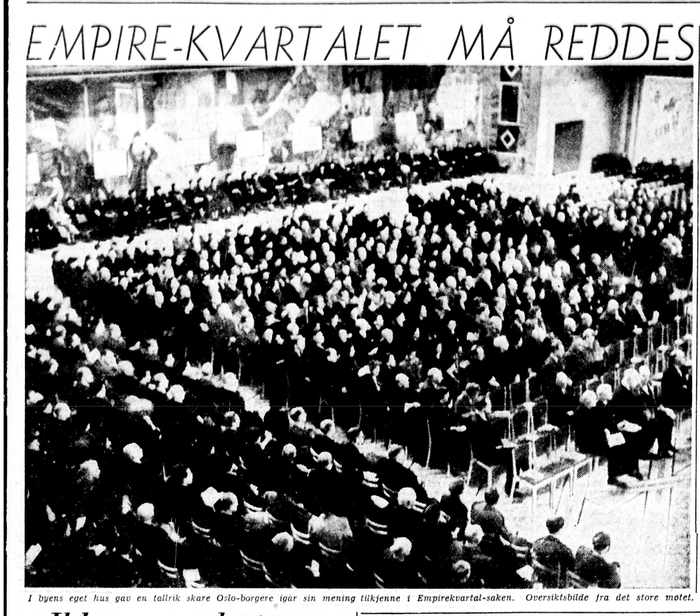

Already in March 1962, though Militærhospitalet had not moved an inch, it was detached from its context. Three out of four Empire Quarter buildings had disappeared, the building’s long wing had been subtracted, and a new high-rise towered above it. Yet according to news reports of the time, Militærhospitalet absorbed its context. As the Empire Quarter was progressively replaced by the Government Quarter, Militærhospitalet became the sole representative of the former site. During this period, newspaper headlines often referred to the building as the “Empire Building” instead of Militærhospitalet. Debates still circled around “saving the Empire Quarter!” And when the discussion was relegated to preserving pieces of the building, they were referred to as the “Empire materials.”33 This was done, perhaps, in the hopes of injecting value or fortifying the argument against dissolution. The Empire Quarter had been on the chopping block since the 1890s and petitions to save it had not produced results. Over 1000 protesters inside Oslo City Hall in January 1953 did little to affect change, but the possibility of detaching the building from its site finally did.34

The fate of Militærhospitalet had been a controversial subject for nearly eighty years, but the debate intensified over one month in 1962 when the building was meant to be razed, its demolition delayed, and the materials sold and resold (and resold again). March 1962 culminated in a surprising reversal—Militærhospitalet would instead be dismantled, displaced, and stored until an envisioned reappearance. Within this short period of time, the ending of the building shifted from a brutal destruction to a careful deconstruction. A rapid increase in press coverage captures the criticality of this moment. Speculation on the building’s potential ranged from firewood to cabin materials, from housing at Norsk Folkemuseum to its reconstruction as a spa in Germany. One newspaper stated that Militærhospitalet, which was now over 150 years old, was entering “a new era of glory.”35

Even when Militærhospitalet was slated for complete demolition, parts were to be stripped from the building and stored in collections. Just weeks before demolition, Norsk Folkemuseum asked that the building’s most valuable pieces—the ornamented main portal, green stained-glass mullions, inner and outer doors, and two ovens dating from 1786—be removed and transferred to their architecture collection.36 The architecture department at the museum contained spolia from demolished buildings dating back to the 17th century. Columns, frames, handles, and knobs from disappeared Oslo architecture laid dormant in the inaccessible storage.37 It was precisely this collection of objects for which, in 1959, Director Kjellberg wanted to secure a permanent exhibition space. The soon to be demolished Militærhospitalet emerged as a prudent option. The monumental and vulnerable building shared a common history with the fragments it would hold. Rather than spoliating Militærhospitalet, Militærhospitalet would house a collection of spolia.

The plan to reprogram Militærhospitalet with a collection of spolia never materialized. Nor did the plans to move the building to Germany, rebuild it as cabins in Norway, maintain the building on-site, or construct it as housing at Norsk Folkemuseum. By reducing the building to its material parts it was able to be saved, but reconstituting it proved another fight by other means. In reality, Militærhospitalet was stored at the museum for twenty years while debates around its future moved from the public newspapers to private communication. By 1975, prioritized parking spots and a gas station forced it from the museum’s plans. By 1984, Militærhospitalet was re-inaugurated exactly 1 km from Akersgata 44. Despite the dramatic interlude, the building has been largely forgotten since its resolution in 1984.

33 For example: “Sofie Helene med nytt tilbud i dag,” Romerikes Blad, March 14, 1962, 3.

34 “Empirekvartalet må reddes,” Aftenposten, January 17, 1953.

35 “Empire-kvartalet som kursted i Tyskland?,” VG, March 14, 1962, 1.

36 “To empire-bygninger kan reddes for 1,3 millioner kr.,” Morgenposten, January 7, 1959, 5.

37 Ibid.

A reprinted black-and-white photograph from 1980 shows a man pointing to his right. He gestures in the way a weatherman points at a green screen, or tourists “push” at the Leaning Tower of Pisa. In this background, the deconstructed Militærhospitalet sits in storage—horizontal stacks of windows, vertical piles of logs, more-decorative doors wedged between less-valuable ones, lighter planks placed on top of heavier logs, and everything contained below corrugated steel roofing. The headline of the newspaper article in which the photo is printed contrasts the image of a building in storage with the extravagant price it will cost to reconstruct it, but the tone of the article itself is definitively jubilant.38 It is 1980, and in the eighteen years since these building parts were hastily stacked, Norway has discovered, extracted, and profited from oil in the North Sea. Money is flowing in a way it never has before. The construction industry is booming. Seventeen million kroner for a nationally important rebuilding is hardly a hurdle.39

An ink drawing describes the sort-and-transport operation of 1982 where logs, doors, windows, and frames are to be extracted from this site and accumulated at another. The stacked building of approximately 840 square meters will again expand to 3425 square meters of usable floor space.40

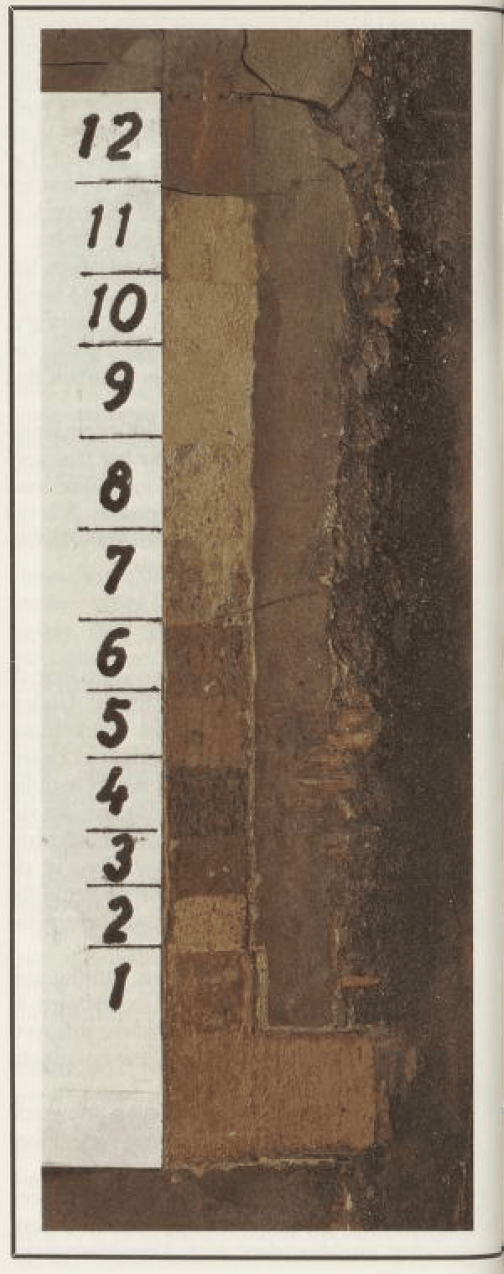

New historical facts came to light during the 1980s reconstruction. Some were arbitrary: the building panels had been repainted twelve times in various shades of yellow-brown.41 Some were more valuable: every log contained two sets of markings, implying two different deconstructions. One set of marks dated from the recent 1954–1962 dismantling, but the other dated back to the original period of construction in 1807. The 1980s reconstruction of Militærhospitalet, which was thought to be the “first time a building this large had ever been reconstructed,”42 was, quite possibly, in its third construction.

In 1806, 1600 timber logs from a state-owned forest and a number of master carpenters made their way from Gudbrandsdalen to Oslo. The 300 km journey ensured the quality of the materials and the expertise of the labourers who would construct them. Each log measured eight to ten meters in length and would withstand an early test construction and deconstruction in the valley from which they were harvested, the transport to Oslo, construction at Akersgata 44, nearly 150 years of use, deconstruction, another move, twenty years of storage, one last move, and this final reconstruction. By the 1984 inauguration, each log rested in its original position at a third location.43

38 “17 mill. for å gjenreise Empirekvartalet,” Aftenposten, 27 May 1980.

39 The construction ended up costing 29.8 million kroner in total. Oslo Byes Vel, “Bygningsfakta,” St. Hallvard, no. 1/84 (1984): 95.

40 Ibid.

41 The original paint colour would be applied during reconstruction.

42 Vel, “Bygningsfakta,” 11.

43 The third location of Mil is near the harbour of Oslo, on the east side of Grev Wedels Plass.

120 construction cases ordered in reverse chronology in the Oslo planning department’s archives detail the many extractions, accumulations, and expulsions at Akersgata 44.44 Today, Y-blokka has been spoliated and Militærhospitalet reassembled elsewhere. The fragments of Substitute are set into the floor. Akersgata 44 is nearing completion. To a site with an existing G-block, H-block, and demolished S- and Y-blocks, have been added A-block, C-block, and D-block. To a removed Arne Garborg’s plass were added Einar Gerhardsens plass and Johan Nygaardsvolds plass. To an existing collection of artworks by Pablo Picasso, Inger Sitter, and Hannah Ryggen are added works by Jumana Manna and others still to be confirmed. Through the process of development, integrated buildings have become distributed parts, demolition has seamlessly transitioned into construction, and extractions, accumulations, and expulsions have repeated, ad infinitum. As Akersgata 44 develops, this text looks backward to detail its history of leftovers—challenging beginnings and endings as explicit moments, looking at spolia which span the gap between destruction and construction, and testing how histories of disappearance might also be stories of endurance.

There are many ways to write about undoing architecture, but architectural history tends to be written between an object’s beginning and end, from beginning to end. When inverting and writing in reverse, what happened comes first, what was intended comes last. We see public reactions and reflections before we hear the intended outcomes. We see ownership before authorship. Maintenance before construction. Repair before disrepair. Old before new. We see demolition and expulsion before construction and accumulation. We see buildings as bottlenecks in the lifespan of their materials.

44 Inclusive of the addresses Akersgata 40, 42, 44.

Alena Beth Rieger , “Extract, Accumulate, Expel (repeat),” Metode (2025), vol. 3 ‘Currents’

Alena’s essay showcases how nothing can be left “untouched” for long, making the reader think about the need of preservation and the dangers of ever-ongoing progress, and how materials hold within themselves so many geographical histories, that are worth to reflect on. I get excited when Alena “lists” things, like building materials, or goes into extreme detail about the specific site where a building was taken apart, etc. She zooms in and out in a very convincing way.

- Martin White

The information is massive, and yet you manage to tell the different stories in a way that makes it possible for to follow. Your essay brings out something valuable about how we relate to our surroundings across a time dimension, how we care, protest, adapt to buildings, material, history, political apparatuses, and not a least how the materials that often are taken for granted and regarded as either stabile and locked in a sense, is exposed in the texts are fluid, flexible, dynamic, they do something. The way you challenge the format, and storyline, is for me a huge part of what Metode is all about.

- Gyrid Øyen

How about we ask our web designer Trond to add small boxes that can include images and captions? These could become visible when the mouse hovers over a hyperlinked word or term. This approach would help create a visually appealing layout that complements the quite complex layers in the written text

- Ingrid Halland