An infill project claims its place; not in defiance but with a shameless appeal: ‘love me more than you do the rest!’

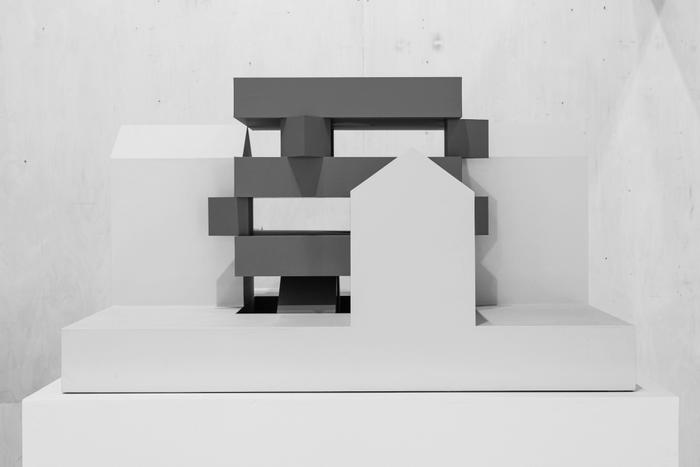

Sandwiched between three buildings in a dense inner city lies a house. Or sandwiched is perhaps the wrong word. Rather as if the house was dropped by an airship from a height of 2,000 metres above the hill, jamming it in between the existing structures. Parts of the house were also squeezed in the process; other parts envelop the surrounding houses or ruthlessly gnaw their way into them.

So, you see, this is not a building that has tired of the existing. It just doesn’t care that much. Or at least, that’s how it appears. All it wants is to go about its business with a natural confidence and an approach that bridges an apparent paradox. Because minimalism doesn’t have to be stripped down. Things can be simple and dressed up at the same time.

It’s as if the architects had a particular thing in mind when they conceived the building: the music video for ‘Sorry’ by Justin Bieber, danced and choreographed by ReQuest. It involves a lot of colours, powerful dynamics, spontaneity and humour – at the same time as the house oozes precision and quiet elegance. And just like Bieber himself chose not to figure in his own video, you might ask: where are the architects in all this? Did they simply dish out a beat and a rhythm and then leave it to others to take it the next step into the real world?

An ordinary townhouse, and yet ... The first floor seems to be the most interesting in terms of space and programme: a ramp leads up to an intermediate storey that provides contact outwards, upwards and downwards, linking three storeys and connecting with the busy street outside.

Letting the public functions take place upstairs and downstairs and the dwellings be served from the level where the ramp enters the building creates a strange dynamic. To reach your home, you need to pass through, or at least next to, both a bar and a shop but without entering into direct contact with any of these.

The internal colour scheme is radical too, as is the curious indifference when it comes to honest or natural building materials. On the other hand, there is nothing of the postmodern extravaganza about it, no bizarre forms or theatrical effects. If we stick with the idea of the house having fallen from the sky, then it’s more as if the entire house skewed a little when it landed between the other buildings. Not very much, not enough to make it come apart, but enough to offset everything a bit.

It’s not outré in any way or full of oblique angles or pasted-on elements. It’s not as if the apertures, skylights or fixtures, such as benches or tables, were deliberately disproportioned or asymmetrically arranged, or made from materials that contradict the structural logic of the house – like Skinrock or similar products that make you wonder if this is in fact stone or rather some composite material mixed with colour pigment.

What about beauty, then? True, I could have asked myself why the house looks like this. But then again, I won’t. Because I sincerely hope that the architects will answer: huh, whatever do you mean? Caught in the crossfire between conventional ideals, commercial demands for salability and a horizon where the architect’s energy is by definition earmarked for sustainability battles, this has become a profession where no aesthetic risks are taken.

So, not this time. With its seven storeys, which is one or two more than its neighbours, the at once arrogant and inconsistent approach to the context and, not least, an interior that doesn’t try hard to be different (so much for deliberately skewing things), this is not a house that one likes for what it is or what it does. But it will be loved for just being there. It’s a house that just woke up one morning and realized that things like spontaneity and precision are not mutually exclusive. Just like dynamics and deeper meaning aren’t.

Algorithms, I suppose – or wait a second: does it actually make sense to speak of honesty in a world where any alternative reality is just another algorithm? Because, surely, a house like that must be the brainchild of a computer, right? If Justin Bieber is the architect, then the roles of dancers and choreographers are perhaps played by designers and their sophisticated software? A digital generation 2.0, long after Frank Gehry and Guggenheim.

Or that would have been the obvious conclusion, were it not for the fact that its lines and shapes are so curiously inorganic. As if everything has been cut with a ruler and built in foam board before being realized in full scale. This house is as doubly curved as the worktop back in my own kitchen. As though it says: who cares if things are analogue and free-styled or digital and slick?

So there it is: a perfectly decent spatial programme with a pub in the basement, shops half a story up and an array of dwellings wedged in between the two and on the upper floors; and with most of it – apart from a few bits here and there – contained within the same structural shell.

Hehe? Maybe the random passer-by will think that this is all a big joke. But then again – is it really that funny? Or is it more a case of indifference? The notion that one thing is as good as the next and that anything goes? No, I don’t think it’s that either. There seems to be a genuine urge there to strive for beauty.

This is not a house you’re supposed to like, it’s more a matter of feeling the attraction. In which case it’s mission accomplished.