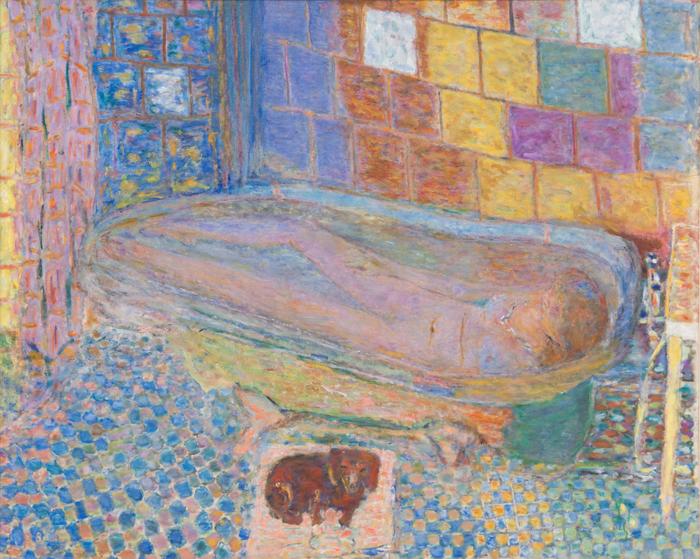

Pierre Bonnard, c.1940-1946, Nude in Bathtub, oil on canvas, 122.56 × 150.50 cm. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA / Art Resource, NY

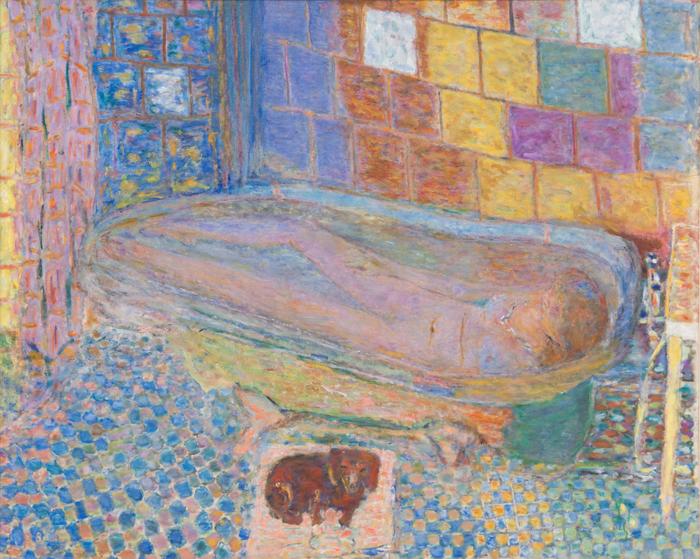

Pierre Bonnard, c.1940-1946, Nude in Bathtub, oil on canvas, 122.56 × 150.50 cm. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA / Art Resource, NY

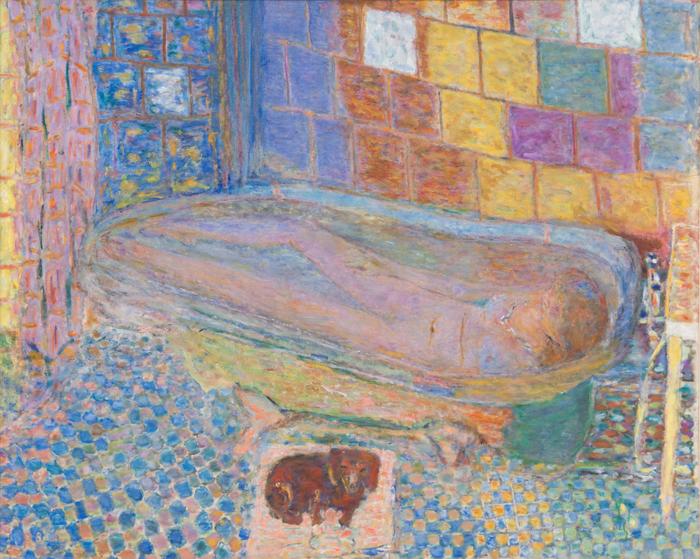

Pierre Bonnard, c.1940-1946, Nude in Bathtub, oil on canvas, 122.56 × 150.50 cm. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA / Art Resource, NY.

But you soon learn to become fluid. You vary yourself according to the wavelengths, you change your shape, your volume, your contour, and you then belong so completely to the space, that the flat lived in me, just as much as I did in it. Clarity of thought became one of its dimensions.

I was thinking more clearly, writing more clearly, because I was more clearly absent from what usually held me down. Almost nothing mattered anymore, just breathing and the sensation of being there, and thoughts cast out to meet with the world, with no concern for longitude, or latitude, for what is generally termed space.

- Marie Darrieussecq *

On Being and Bathing (2021, 09:45, 16mm) Anna Ulrikke Andersen with Abi Palmer

On film, it is sound that precedes sight. The tinkering of piano comes on just before a medium close-up of a face. It is framed by blue polyester, in a V, that cradles its chin. The film is pallidly bleached like a polaroid, and the subject whose pale blue eyes match the polyester, has blonde hair that complements the tonality of her surroundings. Everything is awashed in an afterglow of pale-ness. This lacking in vitality accompanies the melancholy of the piano and a voice that narrates. A moving train from the window puts you in the subject’s perspective as she stares listlessly at the external world. It is at this instance the narrator becomes the subject as the voice describes her experience moving to a new flat in London.

The subject then moves over to the object of an inflatable bathtub, of which the blue polyester belongs to. This object of interest provides the visual link to the narrative of accessibility and adaptability. What is at first flaccid, is preceded by what it is meant to do and become: inflated with the narrator’s breath to take up space and warm water in the bathroom. The serpentine chrome of the shower hose rests under the very thing that it fills the tub slowly with. This symbiotic relationship of volumes, chemical and organic, can also be described as an assemblage of polyester, breath, water, chrome and flesh.

It’s uncanny when she says swimming pool blue, because I associate that colour with the affective treatment of the film. It is that clinical blue of melancholy that pervades the film like an atmosphere. And she wears a bathing suit after all—one is not sure, as for the purpose of the film or if it is part of the therapy. When the film turns silent, one is reminded of being underwater, lost in thought. This viewer contemplates as he watches a vulnerable act of self-maintenance. It is more. It is also a sensual alleviation of pain, of forestalling gravity temporarily through an utterly remarkable yet banal substance. But it is unlike watching someone getting a massage from water. The film is shot in fragments and you never see the act in its entirety, neither the tub nor the narrator’s body. This suggests an interiority and that the narrator’s disability is as much invisible as it is visible, for you only see the symptoms of pain and not what is being felt in bone and muscle.

If bone and muscle are the architecture of the human body, then writing is the architecture of thought. Like the grab bars that support the body, words are the transverse of the paper document. The narrator, now the artist, writes sheets of notes that she puts up and makes puppet-like garments, both that maybe contradict each other. Words are fluid; they float up and are slippery, but the white gown that is trying to ascend with strings crumples back to the floor under its own weight. The film is cut with light leaks, or bits of sunshine as one scene transits to another.

The motif of the piano becomes discernible now as the camera gently closes and dissects the scene discreetly from a distance. Shoulder, face, eye-lashes, throat, hair and hands from a body that is resting but unable to dissolve in the water. What happens when one watches another rest, or bathe, or think? Unless one becomes conscious of the other, one is partaken in the act of being the one watched. I thought about the one time in Bangkok (plus a return visit) where I enclosed myself in one of those sensory deprivation tanks. They fill your bath up with a few hundred kilograms of salt and as you close the lid upon yourself, you float in pitch darkness and weightlessness. One then, escapes the gaze of the other and its image, as one crosses over from both the public and private into the void. Perhaps the void also comes from some paradox of nullification between life and death, sea and womb; water as a medium for oxygen and nutrients, and high salinity that would deter macroscopic organisms from living.

We return to the medium close-up of her face framed by blue polyester, in a V, that cradles her chin. The act nearing completion, the body exerts itself to get out of the tub to drain the fluid out of the soft apparatus. A glass of drinking water acts as a smaller model and spirit level nearby, whose equilibrium is disturbed as she tries to push her body back up onto the bathing chair. And this is when the camera offers a rare cinematic gift—A gelatinous pair of feet trying to remember land again, whose toes are still sleeping, delicately slumped against the non-slip tiles, whose heels have not yet borne the full weight of the body. The sound of water being drained succeeds completely after the scene runs out, only reprised by the end credits and a glimpse of the dusky world outside the apartment.

Pierre Bonnard, c.1940-1946, Nude in Bathtub, oil on canvas, 122.56 × 150.50 cm. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA / Art Resource, NY.

Three adjectives come to this writer at once: devastating, overwhelming and tender. I know these feelings might change over the course of this writing. I picked this particular image as the one I am most familiar with since I was an art student who wanted to paint. Actually, it was a different painting that inspired the writing. However, he must have painted dozens, if not countless paintings of the same woman bathing. Of course, before I began, a painting is very different from a film. For one, I am talking about a single image as opposed to a continuous sequence of frames that the eye cannot register. Time is therefore eternal, or memorialized as an index of gestures that derive from the artist’s hand. Secondly, I am looking at a reproduction of an actual thing that resides somewhere in a collection or museum, as opposed to a film, which always is a reproduction disseminated to be watched on different platforms.

Colour and light dance in a kaleidoscopic mosaic of sensations. They pulsate with a radiant warmth that saturates the whole picture. The subject’s slender body, perhaps elongated in the painting, is stretched comfortably to the length of the tub. Squares of white light hit certain tiles to provide interest as if seen as an abstract composition. It seems she has been in there for a long time and I cannot tell if her body is warming the tub or that the tub is warming the body. Phenomenologically speaking, what the previous artist in Act 1 desired for herself is happening to the woman of the painting. By proxy of the painter, she is close to dissolving in the tub of water as one entity. Something comes to mind now, it is as if I am looking at a watery shallow grave. Orphelia. You remember Ophelia as she floated on her back, contemplating her death. But the body here is still warm, in complete repose. Only her right shin, her breasts, and the top of her head are cool to the touch, perhaps because they are the parts furthest from the water.

Today, she is luminescent with colour. In fact, she is dissolving into the whole painting, or that the whole painting becomes her. The more I try to make out her head, the more it ends up as a mash of daubs and strokes. It is the most disfigured and corporeal part of the painting. It is the part most touched upon and revisited by the painter. In comparison, the dog in the painting is a flat motif plastered on the floor mat at the lower centre of the painting. It is the only thing that looks back at you. The floor tiles are the most palpable. They are shiny pieces of blue ceramic that warm up and catch the light and lend a touch of bohemia to the painter’s sunrise sunset palette.

I feel it is more sunset because of the tonality, brilliance and overall mood. I now see that the curtains are drawn to allow light, or more colour in.+ Part of the piping and the side vanity table is captured as it goes off the edges of the frame. Did he stand and watch over her from an easel, while she bathed?

Why does one watch a film, but look at a painting? Perhaps it has got to do with the fact that a film is regulated by time and you wait for things to happen so you watch what happens. But in a painting, the elements remain static, there is no animation, and you may choose to ignore and look away. But when you stop to look, and stare, something then happens. The painting responds back.

There is a second difference, between a painting and a film, that happens outside the painting. It has to do with the fact that modern paintings onwards had become silent and all the narrative, captions and rhetoric had gone. Sometimes, the viewer struggles for entry points to find understanding and meaning other than the pleasure of looking. For this particular work, the painter had painted his wife bathing one last time, who suffered from an ailment, or illness, or a malady that needed constant hydrotherapy. He made countless paintings of her in the tub, by the tub, or preparing the tub for her remedial routine. The painting is as much a brilliant study of colour as it is a poignant tribute to his partner.

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975, 201 minutes) Chantal Akerman, Collections CINEMATEK - © Fondation Chantal Akerman

It is a four-minute bath here and the tub is concomitant with routine, and not luxury. The woman is, for a brief period of time, confined within the cinematic box of the camera, which records time unobtrusively as it is. One hears the sound of the running hot water tap. This act is something between the first two acts: too silent to be narrative and too brief to be a painting. Yet it also stands out from the two for its stark realism, where the two before were impressionistic. Bathing is treated as a task among many tasks to do and treated just the same. This same-ness actually pervades the whole three-hour film. Some say monotony, but I much prefer monochromy as an aesthetic observation; this treatment of an undifferentiated surface of time brought about by both modern art and photography. Filmed with a straight-on perspective without cuts, it is one of the most monochrome films that I have seen.

One cannot bear too much of the real. Time is perpetually recurring and capitalist. Let me explain. Here, time is run by economy and the clock, and things have to be done by a set period. Economy runs throughout the film. From the way the film is shot to the prudence and frugality of the character. This might be a European thing (I coming from Southeast Asia), in cold weather, but the sponge bath and careful use of the tap suggest a kind of prudence and economy with time and resources, instead of lying in a tub full of water. There are no distractions in the film. This becomes a prime example of how technique marries subject, form merges with content. One becomes utterly transfixed by this scene and at the same time, one becomes uneasy, watching a woman bathe, because you are self-consciously aware of being a witness here. In fact, what should be alienating finds the most identification with me because upon watching this again, it is no longer just an aesthetic treat. I had unwittingly become a homemaker myself, but in a largely circumstantial sense, bogged by the burden of maintenance, domestic routine and economic realities. However, this character performs this labour not only everyday for herself without recompense, but also on demand for you the viewer. What should have been a respite for reflection and self-care becomes alienated, insurmountable and unbearable instead.

I want to move on and talk about the scene itself and why it is special. The woman is filmed from a side profile sitting in the bath. It is not confrontational like when filmed from the front, or voyeuristic and diminished when filmed from the back. It is discreet enough, and you get a complete perspective of the architecture, yet, you never get the full picture. I always feel as a photographer, painter or filmmaker, when you portray a figure from the side, you offer the viewer the possibility of the subject’s interior monologue. Unlike Act 1, you never hear her thoughts. This renders the scene more opaque as the subject is not completely permeable. She becomes an object when you notice how her skin tone matches the coral pink wall above, which are complemented by the grey-green marble tiles. The carefully coiffed curls of her perm remain untouched during the bath. The caesura of the film happens when Jeanne has an empty interval in her routine, due to waking up an hour earlier. Her anxiety takes over and she does not know what to do, and things start to unravel in a concatenation of negligent incidents, that lead to an event of drastic proportion concerning a pair of scissors. This measure by the director seems to be taken as if to stimulate the viewer back into our fantasy with death and violence, perhaps to end our profound boredom.

I change my mind—it is not alienating, insurmountable or unbearable. It was my initial perception. In my second draft of writing, I am tasked to confront maybe this weak paragraph that tries to tie things up too soon, too neatly or correctly. How to conclude? Well, I said before this act defines her and gives her ownership and control over things that are beyond her own. It’s a woman’s labour and pride of house and her dignity to take care of herself that frees her from insurmountable forces. This busy-ness and consistency to fill one’s heart and mind surely is enough for one to exist. I ignore the previous metaphors then. But this is not it. Neither is it how this scene punctures previous representations of women in film. I come back to this line again: “what should be alienating finds the most identification with me because upon watching this again, it is no longer just an aesthetic treat.” I had unwittingly become a homemaker myself. I fucking hate housework, but recently I had begun to be more present doing my chores, and though it has not reached the stage of religious routine, like prayer, it has become somewhat occupying and fulfilling, duration-rich in an event such as doing the dishes. It became somewhat bearable—habits begin to form familiar shapes, and that line from Beckett started to make sense, something about how the creation of the world did not take place once and for all time, but happens every day. So, a little Zen goes a circular way.

I also think sometimes writing too, like bathtubs here, approximate memory and volume through their qualities—pneumatic, painterly, and concrete.

* Marie Darrieussecq; Decosterd Rahm (2005), Ghost flat : (a modern couple), Kitakyushu, Japan : Center for Contemporary Art.

+ I would like to raise a caveat here, that I was looking at a digital reproduction on my laptop in my initial reading, which was not true to the actual colours of the painting in the collection of the Carnegie Museum of Art. While trying to obtain the copyright for the image, I found the closest reproduction as per the Museum website. It proved to be less saturated and more pastel.

“When I first read Jeremy’s essay, I felt uncomfortable reading his take on my work. I was worried he had felt forced to write about my film. Was he being too nice, not wanting to critique my work? But as the essay developed, I realized that perhaps his writing style – exploratory and genuinely curious – marks his approach and that the combination of three case studies is what offers a new perspective. I would, however, like to push the conversation regarding points of view further. What does it mean to be up close, watching from above, or remain quiet and measured, framing someone else from a distance?”

“I very much enjoyed being encouraged to think, further about the act and implications of looking. I also really liked the final section in which Jeremy refers to the project writing workshops and how the feedback in those informed his own thinking and the development of his essay. I think Jeremy’s essay also raises many of the same questions in the reader/viewer, namely ‘should I be looking? I have related concerns within my own writing; should I be the one to be looking? Should I be the one to be recording what I see? My writing are often very personal in nature but inevitably will draw in friends and family members as I recall my own experiences. Should I be retelling these stories about myself if they can’t be told without a portrait of another (innocent) person?”

Jeremy Sharma, “Three Acts of Bathing—an-other reading,” Metode (2024), vol. 2 ‘Being, Bathing and Beyond’