Up Helly Aa act Small Fry in Oil, mask-on picture, 1974. Photo from the Up Helly Aa Committee’s Archive.

Up Helly Aa act Small Fry in Oil, mask-on picture, 1974. Photo from the Up Helly Aa Committee’s Archive.

Up Helly Aa act Small Fry in Oil, mask-on picture, 1974. Photo from the Up Helly Aa Committee’s Archive.

The Shetland Islands are a Scottish archipelago that lie approximately 480 kilometres north of Edinburgh and 320 kilometres west of Bergen, on the crossroads between Norway, Scotland, and the Faroe Islands. Shetland houses Sullom Voe, one of the biggest oil terminals in Europe.1 During peak times, up to 1.5 million barrels of oil daily enter the archipelago from the oil platforms out in the North Sea to be stored in underground containers, after which they are shipped to ports all over the world.2 When the current of oil runs smoothly and uninterrupted through the pipelines underneath the Shetland Islands, it is largely invisible to the roughly 23,000 inhabitants living here. In different periods throughout history, however, the concealed flow of oil became visible and was subsequently discussed, performed, and criticized by members of the Shetland community.

Following Godfrey Baldacchino’s call to treat islands as quintessential sites of innovative conceptualizations3, this text explores how energy discourse is being shaped through theatrical acts happening within rural festivals in Shetland. As an island group often cramped in an inserted box on maps of the United Kingdom and jokingly called the “inset islands,”4 yet on the “frontline”5 of oil production and green energy developments, Shetland makes a fitting case study of the creative reactions of island communities on energy transitions in the North Sea.

The specific material in the Shetland culture through which I will reflect on the creative mediations of energy consists of what I came to call “energy acts.” These short theatre acts happen in the framework of the carnivalesque and myth-themed Up Helly Aa festival. By using Mikhail Bakhtin’s (1895-1975) theories of folk culture to discuss a handful of historical acts that I found in the Shetland Archives, I will provide a creative timeline of oil’s first decade on the islands. By doing so, I will simultaneously discuss the energy act’s aesthetics and inherent environmental and social critiques. This undertaking will be followed up next year when I will re-enact some of the energy acts in light of the opening of the new Rosebank oil field north-west of Shetland, which is planned to start operating in 2026.6

The philosopher and literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin was concerned with the use of humour and art in folk culture. His theories about carnival (1984) serve in this essay as a contextualization of how the Shetlanders used laughter and the logics of the grotesque to communicate their observations and displeasures about oil production in the 1970s. By morphing news, myths, and popular media stories in their acts, the Shetlanders created satirical and fantastical forms which enabled them to “act” on oil. I am ultimately interested in examining the usefulness of Bakhtin’s theories for the Shetlanders’ festival, exploring how we can see community-fuelled creativity as a medium in the shaping of energy discourse.

Bakhtin’s theories about carnival as a social reaction to authoritarian (state) power is especially alluring in relation to the rise of the oil industry in Shetland. The oil industry gained accelerated political agency in the last fifty years and is still described as “the principal industry associated with Shetland.”7 Community centres, schools, and island infrastructure are partly funded by Shetland’s oil chest, setting the archipelago apart from other British isles that are more dependent on British government funding. Oil also formed and restructured Up Helly Aa as a festival. For example, the participation of temporary oil workers is regulated through a special rule that was established in the 1980s.8 As historian Callum G. Brown points out, oil also resulted in more Up Helly Aa editions in rural parts of Shetland, as more funding became available after the finding of oil and the Shetlanders’ economy generally improved.9 My own research, however, is less concerned with these practical and economic effects of oil on Up Helly Aa. Instead, it questions the creative ways in which oil shows up in the costumes and through the acts of the participants. In line with Bakhtin, I ask how the Shetlanders’ carnival is directed at communicating the effects of oil production in creative and imaginative ways.

1 EnQuest PLC, “Sullom Voe Oil Terminal,” EnQuest.com, March 2019, accessed 8 October 2024, URL: https://www.enquest.com/fileadmin/content/operations/ICOP_PDFs/EnQ_ICOP_Sullom_Voe_Terminal_2019_03_28.pdf.

2 Chris Cope, “Forty Years and Counting for Oil at Sullom Voe” Shetland News, 23 November 2018, accessed 8 October 2024, URL: https://www.shetnews.co.uk/2018/11/23/forty-years-and-counting-for-oil-at-sullom-voe/.

3 Godfrey Baldacchino, “Islands as Novelty Sites.” Geographical Review 97, no. 2 (2007): 165-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2007.tb00396.x.

4 Nick Bearman, “Scotland’s Most Remote Islands Don’t Want to Be in ‘Inset Maps’ Any More.” The Conversation, 6 November 2018, accessed 8 October 2024. URL: https://theconversation.com/scotlands-most-remote-islands-dont-want-to-be-in-inset-maps-any-more-106139. Laura Watts, Energy at the End of the World: An Orkney Island Saga, Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2024, 43.

5 Kofi Annan, UN secretary, United Nations, 1999, quoted in Godfrey Baldacchino, “Islands as Novelty Sites,” in Geographical Review, April 2010, 166.

6 BBC News Office, “Rosebank Oil Field: What is the Row Over the Project?”, BBC News, 27 September 2023, accessed 8 October 2024, URL: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-66933832

7 Ian Napier, Shetland’s Maritime Economy (Shetland: UHI, April 2022), 20, URL: https://www.shetland.uhi.ac.uk/t4-media/one-web/uhi-shetland-images-and-documents/research/statistics/economy/Shetlands-Maritime-Economy-2022-04.pdf.

8 Callum G. Brown, Up-Helly-Aa: Custom, Culture and Community in Shetland. (Manchester: Mandolin Press, 1998), 174.

9 Brown, Up-Helly-Aa, 197-199.

Up Helly Aa. Burning of the Viking galley. Photo: Miriam Sentler, fieldwork January 2024.

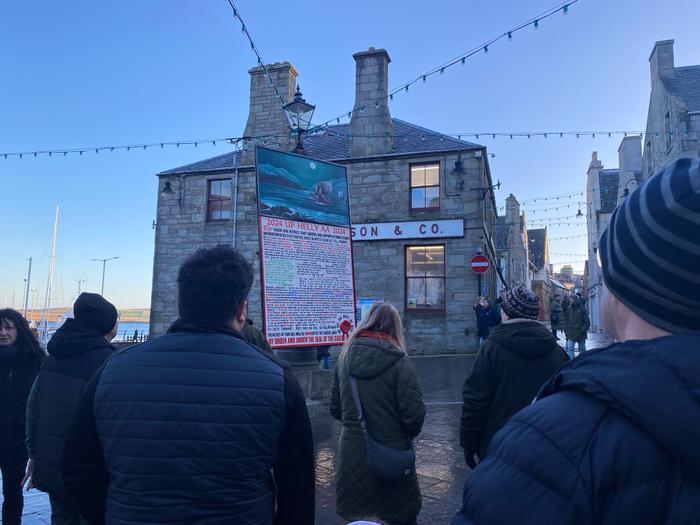

Up Helly Aa. The Bill in the Lerwick marketplace. Photo: Miriam Sentler, fieldwork January 2024.

Since 1873, Up Helly Aa (hereafter UHA) has taken place across the Shetland Isles from the end of January until March of each year.10 The festival in Lerwick is the largest one, but also ten smaller versions of the festival take place throughout the islands.11 Different forms of the Lerwick festival have existed long before its documented start in the Victorian era, during which it was melted into a loosely Viking-themed celebration by working-class men interested in the Viking history of the Shetlands. The Viking theme was further manifested under the influence of intellectual figures on the islands like the blind poet Haldane Burgess, who wrote the Up Helly Aa song in 1905.12

In its current format, the festival starts with the instalment of “the Bill,” a satirical text commenting on recent events on the islands. The Bill is placed in the marketplace of Lerwick on the morning of the festival. This instalment is followed by a parade of so-called guizers, a name given to the men (and since 2024 finally also women)13 in the torch-lit procession. Towards the end of the festival, a replica Viking boat is set on fire in the middle of a children’s playground in Lerwick, after which the squads (the name given to a group of guizers) dissolve into the night and visit the Halls, which are locations in various school buildings and community centres. Here, they perform light-hearted acts until the early morning.

Taking place in the depths of winter on a stormy island group, Up Helly Aa is a rather inward-looking festival, marking the start of a new year by looking back and making fun of the old one. The winter in Shetland is a time in which transitory visitors – whether the merchants, sailors, whalers, and fur traders of previous eras, or today’s tourists and temporary oil and green industry workers – are mostly absent and the “inside” community comes out to reflect on global and local events impacting their islands in the past year.14 Or, to place it in line with the carnival described by Mikhail Bakhtin, the festival has, “as it were, the two faces of Janus. Its official, ecclesiastical face turns to the past and sanctions the existing order, but the face of the people of the marketplace looks into the future and laughs.”15

In line with Bakhtin’s description of carnival culture is also the custom of electing a king for a day.16 In Up Helly Aa this happens in the form of electing a main figure of the festival, known as “Guizer Jarl,” who leads the Viking parade through town. The Guizer Jarl is chosen fifteen years in advance by the Up Helly Aa Committee, during which he prepares “his” Up Helly Aa edition by fundraising, making costumes, and choosing his Jarl Squad.17 It is therefore always a figure intrinsically connected to the island community. Existing ranks and status symbols no longer matter during Up Helly Aa, as the Shetlanders are “temporarily suspended from hierarchy”18 and are being “reborn for new, purely human revelations.”19 Even the fire brigade and police take part in the festivities, with almost one-sixth of the total population of Lerwick carrying a torch that night.20 Lastly, laughter is used within the festival as an “interior form of truth,”21 mocking authority by highlighting recent local events, like the missteps of certain government officials or the plans of multinational oil firms. This is often done by referring to fairytales, myths, or social media and television trends. Which squad gets the loudest laughs and makes the most timely act at the Halls wins the hearts of the audience. But keep in mind that this is no competition.

During the winter of 2024, I witnessed Up Helly Aa in person for the first time. The festival spanned the whole day and night, starting out in the bright morning sunlight at the Lerwick harbour, where the Viking squad posed for their group photo. Later that day, I found myself standing next to most of the Lerwick community around the city hall, watching groups of guizers coming by while we were all being battered by the severe wind and rain that the North Sea was sweeping over the islands. My eyes were tearing from the oil smell and smoke coming from the burning torches, and later I found myself drinking tea and eating sandwiches at four o’clock in the morning in a neon-lit elementary school auditorium. Groups of men performed comical acts on the floor, in front of a loud, euphoric group of islanders cheering them on. At the end of the night, I saw an act titled “Just Stop Oil Now,” seemingly making fun of the campaigns of recent environmental activist groups in Scotland targeting the infrastructure of the oil industry. Participants playing members of the well-known activist group blocked the Highland Fuel trucks by gluing themselves onto the pavement. What followed was a comical act in which various government officials tried to remove them. All this made me wonder if there were other acts about oil to be found in Shetland’s archives.

10 Ibid., 14.

11 Promote Shetland, “Up Helly Aa Fire Festivals,” Shetland.org, accessed 8 October 2024, URL: https://www.shetland.org/visit/do/up-helly-aa-fire-festivals.

12 For a broader understanding of how the Viking figure became adopted in Up Helly Aa, see: Callum G. Brown, Up-Helly-Aa, chapter 5, “‘Perfectly in Custom’: The Birth of Up Helly Aa” (126-155) and Brian Smith, “Up-Helly-Aa: Separating the Facts from the Fiction,” The Shetland Times, 22 January 1993.

13 Ken Banks, “Women and Girls Make History at Up Helly Aa Fire Festival,” BBC News, 31 January 2024. URL: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c29klnxyk06o. For more information about the gender-controversy and history of protest in Up Helly Aa see: Finkel (2010), Johnson (2019), Attorp (2022), Dye (2023).

14 Brown, Up-Helly-Aa, 65.

15 I altered this quote from the past to the present tense. See Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), 81.

16 Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, 81.

17 Up Helly Aa Committee, “Guizer Jarl and Jarl Squad,” uphellyaa.org, accessed 8 October 2024, URL: https://www.uphellyaa.org/about-up-helly-aa/jarl-squad/.

18 Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, 89, 10.

19 Ibid., 10.

20 Adam Civico, “What Happens on Lerwick Up Helly Aa Day?” Shetland.org, accessed 8 October 2024. URL: https://www.shetland.org/blog/what-happens-lerwick-up-helly-aa.

21 Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, 94.

Up Helly Aa Committee meeting room and archive.

Photo: Miriam Sentler, fieldwork January 2024.

After the festival I worked with the head archivist at the Shetland Archives to collect different mentions of oil and other energy sources in the local newspaper The Shetland Times, spanning roughly the last fifty years of UHA (1972-2024). This archival research resulted in a collection of around thirty energy acts. Going into the archives of the Up Helly Aa Committee later that week, I found the supplementary mask-on/ mask-off pictures in a series of ridiculously large photo albums that were almost too heavy to hold on my lap. Distilling a few examples from this collection for the following part of this text, I now want to research in detail how energy discourse is historically shaped, aestheticized, performed, and otherwise mediated by Shetlanders with the help of myths, humour, rituals, and television trends that play a large role in the myth-themed and carnivalesque festival. The selection of acts is based on the attention on oil-themed topics, expressed in the costumes and the way in which the script smartly centres attention on oil-related developments in Shetland through satire and the image of the grotesque. They are all from the first ten years of oil operations in Shetland (1972-1982), which makes them roughly fifty years old. This was when the oil industry was still a new and much-discussed topic in Shetland and when the Up Helly Aa costumes were – in my personal opinion – at their peak.

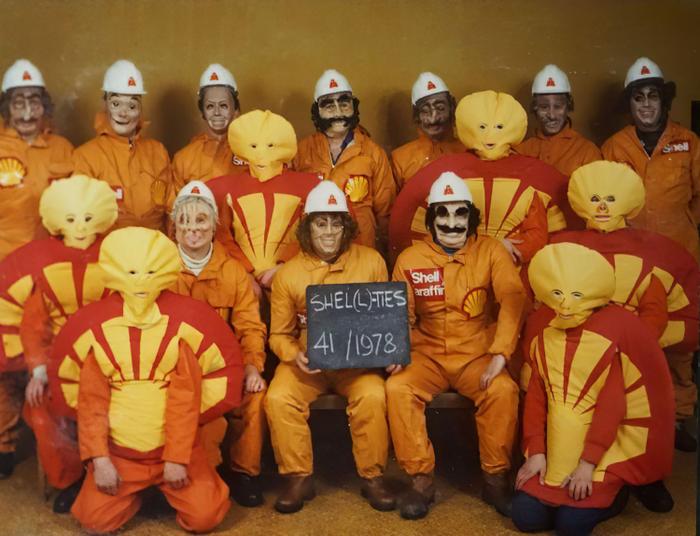

“The squad represented the well-known oil firm. Six members were dressed as the character seen on the tv advertisement and the remainder in bright yellow boiler suits with various Shell insignia attached. Cars describing various oil firms had a race with many mishaps.”22

– newspaper reporter, The Shetland Times, 3 February 1978

The act Shel(l)ties takes us back to the beginning years of the oil industry in Shetland. Before and around the discovery of oil in the Norwegian sector of the North Sea in 1969,23 different oil firms in Britain prepared for their big find, starting a relentless competition for offshore oil drilling licenses. In 1971, it was Shell/ Esso that first found oil north-east of Shetland in a location that would later become known as the Brent field. The discovery was initially hushed up by the company, creating a lot of gossip and hearsay in the Shetland archipelago.24 As Shetland was the closest island group to the drilling site, noble plans for a slow-paced growth in the islands’ rural economy were soon swept aside as the archipelago got adrift in a movement that we know nowadays as the North Sea oil boom.25 The race for drilling licenses and the ways in which the different oil companies introduced themselves to the islanders through the brand-new media of colour television26 is captured in the act Shel(l)ties (1978).

The act makes use of a symbol that must have been known to the island community from a series of television commercials that were aired in Britain around 1975. In these television commercials, we meet an optimistic-looking Shell logo that sings and dances its way through the global cargo-supply chain of oil: starting from the oil-spilling deck of an oil platform in the North Sea and making its way onto airplanes and fancy sport cars. The opening of the Shell logo’s song goes as follows:

Who’s working hard on the North Sea Swell?

You can be sure it’s Shell, Shell, Shell!

Exports as well, all going well –

Britain goes better with Shell!

22 The Shetland Times reporter, “What the Squads Did and How They Looked.” The Shetland Times, 3 February 1978, accessed in the Shetland Archives in Lerwick, UK, 25 January 2024.

23 The Ministry of Energy and the Norwegian Offshore Directorate, “Norway’s Petroleum History,” Norwegianpetroleum.no, accessed 8 October 2024. See the URL in the bibliography.

24 James R. Nicholson, Shetland and Oil (London: William Luscombe Publisher Limited 1975), 49.

25 James R. Nicholson (1982) quoted in Archie E. Hill, Carole L. Seyfrit, and Mona J. E. Danner, “Oil Development and Social Change in the Shetland Islands 1971-1991” in Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 16, no. 1 (1998), 16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.1998.10590183.

26 Colour television was introduced in Shetland in 1976 as the last place in the United Kingdom. See: RainbowSilver2ndBackup, “File: Timeline of the Introduction of Colour Television by Decade.svg,” Wikimedia Commons. URL in the bibliography.

Shell advert 1975

Instead of sticking to the glamorized storyline of globalization which is told by the Shell logo in the advertisement, the Shetlanders chose to relate the video aesthetics to mundane symbols from their direct living environment. By doing so, they related the video to their own experience of being at the centre of competing oil firms in the North Sea. One symbol of Shetland culture used by them in relation to Shell is the Sheltie, or Shetland Sheepdog, resulting in the merging of both names in the act’s title Shel(l)ties. In the energy act, we see sixteen men, nine of them dressed in bright, orange boiler suits resembling the working suits of oil industry workers. All of them have shiny stickers of Shell logos on their chests, and one of them bears a logo stating “Shell Paraffin.” The men in the back wear masks with crinkly, distorted faces and drawn-on smiles, fake hair, safety glasses, and white safety helmets. In front of them we see six Shel(l)ties: men dressed in suits resembling the Shell logo, seemingly made of synthetic parachute-fabric in shiny red and yellow colours, spanned over a frame. They wear yellow, shell-formed masks with cutouts for eyes and mouths, with sideward noses drawn upon the fabric and one nose from the guizer on the far right dramatically sticking out from under the mask. Maybe this particular guizer had trouble breathing through his mask. Two of the Shel(l)ties are kneeling, in a seemingly submissive, dog-like pose.

The choice of relating the friendly-looking Shell logo to the submissive, barking Shetland Sheepdog touches on the transformative characteristics of carnival posed by Bakhtin. He describes how the forms of animals, humans, and plants all become interwoven in the grotesque image,27 “as if giving birth to each other.”28 In the costumes of the Shel(l)ties we can identify the demeanour of dogs, oil workers, and mussel shells, all mixed up in a new, playful form. These entangled bodies subsequently become alive in the act and race each other, displaying a satirical parody of power by referring to the competition of the different oil companies. The oil workers in the background are displayed with grotesque grimaces, dehumanizing them and making them look almost puppet-like. Through a performative play of satire that mixes human, animal, and inanimate bodies in a single, grotesque assemblage, the act thus seems to dissolve any form of authoritarianism29 that the different oil firms might have superimposed on the island community during this time. The image of the mussel shell is comically enlarged in the costumes, becoming a hyperbolic natural entity “swallowing up” the bodies of the guizers.30 Also this is a symptom of the grotesque.

27 Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, 32.

28 Ibid., 32.

29 Ibid., 90.

30 Ibid., 317.

Up Helly Aa act Shel(l)ties, mask-on picture, 1978. Photo: the Up Helly Aa Committee Archives.

Up Helly Aa act Shel(l)ties, mask-off picture, 1978. Photo: the Up Helly Aa Committee Archives.

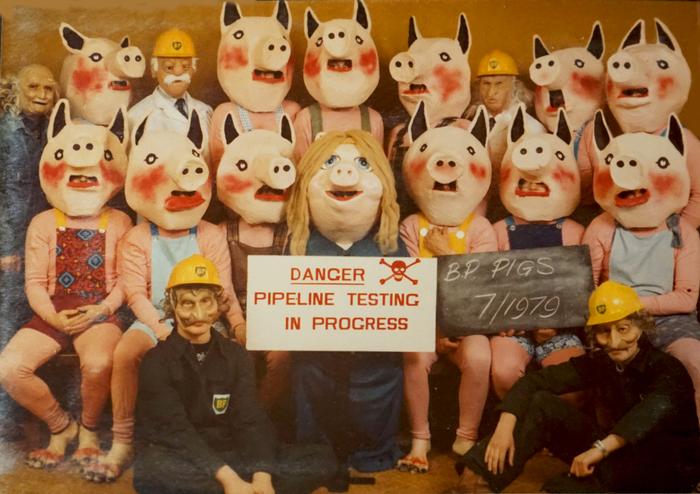

“Recent pipeline testing by the oil industry using Pipeline Inspection Gadgets (PIGs) was used by the squad to illustrate the problems when a pig gets stuck in the pipeline. Twelve members were dressed in pig costume complete with large head and snout. Two were dressed as oil technicians, who, after failing to persuade the pig through the pipeline, had to call for assistance which came in the form of the Muppet pig – Miss Piggy – who danced seductively before the entrenched pig who immediately shook himself free and gave chase to Miss Piggy followed by the remainder of the pigs and two confused boffins [i.e., researchers].”31

– newspaper reporter, The Shetland Times, 2 February 1979

31 The Shetland Times reporter, “What the Squads Did and How They Looked” in The Shetland Times, 2 February (1979), accessed in the Shetland Archives in Lerwick, UK, 24 January 2024.

Oil pipelines being laid in Shetland, photo: shetnews.org.

A pig (Pipeline Inspection Gadget), photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Followed by the premature years of the oil industry on the Shetland Islands with its hiccoughs and accidents, safety became of an accelerated concern, resulting in a series of new technologies being used by the oil industry. An example of these new technologies were the “pigs” that had the function of cleaning out and optimizing pressure in the oil and gas pipelines leading under the Shetland Islands and through the North Sea. Many Shetlanders had an active interest in the oil industry developments, as they directly and indirectly affected their lives on the islands. The unquenchable thirst for news about the oil industry’s development plans in the North Sea resulted in 1978 in a separate newspaper issue curated by The Shetland Times, titled Oil News. This newspaper seems to have served as an extra issue providing more in-depth news about oil developments, as The Shetland Times was already overspilling with articles about the oil industry, ranging from news about contractors and oil firms to the coverage of an oil spill at Sullom Voe oil terminal on 22 January 1979.32

The energy act BP Pigs (1979) seems to hint at this oil news circulating over the islands, making fun of Pipeline Inspection Gadgets, commonly referred to as “pigs.” By doing so, the act possibly expressed prevalent confusion amongst the Shetland community about the technological terms and internal oil industry jargon that was picked up by the newspaper reporters of The Shetland Times in the 1970s, as they desperately attempted to display “what was going on” with oil in Shetland.

In the energy act, the squad merged the oil industry’s “pig” jargon with the TV character Miss Piggy, a famous figure from The Muppet Show. In the act we see a group of eighteen Shetlanders, thirteen of them dressed as pigs. All of them wear masks, the large and clumpy pig masks possibly made from papier-mâché, with powdery pink and black paint on them and an opening in the pig’s mouth through which the Shetlanders could breathe. We see noses sticking out of the mouths of the pigs: a comical display. The pigs wear colourful outfits made of different fabrics with playful patterns, with pink leggings and sweatshirts underneath and socks with pig hooves painted onto them. The masks of the oil workers are artfully made with large noses and hair extensions. The oil workers are dressed in black boiler suits, adorned with the logo “BP” (referring to the firm BP, or British Petroleum) and white lab coats, possibly referring to the chemists working for the oil industry. All of them, except a creepy figure in the upper-left corner, wear yellow safety helmets with the BP logo. Miss Piggy, sitting in the middle with an elegant, blue dress, yellow hair, and large blue eyes, holds a sign with a skull symbol saying “Danger: Pipeline Testing in Progress.”

The exaggerated, large heads of the pigs, with their gaping mouths, clumpy lips, pig hooves, snouts, and upward-standing black ears, can certainly be read as a fitting portrayal of Bakhtin’s image of the grotesque.33 But also the topic of the act seems to touch on the logics of the grotesque, emphasizing a storyline in which a pig gets stuck in a pipeline, an image loosely relatable to the archetype of childbirth. Following this logic, the oil pipeline becomes the birth canal and a grotesque play between the body’s upper and lower stratum unfolds, as the two oil technicians standing under the entrenched pig are pushing its buttock through the pipeline.34 The topic of the inability to “deliver” (in this situation the inability of getting the pig out of the pipeline to restart the flow of oil, causing distress amongst the oil chemists) is also a typical motif in the grotesque logic.35 In this case, the grotesque logic is targeted at showing the oil industry’s impotence. According to Bakhtin, also the combination of human and animal parts is one of the most ancient forms of the grotesque,36 and Miss Piggy incorporates this merging of different bodies in a way that was at once recognizable and comical to the Shetlanders.

3 See a newspaper advertisement on Oil News (p. 16) in The Shetland Times edition of 3 February 1978 and The Shetland Times edition of 2 February 1979.

33 Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, 317.

34 Ibid., 308-309.

35 Ibid., 308.

36 Ibid., 316.

Up Helly Aa act BP Pigs, mask-on picture, 1979. Photo: the Up Helly Aa Committee Archives.

Up Helly Aa act BP Pigs, mask-off picture, 1979. Photo: the Up Helly Aa Committee Archives.

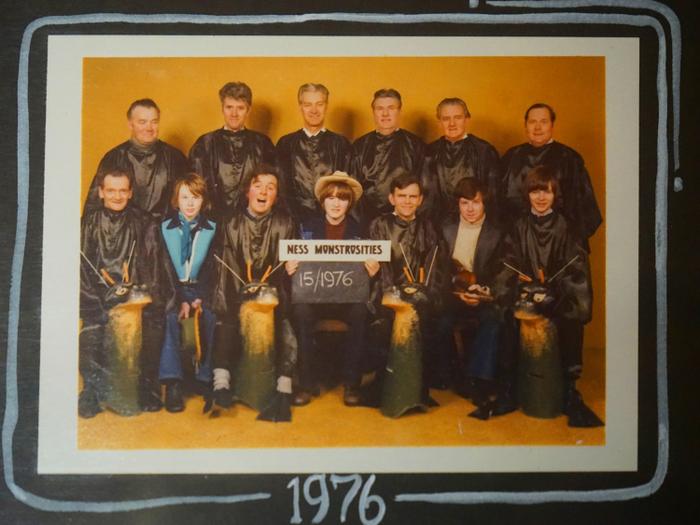

“A reference to both the recent furore about the Loch Ness monster and about the proposals to put oil in underground caverns on Calback Ness, this squad appeared as a team of monsters each bearing the legend ‘Loch Ness Migrants – Calback Ness Caverns Dweller.’ Members wore long black necks topped by dragon type heads in green and yellow, with black bodies and yellow spots. Fins and flippers completed the suit.”37

– newspaper reporter, The Shetland Times, 30 January 1976

As we can read in the newspaper description of The Shetland Times, this last energy act reacted to “recent [national] furore” about the Loch Ness monster. This phrase most likely refers to the scientific naming of the mythical creature in the year prior to the act. In 1975, the Loch Ness monster was named Nessiteras rhombopteryx by scientists Sir Peter Scott and Robert Rines, who pointed out that recent British legislation under the 1975 Conversation of Wild Creatures and Wild Plants Act only granted environmental protection to species which were previously granted a scientific name.38 The Loch Ness monster’s scientific name is of a descriptive nature, translating to “Ness monster with diamond fins,” which again refers to a presumed sighting of the Scottish monster in the lake Loch Ness on a 1972 expedition. This expedition was led by the Academy of Applied Science from Boston, Massachusetts, which combined the brand-new technologies of sonar scanning and underwater photography in a hunt for the mythical animal. During this expedition, the researchers detected a “large, underwater object” in the Scottish lake. A photo of questionable quality “appeared to show what vaguely resembled the giant flipper of an aquatic animal.”39 The presumed sighting and subsequent naming of the mythical animal led to much news coverage and discussion in Scotland.

37 The Shetland Times reporter, “What the Squads Did and How They Looked” in The Shetland Times, 30 January (1976): 10. Accessed in the Shetland Archives in Lerwick, UK, 26 January 2024.

38 Sir Peter Scott and Robert Rines, “Naming the Loch Ness Monster” in Nature 258 (1975): 466-468. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/258466a0.

9 Scott and Rines, “Naming the Loch Ness Monster.”

The original “flipper photo” (Image: AAS, source: http://tetzoo.com/blog/2020/8/17/loch-ness-monster-flipper-photos).

Photo of the trial tunnel at Calback Ness from J. R. Nicholson's Shetland and Oil (right).

The resurfacing of the myth must have renewed the interest of British city dwellers in the remote and romanticized parts of Scotland, namely, the Highlands and Islands, of which Shetland is a part. In the context of oil production in these remote places, I argue that the myth also renewed attention to the cultural imagination of rural Scotland’s geography, geology, and wildlife. The Shetlanders subsequently smartly reworked the myths’ fantastical story to articulate infrastructural critique on policies concerning the storage of oil on their precious islands. The media attention around the national resurfacing of the Scottish myth was thus used for site-specific reasons and in relation to the oil industry’s container question by the Shetlanders.

The aesthetics of “Nessie” proved highly useful to the energy act’s performative nature, as its makers were looking for a recognizable symbol which could be freely reworked within their acts’ inner logics. As mythology-scholar William G. Doty (1987) wrote, “myths provide opportunities to perform the world” as they produce useful images and symbols that can function as “aesthetic devices.”40 In the act, we see a group of thirteen Shetlanders, ten of them wearing what seem to be long, painted cardboard tubes on their shoulders, resembling Nessie heads. The monster has antennae reaching from its head into the sky, small orange tubes as horns, and a face with big rectangular eyes and a snout. Underneath the masks, the guizers wear a grey-black robe made of a shiny, printed fabric, shiny black trousers, and diver flippers (mostly out of the picture in the mask-on picture, but visible in the mask-off picture). There are also three boys wearing flared denim jeans, with cowboy hats and ’70s-style jackets and silk scarfs. One of them holds a violin, possibly referring to Shetland’s music and folklore culture, and another one holds a white sign stating “Ness Monstrosities.” The boy sitting on the left looks outright surprised into the camera.

Relating this last energy act to Bakhtin’s theories, it brings us straight into the worldly landscapes of the grotesque, or, in his own words, into the “mountains and abysses, such is the relief of the grotesque body; or, speaking in architectural terms, towers and subterranean passages.” To Bakhtin, these dwelling places formed a direct bridge to the bodily excrescences, like sprouts, buds, and orifices, “that (…) lead beyond the body’s limited space or into the body’s depths.”41 With Bakhtin’s logic of the grotesque, we can thus extend the grotesque body into natural abysses, like holes, or in the context of this energy act, into the underground caverns that function as oil storages in Shetland. This is because the grotesque is of a universal quality: it “can merge with various natural phenomena, with mountains, rivers, seas, islands, and continents. It can fill the entire universe.”42 The Loch Ness monster, with its long neck and antennae and horns, reaches far out into the cosmos, and lives simultaneously in the liminal, underground spaces that Bakhtin describes, and even calls them its home. The Loch Ness monster is therefore the epitome of Bakhtin’s environmental description of the grotesque.

40 William G. Doty, Mythography: The Study of Myths and Rituals (Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1986), 16-17.

41 Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, 318-319.

42 Ibid., 318.

Up Helly Aa act Ness Monstrosities, mask-on picture, 1976. Photo: the Up Helly Aa Committee Archives

Up Helly Aa act Ness Monstrosities, mask-off picture, 1976. Photo: the Up Helly Aa Committee Archives

What I wanted to showcase by discussing these energy acts is how they function as a creative form of communication and, at the same time, represent a subtle form of rebellion against oil. Certainly not every Shetlander would agree that they had political intentions with their acts. Yet these performances about oil production were always directed at discourse, as Up Helly Aa provided “a special type of communication impossible in everyday life.”43 The festival gave an annual chance to signal that nothing goes unnoticed in a small island community and functioned, to a certain degree, as “a world inside out”44 of “business as usual” on the Shetlands, criticizing and discussing oil in their own, fantastical ways.

In line with Bakhtin’s ideas is also the way that the “artfulness” in these energy acts can only be grasped when perceiving them as a kind of communication. The aesthetics in the acts come entirely from the wish of communicating a certain set of values from the Shetlanders’ perspective, in light of and reflexive to global outside pressures and influences. Thus, the line between what Bakhtin terms “art” and “life” in these acts is paper-thin.45 More specifically, the artistic mediums of performance and theatre were utilized to unravel the impotency – rather than the power – of a state apparatus heavily entangled with the oil industry.46 This conclusion is in line with historian Callum G. Brown’s interpretation of Up Helly Aa as a participatory event leading on from its historical tradition of “cocking a snook”47 at island authority by “fighting government officials for fun.”48

The role that the UHA participants took upon themselves in the island community was that of what sociologist Karl Mannheim termed the intelligentsia. This term is described in Bakhtin’s book as a “social group whose special task it is to provide an interpretation of the world for that society.”49 The guizers subsequently used their acts to translate oil developments to their island community on their own terms. Through the energy acts, it thus becomes possible to think anew about the actors and authors involved in the shaping of energy discourse. On themselves, the series of energy acts function as an archive of oil in their own rights, providing future generations with an aesthetic image of oil’s first decade on the islands.

The frivolous energy acts spark a series of more serious questions that apply not only to the local dimensions of oil production in Shetland but also to broader energy discourse happening around the world: Where is energy discourse shaped and by whom? How can people in small island communities use their creative culture to review and criticize oil and other energy production that bring new power structures to their direct living environments?5 And how can carnival, performance, and theatre transform power structures from the bottom up – if only by illustrating what happens when “Miss Piggy gets stuck in a pipeline”?

43 Ibid., 10.

44 Ibid., 11.

45 Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, viii.

46 Brown, Up-Helly-Aa, 77.

47 Ibid., 80.

48 Ibid., 90-92.

49 Karl Mannheim in Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, xii.

50 In Norway, revy is a popular local art form that is very similar to the nature of the UHA acts. The name revy comes from the French word revue, meaning “review” (in this case, a review of the previous year). To what extent such revues have been used to respond to oil and other energy developments in island communities needs further study, however.

Anachronistic Anarchist (user). “Shell advert 1975.” YouTube. Accessed 8 October 2024. Source: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JTKmoJoXDrM

Attorp, Adrienne, Sean Heron, and Ruth McAreavey. “Sustainable Rural Communities and Patriarchal Structures: The Case of Shetland’s Lerwick up-Helly-Aa.” In Rural Governance in the UK, edited by Hannah Budge and Sally Shortall. London: Routledge, 2022. DOI: 0.4324/9781003200208-10.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984.

Baldacchino, Godfrey. “Islands as Novelty Sites.” In Geographical Review, April (2010),165-172. DOI: 10.1111/j.1931-0846.2007.tb00396.x

Banks, Ken. “Women and Girls Make History at Up Helly Aa Fire Festival.” BBC News. 31 January 2024. URL: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c29klnxyk06o.

BBC News Office. “Rosebank Oil Field: What is the Row Over the Project?” BBC News. 27 September 2023. URL: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-66933832.

Bearman, Nick. “Scotland’s Most Remote Islands Don’t Want to Be in ‘Inset Maps’ Any More.” The Conversation. 6 November 2018. URL: https://theconversation.com/scotlands-most-remote-islands-dont-want-to-be-in-inset-maps-any-more-106139.

Bindersbee (user). “Pigs Cleaning Aqueduct” Wikicommons. Uploaded: 29 December 2010 to Public Domain. URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Pigging#/media/File:Pigs_cleaning_aqueduct.jpg.

Brown, Callum G. Up-Helly-Aa: Custom, Culture and Community in Shetland. Manchester: Mandolin Press, 1998.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. “Provincializing Europe: Postcoloniality and the Critique of History.” In Cultural Studies, Volume 6 (1992), Issue 3: 337-357. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09502389200490221

Civico, Adam. “What Happens on Lerwick Up Helly Aa Day?” Shetland.org. Accessed 8 October 2024. URL: https://www.shetland.org/blog/what-happens-lerwick-up-helly-aa.

Cope, Chris. “Forty Years and Counting for Oil at Sullom Voe.” Shetland News. 23 November 2018. URL: https://www.shetnews.co.uk/2018/11/23/forty-years-and-counting-for-oil-at-sullom-voe/.

Dy, Kiki. “Mythology and Misogyny at the Edge of the World” in The Sunday Long Read, (2022). https://sundaylongread.com/2023/07/26/mythology-and-misogyny-at-the-edge-of-the-world/.

EnQuest PLC. “Sullom Voe Oil Terminal.” EnQuest.com. March 2019. URL: https://www.enquest.com/fileadmin/content/operations/ICOP_PDFs/EnQ_ICOP_Sullom_Voe_Terminal_2019_03_28.pdf.

Finkel, Rebecca. “‘Dancing around the Ring of Fire’: Social Capital, Tourism Resistance, and Gender Dichotomies at up Helly Aa in Lerwick, Shetland.” Event Management 14, No. 4 (December 2010): 275-85.

Hill, Archie E., Carole L. Seyfrit, and Mona J. E. Danner. “Oil Development and Social Change in the Shetland Islands 1971-1991.” In Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 16, no. 1 (1998), 15-25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.1998.10590183.

Johnson, Karl and Up Helly Aa For Aa, “Fuel For the Fire: Tradition and Gender Controversy in Lerwick’s Up Helly Aa.” In Scottish Affairs 28.4 (2019): 459-474. DOI: 10.3366/scot.2019.0298.

Kiernan, Kat. “The Loch Ness Monster Turns 83: The Story of the Surgeons Photograph.” 19 April 2017. URL: https://www.donttakepictures.com/dtp-blog/2017/4/19/the-loch-ness-monster-turns-83-the-story-of-the-surgeons-photograph.

Mannheim, Karl. Ideology and Utopia. First Published in 1929. Republished: London and New York: Routledge, 1991.

Mitchell, James. “Participation in a Small Archipelago: The Shetland Negotiations.” In Regulation of Extractive Industries: Community Engagement in the Arctic, edited by Rachel Lorna Johnstone and Anne Merrild Hansen, 225-42. London and New York: Routledge, 2020.

Napier, Ian. Shetland’s Maritime Economy. Shetland: UHI, April 2022. URL: https://www.shetland.uhi.ac.uk/t4-media/one-web/uhi-shetland-images-and-documents/research/statistics/economy/Shetlands-Maritime-Economy-2022-04.pdf.

Newspaper advertisement on Oil in Shetland (p. 16) in The Shetland Times edition of 3 February 1978, Accessed in the Shetland Archives in Lerwick, UK, 24 January 2024.

Nicholson, James R. The Island Series: Shetland. Exeter: David and Charles, 1972.

Nicholson, James R. Shetland and Oil. London: William Luscombe Publisher Limited, 1975.

Promote Shetland. “Up Helly Aa Fire Festivals.” Shetland.org. Accessed 8 October 2024, URL: https://www.shetland.org/visit/do/up-helly-aa-fire-festivals.

RainbowSilver2ndBackup (user). “File: Timeline of the Introduction of Colour Television by Decade.svg.” Wikimedia Commons. Accessed 8 October 2024. URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Timeline_of_the_introduction_of_colour_television_by_decade.svg

Riddell, Neil. “Fishermen Round on Total over Pipeline Dangers.” Shetnews, 9 February 2016. URL: https://www.shetnews.co.uk/2016/02/09/fishermen-round-on-total-over-pipeline-dangers/.

Sandoval Chela, and Guisela Latorre. “Chicana/o Artivism: Judy Baca’s Digital Work with Youth of Color.” In Learning Race and Ethnicity: Youth and Digital Media, edited by Anna Everett. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, (2008), 81-108. DOI: 10.1162/dmal.9780262550673.081

Schneegans, Heinrich. Geschichte Der Grotesken Satire. First published in 1894. Republished: Whitefish, Montana (US), Kessinger Publishing, 2010.

Scott, Sir Peter and Robert Rines. “Naming the Loch Ness Monster.” In Nature 258 (1975): 466-468. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/258466a0.

Smith, Brian. “Up-Helly-Aa: Separating the Facts from the Fiction.” Shetland Times, 22 January 1993.

Stewart, Susan. “The Pickpocket: A Study in Tradition and Allusion.” In MLN, Vol. 95, No. 5, Comparative Literature (Dec., 1980), pp. 1127-1154. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2906486.

Tet Zoo. “The 1972 Loch Ness Monster Flipper Photos.” Accessed 8 October 2024. URL: https://tetzoo.com/blog/2020/8/17/loch-ness-monster-flipper-photos

The Ministry of Energy and the Norwegian Offshore Directorate. “Norway’s Petroleum History.” Norwegianpetroleum.no. Accessed 8 October 2024. URL: https://www.norskpetroleum.no/en/framework/norways-petroleum-history/#:~:text=Just%20before%20Christmas%20in%201969,started%20on%2015%20June%20197

The Shetland Times, edition of 2 February 1979. Accessed in the Shetland Archives in Lerwick, UK, 24 January 2024.

The Shetland Times reporter. “What the Squads Did and How They Looked.” Shetland Times. 3 February 1978, accessed in the Shetland Archives in Lerwick, UK, 25 January 2024.

The Shetland Times reporter. “What the Squads Did and How They Looked.” Shetland Times. 2 February 1979, accessed in the Shetland Archives in Lerwick, UK, 24 January 2024.

The Shetland Times reporter. “What the Squads Did and How They Looked.” Shetland Times, 30 January 1976. Accessed in the Shetland Archives in Lerwick, UK, 26 January 2024.

Up Helly Aa Committee. “Guizer Jarl and Jarl Squad.” uphellyaa.org. Accessed 8 October 2024, URL: https://www.uphellyaa.org/about-up-helly-aa/jarl-squad/

Up Helly Aa Committee. “Mask-On/ Mask-Off Pictures Archive.” The Galley Shed, Lerwick, Shetland, UK. Accessed 28 January 2023.

Watts, Laura. Energy at the End of the World: An Orkney Island Saga. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2024.

Miriam Sentler, “How to Act on Oil,” Metode (2025), vol. 3 ‘Currents’

I believe that laughing at the machinations of capitalist industrialists can still help raise people's awareness.

- Gusztáv Hámos

Act and act. Great slippages here. How is energy discourse shaped? Relationship between top and bottom? Policy makers and local community? Where does energy discourse happen? You subvert our expectations in your essay. What would your theory look like if it organically rose from the material itself?

- Victoria Bugge Øye

The text meaningfully pulls apart that crucial moment where a self-sufficient culture begins to fall apart.

- Ian Callender