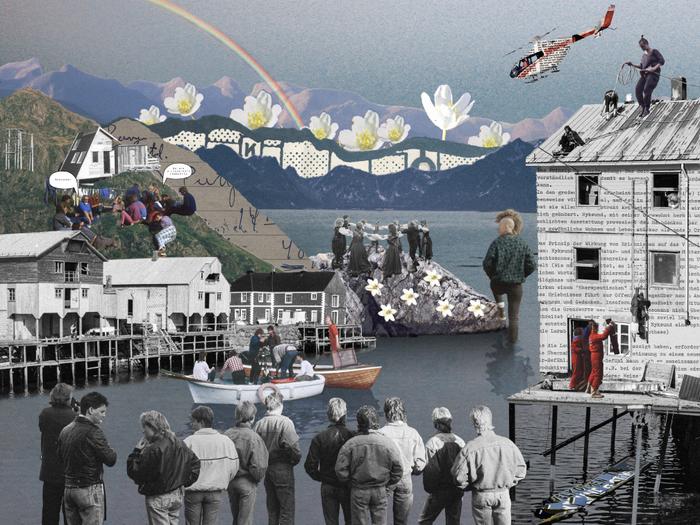

Collage and animation by Iryna Kliui and Katja Pratschke.

Collage and animation by Iryna Kliui and Katja Pratschke.

The core of utopia is the desire for being otherwise,

individually and collectively, subjectively and objectively.

(Ruth Levitas)1

One man’s treasure is another man’s trash.

(Guy Clarke)

1 Ruth Levitas, Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society, p. xi, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

There is a box in the middle of the room. Unsorted, abandoned, neglected. There is a box. A card-board box, collapsing from the weight of time. Of paper. Of folders. Colours fading. Structure collapsing. In the attic. There is a box. What a treasure.

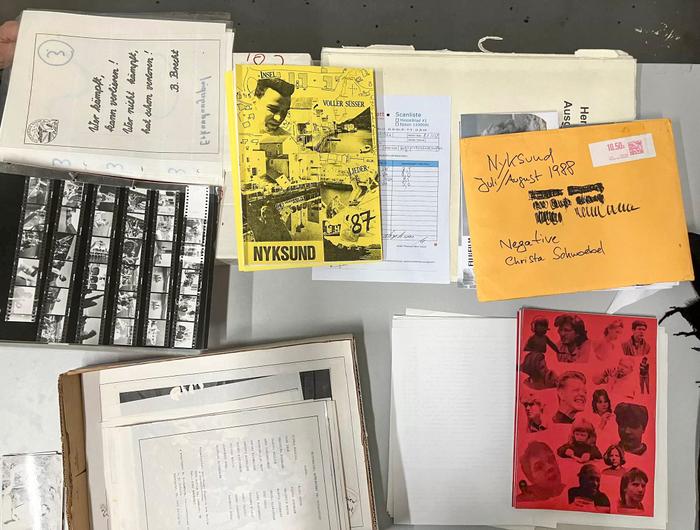

From the box we pull papers, shopping lists, photos, news clippings, reports, evaluations, jury mentions, and funding applications, manifests and project plans, technical drawings, and pedagogic visions. Dead matter? Passive materials? Not at all. To us, they are radiant signals, charged with utopian desires.

To us – an artist collective initiated by Katja, Elisabeth, and Gusztáv – this box is both a real physical object found in an attic in Germany as well as a figurative nexus of connection. Two of us are based in Berlin, one in Oslo. Our origins span Northern Norway, Budapest, and Frankfurt am Main. Two of us lived in Berlin when the Wall fell. Our origins matter, informing our search as we dig through the materials. What started as a handful of documents has grown into an evolving archive, with boxes and tapes now piling up in Katja’s and Gusztáv’s home in Berlin. We have become “accidental archivists”,2 increasingly getting access to a scattered legacy no institution previously had taken care of. Our archival project is accidental in the sense that none of us are archivists by education. We enter into archiving where institutions fall short.

2

Photo taken by Harald Sommer, 1986.

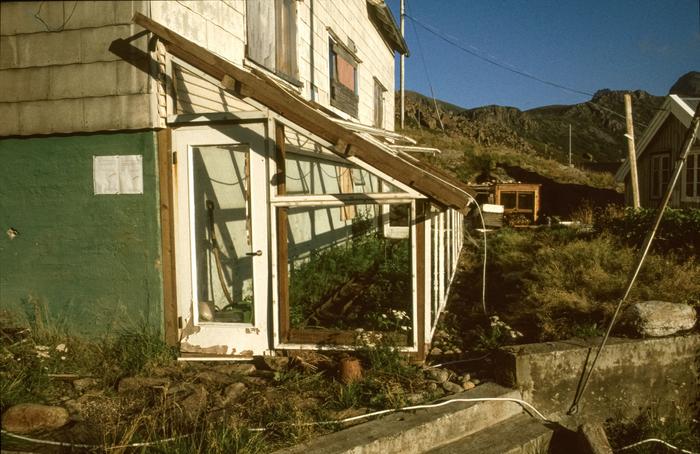

The content of the box is connected to an forgotten, ecotopian project that took place in a formerly thriving fishing village in Northern Norway in the 1980s. Abandoned in the 1960s and 1970s due to centralization politics and technological developments in the fishing industry, Nyksund became a void – a ghost town lending itself to reimaginings of diverse possible futures. It was here that the International Nyksund Project (INP, 1984–1992) unfolded, initiated by a group of scholars from West Berlin’s Technische Universität (TU). A traveller from West Berlin discovered the isolated ghost town, and by word of mouth, the currents of interpersonal information reaching a party in Cold War West Berlin, the fascination sparked a fire and a desire in TU’s social-pedagogical community.3 The potential space4 of opportunity in Nyksund resonated with emerging eco-political ideas, radical social pedagogics, and practices of environmental engineering at the school. The first group of instructors and students from TU left the smog and the isolated state of West Berlin in the early 1980s and travelled to the vast vistas of Nyksund, with a green light from the local municipality of Øksnes and its administration.

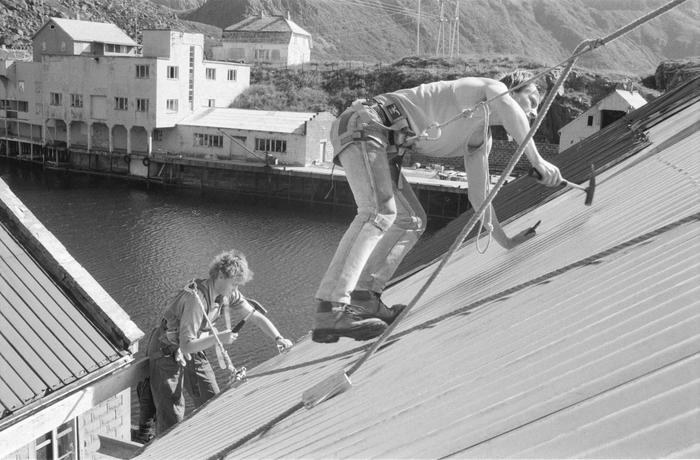

For the West Berliners, Nyksund was the perfect starting point. The place and its buildings were charged with meaning and heritage, yet left to crumble. All infrastructure had been shut down. The group repaired roofs, built solar-cell showers, installed windmills, and created biogas electricity generators – sustainable innovations that were ahead of their time.5 They approached the place with care for its history, yet envisioned Nyksund as a sustainable International Youth City, a place where young people could build an eco-friendly community and take agency over their futures. Between 1984 and 1992, more than 3,000 participants from across Europe joined this interdisciplinary experiment, driven by radical pedagogies and eco-critical and utopian ideals. The project won the EU’s first European Environmental Award in the Cultural Heritage category. It was ahead of its time – it was a model project.6

3 Interview with Burkhard Herrmann, leader of the INP, August 2022.

4 Donald Woods Winnicott, Playing and Reality, Psychology Press, 1971/1991.

5 Grethe Andreassen, En annen verden, Orkana Forlag, 2017.

6 Jury statement, Europäischer Umweltpreis, Bonn, 1988.

In some ways, the INP project was unsuccessful. It ended. Its goal was not achieved. Its documentation is not taken care of by its initiating institution. And thus its scattered archival materials, which have now been donated to us, bear witness to a closed event that happened at a certain place at a certain time. However, if one explores the INP’s materials through the lens of Ruth Levitas’ concept of “Utopia as method”, the legacy of the International Nyksund Project becomes active – it is not no longer a failed dream but a source of vital and generative signals, relevant for addressing contemporary and future challenges.

Photo taken by Katja Pratschke, scanning documents, collection Wolfgang Eschenhorn.

Levitas argues that Utopia is useful for our 21-century crises and should be understood primarily not as an end result, but as a reflexive, dialogical, and provisional method through which the alternatively possible / possible futures can be explored and made visible.7 Utopias are in this sense not first and foremost complete imagined worlds, or a “non-place” as its Greek roots indicates, but desires – the aspirations for a transformed existence that runs like currents or ethical signals through space and time, manifested through materials and diverse artistic, societal, and cultural practices. Such utopian desires, Levitas notes, are grounded in a lack, or a want – in a sense that something is missing.8 Everything that helps in fulfilling this want, or in probing the alternatively possible, is then utopian, and thus utopian desires become embedded in various materials, such as archival materials and buildings. A box with photographs and documents becomes radiant and charged with aspirations.

In 1983 Nyksund became a meeting place for diverse signals converging in space and time. These signals originated from diverse communities, locally and internationally – from Berlin, from Northern Norway, from other corners of Europe. It was the era of the Cold War, eco-socialist movements were on the rise, and traces of these activities and the ideals of desired futures can be found in the documents from the International Nyksund Project: images, videos, brochures, shopping lists, mind maps, games, collages, manifestos, and so forth. Through these documents, the ideas, the everyday life, the struggles, and the victories of this project run like signals – currents that can be received, reactivated, and re-transmitted.

How did these agencies interact – resonate or conflict? How did the ethical signals and utopian desires of the INP manifest in their activities and creations? Which signals faded? Which remained strong? What did the local community receive and retransmit? How can we recover signals that “fell to the ground”, strengthen them, and pass them on? How can we, as artists and scholars, receive and transmit signals for future gain?

As accidental archivists, we approach the archive not as a static repository but as a dynamic field of possibilities.

7 Ruth Levitas, Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

8 Ruth Levitas, Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Collage and animation by Iryna Kliui and Katja Pratschke.

In the box there is a report – a black-and-white booklet, depicting the fish storage buildings in decay, wooden decks you can fall through.

Nyksundutredningen [The Nyksund Report]9 was initiated in 1976, after Nyksund had been completely abandoned since 1975, becoming a symbol of the structural changes affecting Northern Norwegian coastal areas at the time: centralization, welfare and urbanization policies, and the industrialization of fisheries. The report was commissioned by Øksnes municipality, where certain voices in local politics called for the preservation of Nyksund.

9 Erik Alfstad, K.O., Ericsson, W.G. Finnes, A. Hansen, T. Larsen, T. Lundevall, K. Rørvik, and I. Toften, Nyksundutredningen, Nordland Boktrykkeri, 1978.

The place received attention from the press already at the time. There was something about it: its cultural history, as one of the largest fishing villages in the region, suddenly gone quiet; its architectural and topographical characteristics, with tall buildings crammed together in a small area, facing the rough, open sea, with the mountains forming a “back wall” against the rest of the world – a place framed by two breakwaters, accessible only by boat or, hazardously, via a narrow road by car. The architect Tarald Lundevall, in a master’s thesis interview, highlights two unique aspects of Nyksund: the place’s architectural density and urbanity: “I have examined several fishing villages along the coast. There is no fishing village with as high a level of architectural density as Nyksund.”10

Nyksund, with its broad preservation needs, inspired the formation of a multidisciplinary task force at the county level, consisting of architects, conservators, bureaucrats, and administrators of tourism and culture. Their mission was to map and analyse Nyksund’s resources and potential. In 1977 – two master’s students from the University of Tromsø, Kjell Arne Rørvik and Trond Larsen, were tasked with writing the report. A local Nyksund group was subsequently established, including the architect Lundevall, the local Nyksund inhabitant Bodil Kristoffersen, and the historian Ivar Toften.11 Together, they drafted the Nyksund Report, and the local desire to preserve the place is notably present in its pages: a want to ensure that the “death” of the formerly thriving fishing village does not decay into a loss of memory, identity, or sense of “who we are”.

The report also signals a desire to probe future possibilities – a willingness to adapt and rethink. The report is grounded in desires that are multileveled. First, there is the desire to “preserve Nyksund at least between two book covers” through a technical, architectural, cultural, and historical description of the place. The investigations are highlighted as works of documentation that will have their own value regardless of the destiny of the place. Second, there is the need to evaluate Nyksund for future use: A site for tourism? An artists’ hub? A youth and research camp? A museum? A new business? A vacation site? These are suggestions that are all in the report, as reports within the report that detail a possible action plan for the site. And third, there is the need for a model report for similar future projects, as “the report is related to a situation that is not unusual in the region – abandoned fishing villages with culturally and historically interesting buildings”,12 as the quote from the Norwegian Environmental Directorate states.

10 Tarald Lundevall, in B.M. Petttersen, Nyksund – the place that refused to die, Nord Universitet, 2013, p. 42.

11 Lundevall would later become one of the “fathers” of the new Oslo Opera House. At the time of the report, he lived in Øksnes, as part of his early training as an architect.

12 Erik Alfstad, K.O., Ericsson, W.G. Finnes, A. Hansen, T. Larsen, T. Lundevall, K. Rørvik, and I. Toften, Nyksundutredningen, Nordland Boktrykkeri, 1978 p. 7.

The journey from West Berlin to Nyksund, around 2700 km, was organized by bus. The starting point was West Berlin in the 1980s, not a natural island like Nyksund, not surrounded by the sea, but an artificial one, enclosed by the Berlin Wall, “for years a kind of intellectual laboratory in which utopias flourished, and lifestyles were tested”.13 Road travel required transit through East Germany, before continuing up through Scandinavia:

“Kilometre by kilometre, five hours, ten hours, one day, one night, still a long way from our destination. Outside, the landscape is changing: we’re heading north, inside all the faces are still strangers. Pictures in my mind are like mute images, flat photos. How am I supposed to sit, my arms, my legs, my back and whatever else is left of me, everything hurts, then the first gymnastic exercises through the bus, double-header rounds, people run out of those photos, we talk and laugh.”14

13 “Die Insel West-Berlin” (The West Berlin Island), Zeitschrift für Ideengeschichte, vol. 2 no. 4, Winter 2008, p. 4.

14 From 1986 to 1989, the educator Wolfgang Eschenhorn travelled to Nyksund with young participants from the Neukölln district in West Berlin. The Broschüre 1987 was written and designed by participants, educators, and teaching students after the Nyksund experience at the Wannseeheim Berlin.

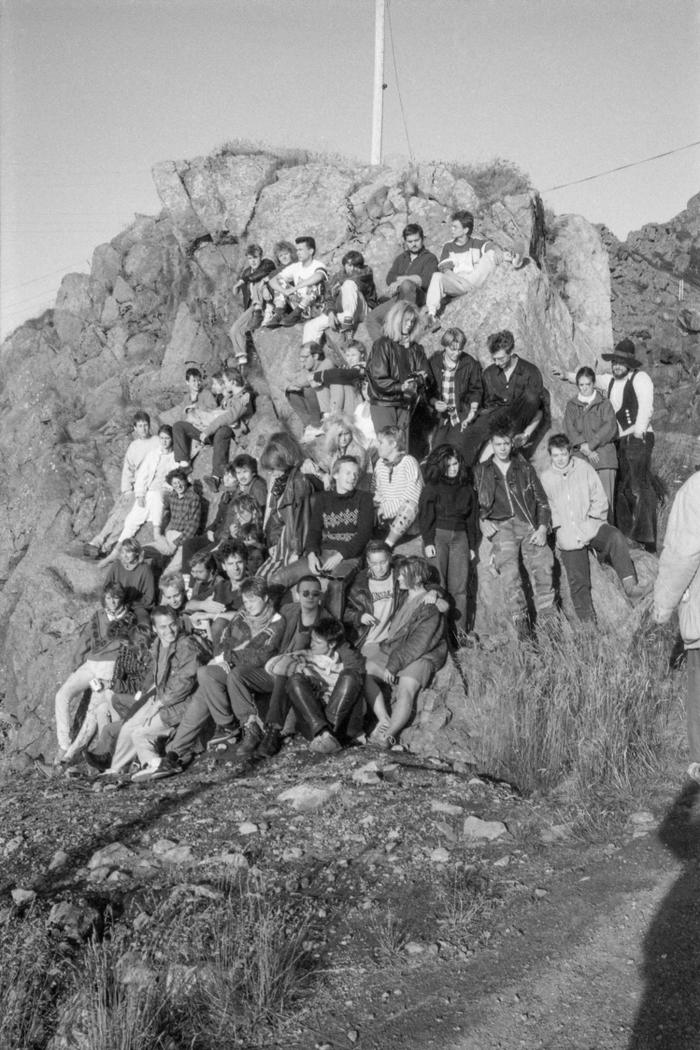

Group image, photo for the back cover of the 1987 brochure. Collection: Wolfgang Eschenhorn.

The travel group consisted of young people and students. Their common destination: The repair of the abandoned fishing village NYKSUND. They embarked on an educational-ecological experiment. In 1985, students of social pedagogy, environmental engineering, and architecture responded to a call for participation in a theory-practice seminar at Faculty 22 (Educational Science with a focus on Social Pedagogy) at the Technical University West Berlin. After a long process of searching for the “third common cause”,15 they agreed on “unemployed young people and young people at risk of unemployment” as the target group.

Gunther Soukup, who as a professor accompanied three two-year Nyksund theory-practice seminars from 1984 to 1990, writes on the motives of the students: “It happened at the time that Berlin students occupied the houses that were empty for the purpose of speculation and made them habitable again. They called this ‘repair squatting’. For many of them, this was the first chance to experience themselves as being productive and creative. A new city government [in West Berlin] ended the group’s useful activities with police violence. As a result, many students sought to apply their newly acquired knowledge elsewhere, even if it was in the far north.”16

15 In Bertolt Brecht’s play “The Mother”, first performed in Berlin in 1932, the mother of the Russian revolutionary Pavel recites the “Praise of the Third Cause”. Brecht had already encountered the word during his studies of Marxist writings; the term was a fixed terminological component of the German labour movement. Engels spoke of “serving our common cause”.

16 Gunther Soukup, “Das Abseits und das Gewöhnliche. Nyksund als Chance der Verfremdung” (The Offside and the Ordinary. Nyksund as an opportunity for estrangement), in: C. Wolfgang Müller and Winfried Ripp (Ed), Tropfen auf dem heißen Stein. 25 Jahre Institut für Sozialpädagogik der TU Berlin, Beltz Verlag, 1992, p. 192 ff.

Photo taken by Carsten Lüring, 1984.

The parents of the young people travelling to Nyksund were certainly not among the intellectuals who were trying out alternative counter-worlds. Their kids were part of the “youth crisis” that was emerging in the cities of postmodern industrial societies. “Nyksund as a place of estrangement”17 offered answers to loss or absence of concrete experiences or immediacy, of a sense of belonging, of shapable environments and social visions for future societies and individual perspectives.

The Nyksund experience changed the young people. Nyksund left an impression. And they returned: “Being there again, immersing myself in the hustle and bustle of village life, in the light, the mountains. Just as unimaginable, far away, and unreal as it was for me here in Berlin, my normal life now disappears behind the intensity of these impressions.”18

17 See Signal 6, “Deviating from the ‘Normal’”.

18 Material Wolfgang Eschenhorn, Brochure 1987, written and designed by participants, educators and teaching students.

In the 1980s, concerns about alcohol consumption in local youth culture surfaced in the local newspaper Bladet Vesterålen.19 An increase in driving-off-the-road accidents was linked to reckless driving and party culture. In the following years, youth work in the region became an increasing priority.20 Efforts were made to offer creative activities, not just discotheques, to prevent young people from hanging out on the streets. Municipalities and private businesses invested in sports halls and football fields. Leaders of youth clubs were trained through local seminars. The goal was to enable young people to activate themselves, discover their resources, and take responsibility, addressing a reported lack of contact with grown-ups apart from authorities.

However, the experience of being young in Øksnes municipality varied widely. Apart from school, it could mean doing sports like skiing, swimming, volleyball, football, or handball. It could mean going to the youth club, partying, playing in a marching band, drinking, hanging out with friends along the main street in Myre, driving around with older boys. The long distances between places fuelled a car culture, where older boys gained status and independence through their vehicles. It could mean having a part in the local theatre group in the neighbouring place of Alsvåg. Or it could mean participating in church activities. It all depended on which village you lived in, your family background, and the resources in your local community.

19 Bladet Vesterålen, “Ungdomsulykkene på vegene. En følge av ungdomskulturen”. October 14 1980, the National Library of Norway’s archives.

20 Bladet Vesterålen, “Ungdomsklubbene viktige i forebyggende arbeid”, 25 October 1983, p. 2, the National Library of Norway’s archives.

Photo taken by Gunther Soukup, collection Renate Wendland-Soukup, 1985.

Anne Beate Hovind, today known as an urban developer curating and producing art in public spaces,21 was then a teacher and youth worker from Oslo and part of the Nyksund support group in Oslo.22 At that time she worked in the Øksnes municipality to raise awareness about contraception: “A particular challenge was the lack of girls aged 16–18. They left to get an education, while the boys stayed behind, eager to go fishing. They dreamed of making big money. But their staying in the community put significant pressure on the 14-year-old girls.”23 This led to a risk of unwanted pregnancies, she says. Hovind and a group of youth workers introduced the magazine SMASK to local kids.24 SMASK was rather innocent and carefully developed. However, the group faced considerable local resistance. Attitudes towards talking about sex and contraception were conservative compared to cities further south. Hovind and her team, as well as the magazine, were criticized by the social authorities in Øksnes for encouraging immoral behaviour, and the magazine was withheld from libraries and youth clubs.

At this time, the abandoned village of Nyksund became a place for adventure – and lashing out. Some young people went on weekend raids to Nyksund, where furniture, machines, hand-painted coffins, and cutlery were among the things left behind. It was broadly accepted that one could take whatever was left in Nyksund.25 Young and old took what their hearts desired. Some channelled their frustration or sense of mischief by setting something on fire, or smashing the windows of abandoned houses. Others brought their partners for romantic walks around the ghost town. Grethe Andreassen was a teenager in the early 1980s working in the INP as a communications manager. In her book about the International Nyksund Project, Andreassen describes the situation: “The place had turned into a no-man’s-land, where the rules that applied in the rest of society no longer held sway.”26

Nyksund was out of view, out of control.

21 Her most notable projects are the Future Library and Losæter, integrating art, community, and sustainability into urban landscapes.

22 Anne Beate Hovind joined the support group in Oslo for the INP after a year as a teacher and youth worker in Øksnes. Hovind helped with writing applications and engaging with society at large. E-mail conversation with Elisabeth Brun, 20 December 2024.

23 Anne Beate Hovind, e-mail conversation with Elisabeth Brun, 20 December 2024.

24 SMASK translates as “MWAH” or “SMACK”, which is the sound of a kiss. The magazine was published by a national association for youth clubs (Fritidsklubbenes Landsforbund).

25 Grethe Andreassen, En annen verden, Orkana Forlag, 2017.

26 Ibid, p. 16.

Photo: Harald Sommer, 1986.

“What should, what can become of Nyksund?

Geo-ecological centre; geo-ecological village; eco-village for workshops, seminars, with a soft energy park; centre for ecology and testing of alternative technologies; Ecopark Arctic; eco-show à la Wales; a place for experimental projects in the field of ecology (perhaps a research station); a biotope to create new life in the village, taking ecological aspects into account.”27 These ecological visions for alternative futures of the village have been written down on cards by students, educators, members of QuaBS,28 and members of Nordlicht e.V.29 that attended a closed meeting in November 1987 in Buchholz, West Germany.

After Phase 1, the rescue of a culturally and historically significant site with the participation of young people, including the long-term unemployed, and the start of Phase 2, the construction of a youth education and meeting centre, many Nyksund project activities took into account the transmission of a new understanding of the environment. This included raising awareness of environmentally friendly solutions to problems, the re-testing of forgotten techniques and methods of craftsmanship, and raising awareness of “wrong” lifestyles such as unhealthy food, isolation, and too much consumerism in the large urban centres. The project explored new ways of life in the periphery, restoring the connection between the consumption of food and its production or procurement: fishing, vegetable growing, mushroom and berry picking, and baking bread.30

27 Protocol written and signed by Susanne Kretschmer, Nyksund closed meeting, 29 October–1 November 1987, in the Tagungshaus Alte Schule, Buchholz, p. 16.

28 Qualifizierungsvereinigung Berliner Sozialpädagoginnen und Sozialpädagogen e.V. (Qualification Association of Berlin Social Pedagogues).

29 Nordlicht translates as “northern lights”.

30 Quote from part 2 of a document, whose cover is missing the title “2. The dimensions of the Nyksund project”, p. 4, presumably from 1985. Part 2 describes the three project phases that were planned.

Photos: Harald Sommer, setting up a windmill, 1986.

Photos: Harald Sommer, setting up a windmill, 1986.

Photo: Carsten Lüring, 1988.

Photo: Carsten Lüring, 1988.

The educational objectives are described in the concept paper “Nyksund, a Place of Environmental Education”31 as a “large-scale attempt to reform life and living in the metropolises through estrangement and alternative experience”, impulses picked up from the alternative movement from the seventies. Numerous alternative forms of co-living and co-working were practiced in West Berlin at that time, from the eco-bakery to the cooperative, the alternative newspaper to the eco-travel agency. A wave of project start-ups was triggered by the TUNIX32 congress that took place at the Technical University of West Berlin in 1978. Spontis33 and Autonomes discussed exits from society and developed counter-models. “Because the big utopias had failed, the left relied on the politics of small steps.”34 The largest left-wing intellectual event since the beginning of the student movement, with around 15,000 participants, did not seek to overthrow existing systems, but to put alternatives into action and establish countercultures.

31 “Das Nyksund-Projekt als Ort der Umwelterziehung”, 4-page-long document, with a stamp of Nordlicht e.V.. The association was founded to offer activities and structures to young people for the time after the Nyksund stay in Berlin.

32 Tunix (“Do nothing”), https://taz.de/40-Jahre-Tunix-Kongress-in-West-Berlin/!5478617/

33 The Spontis (from spontaneous) was a left-wing movement whose members included Joschka Fischer and Daniel Cohn-Bendit.

34 “The Tunix-Congress 1978: New dreams instead of world revolution”, in: https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/der-tunix-kongress-1978-neue-traeume-statt-weltrevolution-100.html

Photo: Carsten Lüring, 1985.

In the harbour of Nyksund a building stands out: a modernistic green cube called the Freezer (Fryseriet), a three-storey-high concrete construction, contrasting the more traditional fish storage buildings nearby. The building, built in the 1940/50s, signals a future-oriented optimism, a will to create prosperity in this place.

Motivated by the era’s economic crisis, the social democratic leadership wanted to ensure employment and welfare for all. Backed by fishermen and farmers, the Labour Party, which came into power in 1935, planned 56 new cold storage facilities in Norway for exporting frozen fish products – a plan that historian Bjørn Petter Finstad labelled a “true-born child of social democracy”.35

The local frozen fish industry had a breakthrough moment during World War II, fuelled by German wartime capital.36 The vision of a “Greater Germanic Reich” motivated a long-term planning in occupied territories, and in the nearby rural town of Melbu, German capital and new technology founded a large frozen fish factory (1943, later Lerøy). The efficient and well-organized German production system extended to Nyksund, where business flourished, and fish was delivered to Melbu, sparking the initiative to build a modern and innovative freezer in Nyksund. Trucks could drive onto the refrigerator’s flat roof to unload the fish into the freight elevator. You had the best view from the roof, as the numerous photos from the INP prove.

The Freezer thereby signals a process which also contributed to Nyksund’s abandonment and decline – a final tremble before shutting down. The post-war momentum of frozen fish sales was fuelled by national ambitions to rebuild Norway from the 1950s onwards. The rural areas of Northern Norway were industrialized, urbanized, and transformed into small rural-urban towns. The national and local desire for modernization, and better infrastructure, motivated a mass migration of families from Nyksund to the neighbouring urban town of Myre, which before the war was nothing more than a populated crossroad in the midst of moist marshland. Myre, with its sheltered natural harbour and connection to the national road, experienced rapid growth throughout the 1950s; Nyksund, with its shallow harbour and lack of road access, lost out.

The mass migration from Nyksund was not a forced process, some argue, but desired,37 one that was supported by state funds and administered by the local municipality. The Øksnes municipality was among the most eager in Norway to distribute these subsidies for “relocation”.38 People receiving subsidies had to sign an agreement that they were never to move back. Other sources emphasize it was by force in effect.39 National authorities designated Nyksund as an utvær and a place to be phased out. It is said that the road that people in Nyksund had fought for over so many years, was used as a road for emigration when it finally came.

NRK documentary, 197540

“Journalist: Why did you move to Myre?

Fisherman: Well, it ultimately became impossible to live here. ... We had kids who were going to school, and it was shut down. ... We had no other option; we had to move away from there.”

For the fisherman, there was sadness, a loss of place.

35 Bjørn-Petter Finstad, “Finotro: Statseidfiskeindustri i Finnmark og Nord-Troms. Fra plan til avvikling”, PhD diss., p. 5, University of Tromsø, 2005.

36 Karl Otto Ellefsen and Tarald Lundevall, North Atlantic Coast: A Monograph of Place, Pax Forlag, 2019.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 Grethe Andreassen, En annen verden, Orkana Forlag, 2017,. p. 14.

40 NRK, Fiske og jordbruk, er det fremtiden for Vesterålen?, documentary, NRK’s archives, 1975.

Two boxes with folders filled with documents, including a timetable with the heading “Norway theory-practice seminar – closed-door meeting in Zeetze”.41 On the second day, the programme focuses on “Nyksund and the V-Effect”. Did the students suggest topics and prepare the working materials on Bertolt Brecht, on “Epic Theatre and Alienation”, in order to develop their pedagogic concepts? Or did the teachers and pedagogues, among them members of QuaBS,42 socialized by left-wing workers’ youth associations and shaped by the protest movements of 1968, introduce Marx’s ideas?

Marx formulated the concept of alienated labour in the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844:

1 / The worker is confronted with the product of his labour as an alien being and an independent power. The product of his labour does not belong to him but to his employer.

2 / This work activity does not satisfy any other needs of the worker than the restoration of his labour power.

3 / An immediate consequence of the alienation of the product of his work activity and human nature is the alienation of man from man.

According to Marx, the alienated person accepts his social situation unconsciously, that is he is not aware of his alienation and therefore cannot free himself from his unfortunate situation by his own strength.

41 The closed meeting took place from 2 to 5 March 1986 in Zeetze, in Wendland, West Germany. Wendland is known for its anti-nuclear protests in 1980 against the construction of a nuclear waste dump. With the protest camp Republic of Free Wendland, activists occupied the territory destined for radioactive waste storage for 33 days.

42 Qualifizierungsvereinigung Berliner Sozialpädagoginnen und Sozialpädagogen e.V. (Qualification Association of Berlin Social Pedagogues)

Photos: Harald Sommer, on the roof of the Freezer, 1986.

Photos: Harald Sommer, on the roof of the Freezer, 1986.

Bertolt Brecht imagined and formulated it in his essay “Political Theory of Estrangement” that the “estranged” representation of the living situation of the proletariat would make their social and economic situation clear and thereby develop their class consciousness. This would develop the workers’ solidarity and promote their class consciousness, which would lead to the communist revolution that would culminate in the dictatorship of the proletariat. The so-called communist revolution in Russia in 1917 did not lead to the dictatorship of the proletariat, but to the dictatorship of Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin from January 1924. His personality cult, his totalitarianism, his fear-inducing mass surveillance, and his aggressive imperialism turned the Marxist hope into a failed utopia.

Nevertheless, the students succeeded in transferring Bertolt Brecht’s ideas of performative estrangement and defamiliarization into a contemporary form. The village of Nyksund, abandoned by fishermen, was perfectly suited for the implementation, given its location in the midst of barren nature with all the associated alienation and isolation factors. There, normal demands and expectations of comfort and luxury are deliberately disappointed and the everyday reality of big city life is defamiliarized. The Nyksund pedagogy is “applied estrangement”. By participating in a radically different way of life under radically different living conditions, the “normal” and apparently self-evident lifestyle appears questionable and in need of change.

“In 1985, Nyksund was still a ruin or ghost town with no prospects. Debris, scrap, and shards were everywhere, with sheep droppings and garbage in the houses. Nyksund, a place of desolation.” Chapter C 2.2. Konzeptionsdiskussion / Entwürfe, folder QuaBS e.V. Nyksund – Auswertung, page 22

Collage and animation by Iryna Kliui and Katja Pratschke.

Photos: Harald Sommer, 1986.

The photos taken by the INP participants from West Berlin, such as Harald Sommer and Carsten Lüring, are charged with fascination for the natural elements of the sub-Arctic north. The analogue photographs radiate with a playful interaction with light: fog, sunsets, backlit mountain tops, and sunbreaks at sea. The participants of the INP engage with elements in front of the camera: nude dips in marshland pits and placing odd objects in the moss. There is little bad weather in the photographs. The vistas are conspicuously held in awe.

These were also the elements that formed everyday life for Sámi and Norwegian locals who had lived there since before the Viking Age. For them, this was not merely a scenery but the source of food and life-saving knowledge: salting, icing, and drying fish, harvesting feathers, herding reindeer, and collecting berries. Farming in Nyksund was sparse due to the harsh weather, and the rocky headlands and bare islands invited hunting, gathering, and particularly fishing.43 In the late 1800s, Nyksund experienced prosperity from vast herring migrations, followed by cod passing just outside – “on the edge”, på egga – where the seabed steeply descends into the depths of the Norwegian Sea.44

At that time in the region, people’s relationship with the weather and the seasons was of course both intimate and all-important. Embodied knowledge was passed down through generations and taught from childhood, shaping a deep awareness of the environment. Has there been enough sun for the berries to ripen? Is the wind too strong for fishing? Changes in the environment were acutely felt across the entire food chain. Dramatic shifts could lead to poverty or even death. No wonder desires for welfare and social security began to emerge.

The INP participants, in their way, were also attuned to environmental concerns – pollution and ecological vulnerability were keywords. In a document titled Jahresprogramm 1987, they describe how a stay in Nyksund could foster an understanding of natural cycles and their fragility. They highlighted recent environmental disasters like Sandoz and Chernobyl, the dying forests of southern Norway, oxygen-deprived lakes, and the radioactive effects on sheep and reindeer. “The ozone layer above us is weakened, and the consequence of this will be a change in the Earth’s entire climate balance.”45 Where did these concerns originate? From personal encounters in West Berlin? From smog, a lack of clean air? A longing for the natural elements, for closeness to nature?

Elisabeth Brun, one of the authors of this text, was a kid in Øksnes in the early 1980s. At that time, it was still common for her and other local children to participate in berry picking, potato harvesting, and collective farming duties for the extended family. Meanwhile, traditional handcraft and domestic knowledge was undoubtedly in decline, following society’s structural changes. In the early 1980s, the urbanization of Myre and nearby villages, with their schools, businesses, and services, generated jobs.46 Communications technology was more equally distributed. Brun grew up in a village close to both Myre and Nyksund – in which many of her friends had parents working as teachers or civil servants. Supermarkets provided people with necessities. The welfare society was profoundly present in the region. For young people, sports, television entertainment, and hanging out dominated their spare time. Nature had once directly shaped life in the area, while people’s ties to fisheries and farming were significantly weakened. Still, Brun argues, there remained a sense of nature – a pace inherited – emerging through the daily contact with the elements. A potential, unleashed. An inheritance latent?

43 Halvard Toften, Historia om Øksnes-folket, Øksnes historielag, 2020; Johan I. Borgos, Samer ved Storhavet, Orkana Forlag, 2020.

44 Karl Otto Ellefsen and Tarald Lundevall, North Atlantic Coast: A Monograph of Place, Pax Forlag, 2019.

45 “Nyksund Jahresprogramm” (Nyksund Annual Programme), 1987, p. 8, collection Götz Berge.

46 Karl Otto Ellefsen and Tarald Lundevall, North Atlantic Coast: A Monograph of Place, Pax Forlag, 2019.

Photos of the 1988 European Environmental Award ceremony in Bonn with Burkhard Herrmann and Götz Berge, as well as letters, documents, and a certificate, are among the archive documents. “Nyksund is a world leader in applied environmental protection,” so the jury’s statement for First Prize in the Cultural Heritage category, awarded to the Nyksund Project. The “initiating” group, students of pedagogy that interacted with students of the newly founded department of environmental technology, coordinated their expectations, requirements, and skills into a concept that allowed a new environmental awareness to be transmitted to everybody participating at the project.

They picked up waves generated by environmental activists and the anti-nuclear movement that led to the founding of numerous environmental protection groups and initiatives, which merged into citizens’ initiatives and associations in the mid-1970s. In 1978, the Alternative List – For Democracy and Environmental Protection was founded in West Berlin and in early 1979 the Greens, who entered the German Parliament in 1983. These early associations established an awareness for environmental problems in the public and had a huge impact on environmental protection policy and laws in West Germany.

Photos: Carsten Lüring and Harald Sommer, solar-powered shower house, 1985-1988.

Photos: Carsten Lüring and Harald Sommer, solar-powered shower house, 1985-1988.

Photos: Carsten Lüring and Harald Sommer, solar-powered shower house, 1985-1988.

So how to integrate these signals for ecological awareness into the Nyksund project?

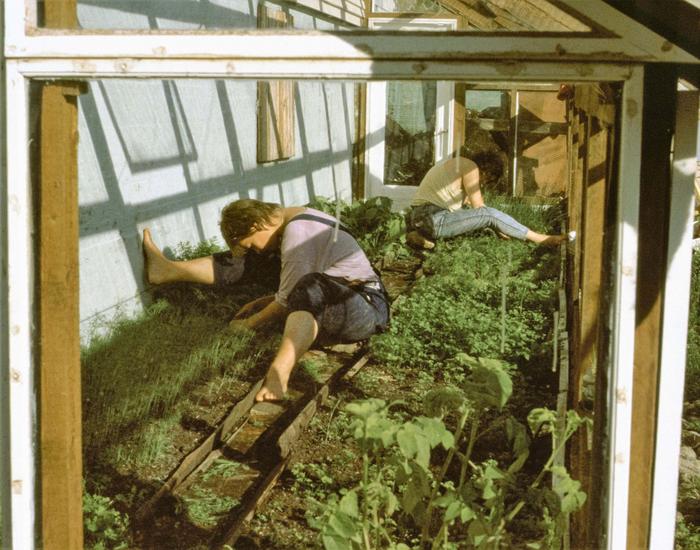

From the outset the renovation of buildings in Nyksund was carried out with ecological aspects in mind. The students of environmental technology joined the project with an interest in interdisciplinary work and the prospect of being able to carry out their project internships in Nyksund. The testing of environmental projects started with the building of a solar-powered shower house (1985), composting toilets and a lean-to greenhouse for growing vegetables for partial self-sufficiency (1986), and a biogas plant and, as part of an interdisciplinary energy seminar, a small wind turbine that provided light to one floor of a residential building (1987). “The village provides a testing ground for all these projects and time will tell which of these experimental projects can be expanded.”47

47 “Zusammenfassende Darstellung des Nyksund Projektes” (Summary Presentation of the Nyksund Project), chapter 3, “Das Ökologische Konzept – Beispiele aus der Praxis” (The Ecological Concept – Practical Examples), p. 6.

Photos taken by Carsten Lüring, inside design of the solar-powered shower house, 1985.

Photos taken by Carsten Lüring, inside design of the solar-powered shower house, 1985.

The students of pedagogy connected the environmental projects in an overall pedagogical concept, called “Nyksund as a Place of Environmental Education”,48 and developed environmental activities connected to the topics of food, cleaning, building materials, water disposal (sanitary facilities), and waste disposal. The young people who travelled to Nyksund for workshops were involved in all these aspects and were accompanied by educators who at the same time gained knowledge in the field of ecologically oriented social pedagogy.

The students were well aware that the continued existence of “the place depends on the environmental sensitivity of its young inhabitants”. Nyksund meant being in direct contact with nature. Ecological footprints could be experienced instantly. The eighteen rules on ecology, nutrition, and living together in Nyksund, which were developed by the students, served to communicate the reasons and contexts for environmentally friendly measures with the young participants.

48

Photos taken by Carsten Lüring, inside design of the solar-powered shower house, 1985.

Inside the box, there is a yellowed piece of paper – a news clipping from the local newspaper Lofotposten. It reads:

“In recent years, Nyksund has attracted a mixed crowd of visitors: punks and skinheads, the down-and-out and the highly privileged, simple craftsmen and hardened city types, eco-enthusiasts and fashionistas, political and apolitical, feminists and traditionalists, machos and softies – in short, every imaginable group of the younger generation.” – Lofotposten, November 198849

The article highlights in its text the shock that many Berlin youths experienced when they travel from the hustle and bustle of Berlin to the simple life of Nyksund. Yet its tone conveys a view from outside, an “us watching them”.

A local point of view.

Another document, a protocol of the closed door meeting 1987 in Buchholz, West Germany, with students of pedagogy, Gunter Soukup, Burkhard Herrmann, and QuaBS and Nordlicht members participating, expresses the INP’s desire for more contact with the local Norwegian youth. Strategies to embed the project in the local community are listed, including: 1) adding more Norwegians to the team, 2) establishing or strengthening contact with the youth centre in Myre (the youth club Skarven), and 3) attracting more Norwegian youth to Nyksund. So far, the protocol states, there has only been sporadic contact with Norwegians.

49 Lofotposten, “Sjokkopplevelse”, 19 Nov 1988, the National Library of Norway’s archives.

Photo taken by Gunther Soukup, fishing herring at the harbor of Nyksund with the “neighbors”, collection Renate Wendland-Soukup, 1985.

The protocol emphasizes a solution: developing a positive attitude towards so-called “tourists” and viewing them as an opportunity for contact with Norwegians. The term “tourists” refers to the “numerous Norwegian tourists” visiting Nyksund village on weekends. The students from Bodø and West Berlin (1985) organized a café service for them in order to provide information about the project. A volleyball net set up on the market square proved to be a “good initiative” to “easily” establish contact with local young people. Further initiatives are also described: “Neighbours help each other, contacts are made with Norwegian families who take in young people [from the INP project] as guests for a weekend.”50

The document states an ambition to help people discover, learn from, and appreciate one another. It envisions that longstanding traditions of local crafts and arts as a winter evening activity can be “valuable for the project: There is a good chance that we can get Norwegians to offer their specific skills and abilities as teachers in Nyksund, either as part of the Nyksund Summer Academy or as a day programme.”51

Of these desires, ambitions, and plans – what we may call signals – some reached their intended recipients and resonated, while others fell to the ground. The divide between the young people of the INP was deep. The desires signalled by the protocol rekindles the need to revisit an interview we did with Grethe Andreassen in 2023. Being just 19 when she joined the INP, Grethe was hired to translate documents and thus bridge communications between Nyksund, the administration in Øksnes, and institutions across Europe. This role, her first experience beyond the bounds of her local community, brought a mixture of exhilaration and discomfort. Working with the INP was both thrilling and unsettling, leaving her with a profound sense of both connection and dislocation.

“It was like I was living in two separate worlds – one that was here in Nyksund. I felt at home, I felt safe, I felt cared for. I met a lot of nice people, although they looked totally different from me or anyone I knew at that time.”52

When she came back home for weekends, she encountered disinterest and fear in her local community. The stereotypes were hard to overcome. “Everybody” knew about the International Nyksund Project when Andreassen was hired as a communications manager in the early 1980s. Andreassen says her parents and friends had trouble relating to the international “world” that she was immersed in, in Nyksund. “They were just kind of shocked that I stayed here at all. Perhaps I was a bit strange too, they assumed.”53 The prevailing image that local youth had of their big-city peers was shaped by sensationalist stories from newspapers and TV about outcasts and drifters. To bridge this gap was a challenge.

50 “Ein Interkulturelles Zentrum für kreatives Arbeiten in Nyksund. Der interkulturelle Aspekt” (An Intercultural Centre for Creative Work in Nyksund. The Intercultural Aspect), p. 2. The paper is a treatment and part of the Ikea application for funding.

51 Ibid.

52 Grethe Andreassen, interviewed by NODES, August 2023, NBAA Archive.

53 Ibis

“Nyksund should not become a German exclave in the far north; internationalization was the goal from the very beginning.” The establishment of the International Nyksund Foundation was the prerequisite for this, with the Berlin group ensuring that the distribution of votes among foundation members meant that educational concepts could not be jeopardized by “other interests”. In addition to Øksnes municipality, the founding members included the association of homeowners in Nyksund and QuaBS e.V. Berlin, the Oslo-group and the Berlin association Nordlicht e.V., established by „friends“ of Nyksund (former participants). Internationality was not to be limited to the foundation countries of Norway, Germany, and Denmark. In fact, exchange programmes for six to nine nations were planned for the coming years.

Slide taken by Gunther Soukup, collection Renate Wendland-Soukup, 1985.

The students from West-Berlin regarded the INP as a contribution to active peace work. An international and intercultural mix was the goal for all the work camp phases. “Prejudices can only be overcome by direct confrontation and exchange with the ‘strangers’. Living next to each other is not sufficient and common tasks requiring communication and cooperation are necessary.”

Universities from Norway and West Berlin worked together on practical studies. 45 students from West Berlin and Bodø met in 1985 in Nyksund, welcomed by high-ranking community members who praised the incoming “new perspectives for the young people living in the region”.54 In mixed, interdisciplinary teams, they worked to repair houses, construct a solar shower, and build a greenhouse.55 For gardening and construction, materials found at place were recycled and reused.56

54 Final report, international meeting in Nyksund, 22 June–17 July 1985, p. 4.

55 The greenhouse included vegetable patches and compost heaps.

56 The reused materials included planks from the old bakery as well as shell limestone, peat, and sheep manure.

Slide taken by Gunther Soukup, collection Renate Wendland-Soukup, 1985.

“We all work together on the same thing, we are a close-knit community: Nyksunder.”57 The village community was international, intercultural, and multi-layered. The potential for conflict lies in groupings: “One of these groups is the ‘Studis’.58 […] The students set themselves apart, are spoiled intellectuals from well-protected, upper- and lower-middle-class backgrounds, and constantly have some kind of far-fetched ideas, too much sense of mission […].” The group composition had to be balanced, with no surplus of students or unemployed young people. “For this reason, we approached fewer students in 1987 than in 1986.”

The initial fears of contact were overcome in a playful manner: “Long live the Nyksund Rally! Multiple teams, discreetly mixed, well, and then, ‘Do you speak English?’ ‘Yes, a little...’.”59 What followed: curiosity, invitations to houses, conversations, listening to music, table tennis tournaments, delicious rømmegrøt, West Berlin on slides, the “Chaos Tour on the Klotind” and disco, dancing, celebrating together, falling in love, relationships, farewell tears. “In Nyksund, living together with others is much more intense. That is something that I found incredibly fascinating there. I’m probably like many people who were there. I’ll be there again.”60

57 “Der Traum vom Leben” (The Dream of Life), in: Broschüre 1986, p. 37. The text was written by Volker S., a student of Scandinavian studies, who worked as a translator.

58 “Studis” is short for students, “Teilis” is short for participants.

59 “Zwischenmenschliche Gepflogenheiten” (Interpersonal Customs), in: Broschüre 1986, p. 32.

60 “Gedanken zu Nyksund” (Thoughts on Nyksund), in: Broschüre 1986, p. 35.

Photos taken by Gunther Soukup, 1985. Funding of the International Nyksund Association. Around the table at Gunther Soukups apartment in Berlin, from to right: Willi Essmann, Anne Beate Hovind, Jarl Solberg, Gisela Brändl, Wolfgang Eschenhorn, unknown person, Mayor Finn Steen in suit and tie, unknown person, Volker Sommerfelt (red sweater).

Photos taken by Gunther Soukup, 1985. Funding of the International Nyksund Association. Around the table at Gunther Soukups apartment in Berlin, from to right: Willi Essmann, Anne Beate Hovind, Jarl Solberg, Gisela Brändl, Wolfgang Eschenhorn, unknown person, Mayor Finn Steen in suit and tie, unknown person, Volker Sommerfelt (red sweater).

The content of the box sparks the need to revisit another interview we did for our archive. Finn Steen, the former mayor of Øksnes municipality, is now a retired politician. Being fluent in German, he was instrumental in allowing the International Nyksund Project (INP) to establish itself in Nyksund. He speaks with fire about how the INP was, in fact, an incredible project – how they were unable to imagine the ripple effects it could have and the background it carried.

“In retrospect, it’s a mystery how we dared to embark on something so completely unknown to us. We only had a peripheral knowledge of the radical movements that existed in Europe at that time.”61

Steen, with his political interest, is today well informed about the political roots of the INP. He refers to Daniel Cohn-Bendit in France and Rudi Dutschke in Germany, noting that the “spiritual leader” of the Nyksund project, Gunther Soukup, was a close associate of Rudi Dutschke. Dutschke was a student leader and political activist, promoting a non-violent revolution of society from “within” – towards a society freed of capitalism and bureaucracy. Traditional families were to be replaced by new ways of living together.

61

Photos taken by Harald Sommer, 1988. Valborg Gamlesæther, a teacher, speaking German, invites participants of the INP into her garden for coffee and cake. Alongside Finn Steen, she was an important supporter of the Nyksund project.

Photos taken by Harald Sommer, 1988. Valborg Gamlesæther, a teacher, speaking German, invites participants of the INP into her garden for coffee and cake. Alongside Finn Steen, she was an important supporter of the Nyksund project.

Initially, Steen narrates, the Øksnes municipality had serious reservations about approving the project, concerned about its socio-pedagogical focus and worried that drug addicts might drain the municipality’s social welfare funds. The project led Steen and others to Berlin, where they met the youth who would be coming to Nyksund. There was a bit of a shock, he recalls. They regarded the young people they encountered as utterly rootless. “They had no home – not in the usual Norwegian sense, at least. That left a strong impression on us.”62

As the local leader of the organization created to support the INP, Steen took on the role of its primary advocate, enduring pushback from the community. Locals expressed fears about drug use and voiced concerns that echoed historical tensions. Steen’s impression was that some locals hadn’t quite finished with World War II yet. An illustrative reaction came after the participants of the INP had named the main street in Nyksund. A few locals harshly stated that they’d had enough of Germans out there. They insisted Steen and his fellow politicians made sure the street name was removed.

In regard to suspicions of drug use among the INP participants, the sentiment had a dramatic culmination in a razzia and subsequent negative press. A joint sent through the mail and addressed to one of the participants, confiscated at the local post office, led to a police raid involving dogs and a helicopter.63 The police found nothing, yet still “found it necessary” to report the incident to the local health authorities. The report concluded that the living conditions were unworthy and filthy: dirt, garbage, and messiness were everywhere. They deemed the conditions unfit for habitation, declaring it a health hazard. On the front page of Lofotposten, the bold headline read: “I would not have let my dog sleep there.”64

It was the beginning of the end.

62 Finn Steen, interviewed by NODES, August 2023, NBAA Archive.

63 Grethe Andreassen, En annen verden, Orkana Forlag, 2017.

64 Lofotposten, “Helserådleder stenger Nyksund-hus: - Ville ikke latt hunden sove der”, 17 October 1988.

Photo taken by Wolfgang Eschenhorn, House 65 dining and assembly room, 1987.

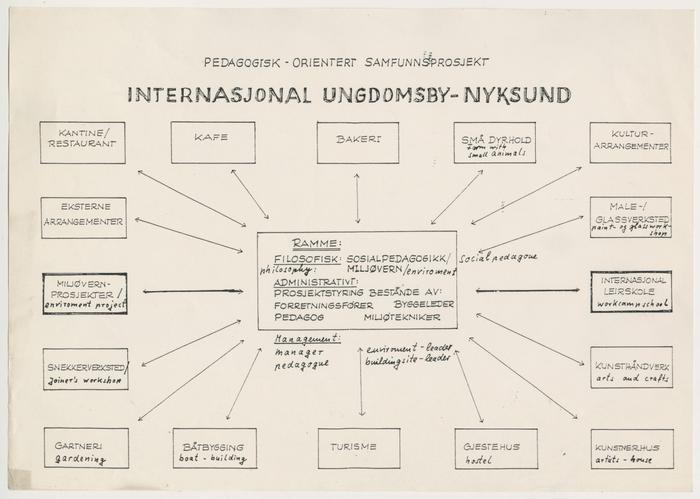

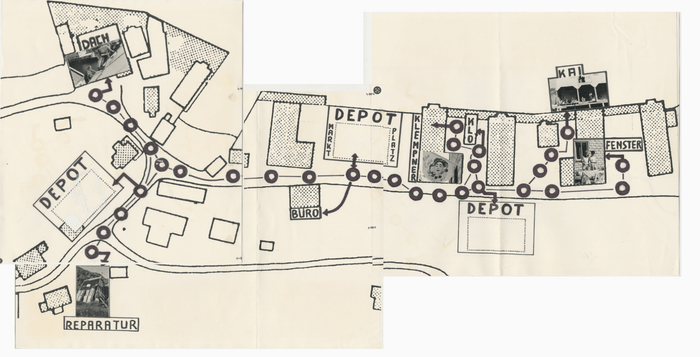

“The reconstruction of Nyksund with the help of young people is only possible with a functioning village community in which the participants feel comfortable. And for us this means that all participants must take responsibility for the functioning of village life.”65 The new village community set up a common space in House 65, which was both a dining room and the village assembly room. All met here on a daily basis in order to have a say in how the community was run. Weekly schedules of activities, lists of the building groups for which the participants could sign up, and a self-designed Nyksund map with cartographic symbols for the new village infrastructure hung on the walls.

“What constitutes the common good [Gemeinwohl] is a local cultural and social issue.”66 The new village was based on the values of the community (Gemeinwesen): solidarity, collaboration, responsibility, and participation. Co-participation and co-creation were not only possible in team and construction meetings, but also in self-managed areas, which, according to the 1987 summer programme, included the independent organization of the café, the guest house, and a kiosk.

65 “Nyksund Jahresprogramm” (Nyksund Annual Programme), 1987, p. 8, collection Götz Berge.

66 “Glossar zur Gemeinwohlorientierten Stadtentwicklung” (Glossary on Urban Development for the Common Good), chapter: “Common Good. Between Collective Needs and Individual Interests”, p. 70.

Diagram, The International Youth Village.

“Our project is strongly community-oriented: From the outset, we involved the people of Vesterålen in the project.” The locals met the new villagers at numerous activities outside and in Nyksund at schools, sports clubs, craft associations, the church, the disco, or concerts. Exchange trips to Berlin were organized. Two years after the project started, on 6 February 1986, the International Nyksund Association (Den internasjonale Nyksundstiftelsen, DINS) was founded with Øksnes municipality and the house owners´ association Gardeierforeningen as board members. DINS’s long-term goal was to establish an international youth education and meeting centre in Nyksund.

However, the interests of the homeowners who returned to Nyksund, attracted by the activities of the new inhabitants, may have had different concepts exploiting the village. For how else is the resolution of 12 August 1986 to be understood, “that the DINS Board does not wish the village to be used for tourist purposes or for businesses. Nyksund as an experimental field for research and education in practice should be protected from any commercial activities.”67 The board therefore calls for the non-profit principle: All revenues should be used for social purposes and for reconstruction. “We want the whole of Nyksund to be declared a profit-free zone. Commercial interests can have a negative impact on the pedagogical objectives.”

67 “Nyksund Jahresprogramm 1987” (Nyksund Annual Programme), p. 8, collection Götz Berge, p. 13.

The board of the Nyksund Game, developed by young people, 1987.

In a box, under contact sheets and brochures, in a blank envelope, there is an item: the Nyksund Game, developed by young people out of “frustration”. “The game development was in fact a method of processing their perceptions and evaluating them in a fun way,”68 explains Katja Beyer, who was involved in the INP as a student of pedagogy and educator travelling with a group of young people from Wilmersdorf, West-Berlin to Nyksund. The game board shows a map with buildings and sites used by the Nyksund project. Play spaces lead from the market square along the village’s main street to construction sites, as well as to the office and depots where tools are stored. Players have to pick a building site card from the five building areas and then set off in search of the tools they need to complete a task. A lack of materials and unsuitable tools, such as a jack to lift the quay superstructure, turns up as a Nyksund-specific problem, mentioned in student reports and the participants’ self-made brochures: “After the first inspection of the Old Bakery ruins, you go into battle for the first time for a spade, shovel, and hoe (only those who have been to Nyksund know how difficult this is).”69

As funding for “the big thing”, that is Nyksund as an International Youth Village, was lacking in 1986, the project remained stuck in Phase 1: repair and safety work on the “adventure playground”. Application documents justify the urgency for funding with the need to “create a visible, manifold success”. “A sense of achievement is the most important thing that previously unemployed young people can take home with them. A possibly still rainy Nyksund summer – without materials: That’s a nightmare.”70

68 E-mail from Katja Beyer to Katja Pratschke, student and educator at the INP, 23 October 2024.

69 “Arbeiten in Nyksund. Gammel Bakeri” (Working in Nyksund. Old Bakery), in: Broschüre 1986, written and designed by participants, educators, and teaching students after returning from Nyksund, at the Wannseeheim Berlin. Collection Wolfgang Eschenhorn.

70 Rainer Birkner and Stefanie Meyer, “Nyksund ‘86, zu Baumaßnahmen” (On Construction Measures), part of an application for funding from IKEA.

Photo taken by Wolfgang Eschenhorn, Roofing Work, 1987.

A protocol documented the expectations and misconceptions expressed by students, the Nyksund coordination team, and educators who all attended an evaluation meeting in Buchholz in 1987: complaints included overexertion, chaos, lack of competence, and overestimating oneself. A thesis paper on the future of Nyksund introduced into the discussions by Gunther Soukup proposed the end of Phase 1 (building conservation) and a switch to targeted construction. However, the transition did not only fail due to a lack of funding. The group was not successful in involving more Norwegians to the project, whether as team members, participants, or supporting institutions: “Without Norwegian commitment, there will be no targeted construction planning, no funding, and no internationality in Nyksund.” Many voices can be heard in the protocol as possible scenarios are played out. There is mention of shutting down the project and a responsible departure. Soukup “sees us as being responsible for Nyksund and advocates a gentle exit, taking social aspects into account; we should develop a community [Gemeinwesen] concept. He proposes an evaluation of Nyksund under the aspect of ‘the Nyksund project and its significance for today’s theories on youth’.”71

71

Collage and animation by Iryna Kliui and Katja Pratschke.

The International Nyksund Project ended in 1992, three years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Burkhard Herrmann led the Nyksund project until 1989, when it was handed over to Norwegian management. Herrmann took on the challenge of reuniting East and West German youth through a new project located on the inner German border. As early as 1987, Gunther Soukup recognized the need to evaluate the Nyksund project: “The project must be ‘worth’ a lot in itself, as it increases the labour market value of those involved in the project.”72

This “worth” is what we aim to reflect on, retransmit, and re-actualize. We would not be “accidental archivists”73 if we did not recognize a “value” in the INP’s scattered legacy. Our position is that this value should be collected, preserved, spread, and developed – or rather, re-transmitted. Therefore, we have established what we call the Nyksund Berlin Artistic Archive (NBAA), making the material accessible for future users. Here, the INP serves as the starting point for future artistic research projects focused on present and future challenges. The NBAA is an archive of the practical experiments, successes, and failures of the INP that future users – activists, artists, researchers, students, young people, and the community – can adopt or avoid. In many ways, our motivations align with what Hal Foster calls an an-archival impulse: the artistic need to establish new beginnings and new points of departure from incomplete or unfulfilled projects of the past rather than to seek absolute origins.74

What we have established is a database – a concept for the structure, starting with making only parts of the image material accessible. The first records have already been published in the NBAA. We have to stress – re-transmitting signals is a considerable amount of work. Archiving is a challenge; it is overwhelming and time-consuming. We are still at the very beginning, as Wolfgang Eschenhorn, now supporting us, has noted. Eschenhorn, who travelled to Nyksund as a member of QuaBS and an educator with teenagers from Neukölln between 1986 and 1989, contributed his material – negatives, brochures, and documents – to the NBAA. Eschenhorn has become a collaborator.

The material scanned and uploaded to our digital archive reconnects us with the donors, former students, educators, participants, and organizations who help us grasp the complexity of the International Nyksund Project in depth.

We are now looking for future “helpful users” to join us with their research interests and their desire to develop tools that enable diverse access to the material. As accidental archivists, we approach the archive not as a static repository but as a dynamic field of possibilities. We present the archival fragments not as definitive conclusions but as materials charged with utopian desires, ready to be recontextualized and revitalized.

72 Gunther Soukup on his interests in the Nyksund project, in the protocol of the closed-door meeting 1987 in Buchholz, West Germany, p. 19.

73 Didi Cheeka, “Accidental Archivism: A Necessary Accident”, in Accidental Archivism, Meson Press, 2023.

74 H. Foster, “An Archival Impulse”, October vol. 110 (Autumn 2004).

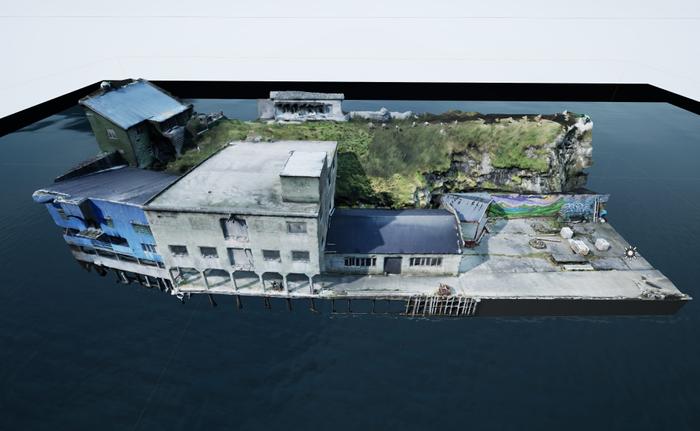

VR, The Freezer, 2024. 3D Scanning & Photogrammetry: Ivar Kjellmo.

The building of the Freezer (Fryseriet) is becoming an arena for picking up and transmitting the INP’s utopian desires. We pick up the attitude of experimentation, interdisciplinary knowledge exchange, and community building. We adopt a method of working: diverting attention from individual contributions to collective efforts. We are jointly creating a digital space – a place for artistically and scholarly experimenting with the INP’s archival material.

In a workshop in Nyksund in 2023, we – a group of six media artists, artistic researchers, media researchers, filmmakers, sound artists, and 3D artists – collectively create a mesh of images, of 18,000 photographs recording every detail of this building and its content, inside and out, and feed them into photogrammetry software. We agree not to touch or move anything, preserving the building and its archival “mess” in time, recording traces of artistic and economic activity as they appear in August 2023. The result is a digital model – a highly detailed 3D space that contains the potential for interaction, immersion, and experiences that can connect users to the archival material, the place of Nyksund, and the INP’s utopian desires.

VR, The Freezer, entrance Fileten, 2024. 3D Scanning & Photogrammetry: Ivar Kjellmo.

The digitization of the Freezer preserves its open and free quality. For decades, the space has been one of the last areas untouched by profit-oriented tourism. Questions about how this place could survive in today’s market-liberal economy have long preoccupied the local community. Meanwhile, the Freezer has remained a space of possibility for artistic experimentation, offering a unique quality of roughness – an atmosphere, perhaps an aura. Objects and machines from fish processing, chairs and technical equipment from exhibitions, traces of artistic experimentation with graffiti are all scattered throughout. Birds’ nests – colonies of seagulls, krykkje, have taken over its front. Feathers cover the concrete floor, and moss grows in the cracks. The building is an empty shell, yet it is charged with signals from different time periods. Ecologies of humans, animals, and plants intersect and coexist. The building is charged with the desire for modernization, for freedom, for co-creation, for play.

The processing stations in the multi-storey building – from the machine room to the filleting area, the storage, the cold room, and the elevator leading to the roof – and the processes that took place there, the filleting, freezing, packaging, and shipping, are understood by us as model stages of processing the archive. As a VR experience in a game engine, the model allows users to enter and explore the building virtually and independently of physical location, with an avatar to facilitate interaction and engagement. Immersion into the archive is made possible through artistic projects exhibited in the virtual space, through curation and gaming.

VR, The Freezer, first floor, 2024. 3D Scanning & Photogrammetry: Ivar Kjellmo.

The INP material encompasses diverse voices and perspectives. It contains signals addressing urgent contemporary issues and calls for action. How can we design an immersive, interactive framework that does not restrict interaction but instead fosters participation, co-creation, and experimentation to discover answers and solutions?

In August 2024, we exhibited an initial 3D model as a VR experience for the locals in Nyksund and beyond. During the biannual Norwegian Storytelling Festival (Fortellerfestivalen), we set up a VR experience in the Freezer, inviting the local public to participate. The interest was significant among both young and old. People described the experience as thrilling, exciting, and somewhat unsettling, and it was clear that they were curious and enthusiastic about the kind of modern “story” we could present.

VR experience The House of Broken Utopias, LIAF 2024, Nodes Collective, photos by Gusztáv Hámos.

VR experience The House of Broken Utopias, LIAF 2024, Nodes Collective, photos by Gusztáv Hámos.

VR experience The House of Broken Utopias, LIAF 2024, Nodes Collective, photos by Gusztáv Hámos.

The INP was particularly targeted toward the young – what at the time was the generation of future European grown-ups – tasked with ensuring a sustainable and peaceful co-existence in a time of nuclear threat and worries about the ozone layer. The archival material in our hands radiates with desires for better futures. What could these better futures look like in today’s world, which is characterized by fears of loss, exploitation, acceleration, ecological destruction, climate catastrophes, and rising authoritarianism?

The INP motivated young people to realize their potential through self-determined action, direct and embodied experiences, and the assumption of personal responsibility. The focus was not on the so-called “deficiencies” of young people but on their interests, from which skills could, in turn, be developed: “The aim was not to convey desperation, powerlessness, and a flight into resignation but rather to enable success despite everything.”75 For the INP, Nyksund was not only a shapable space, but also a social space with people who cared for each other: “The desire for social recognition, the desire to be loved, respected and valued” is what really motivates people to make a difference, to change, as the sociologist Hartmut Rosa put it.76

These signals – the young people’s desires for “social recognition”, the desire to be seen, respected, taken seriously, and considered – are picked up by our collective NODES. Through our Nyksund Berlin Artistic Archive (NBAA), we retransmit these signals, striving also to build a sense of community: a starting point for encounters, discussions, research, and projects. Leveraging the opportunities offered by digital technology, our archive will move, connect, immerse, expand and become a physical place of interaction, encouragement, and solidarity for projects and actions by and for young people.

75 Götz Berge, “TPS: Konzeption, Planung und Organisation. Was ist ein Projekt?” (Concept, Planning and Organization. What is a Project?), in: QuaBS e.V. Nyksund-Auswertung (Nyksund Evaluation), Ka p. C, unpublished.

76 “Acceleration and Resonance: An Interview with Hartmut Rosa”, interviewed by Bjørn Schiermer, https://journals.sagepub.com/pb-assets/cmscontent/ASJ/Acceleration_and_Resonance.pdf

In this sense, the search for the “third common cause”, on which project success depends, as often mentioned by Burkhard and Wolfgang, can also be explained: “The problems should be exemplary: for current/future practice; for current conflicts in the social system, for intervention strategies of society, for the creation of alternatives. The third common cause makes it possible to be prepared to give up one’s habits, one’s current state, for the sake of this common cause.”77

What emerges through our collaborations of today, then, is a new Nyksund project – a digital, virtual, physical space, an experience that touches and concerns us today, to which we may react and respond. It is a place for collective, collaborative, and co-productive encounters. “An experience of resonance – with a person, an idea, a landscape, a village – we come out as a different person. And the other side is transformed as well.”78

77 Götz Berge, “TPS: Konzeption, Planung und Organisation. Was ist ein Projekt?” (Concept, Planning and Organization. What is a Project?), in: QuaBS e.V. Nyksund-Auswertung (Nyksund Evaluation), Ka p. C, unpublished.

78 “Acceleration and Resonance: An Interview with Hartmut Rosa”, interviewed by Bjørn Schiermer, https://journals.sagepub.com/pb-assets/cmscontent/ASJ/Acceleration_and_Resonance.pdf

The essay shifts between the history contained in the documents, descriptions of the documents and their condition today, this projected, ongoing archival project, and the authors own relation to and memories of the places they write about.

- Alena Rieger

It jumps back and forth, it travels! For me, I think the questions and awareness on how curatorial power in archives, as well as outside the archive, inspirers and relates, as it holds deep consequences for the once involved. How to label, structure and make sense of fragments, what happens when they are put together in certain constellations, how can it be changed.

- Gyrid Øyen